CEO Succession Study “We should have started earlier”

Chairmen and CEOs share best practices and challenges in preparing for a change at the top

Everyone agrees that CEO succession planning is critical, particularly as leadership changes become more frequent. Yet many Chairmen are concerned that their own companies are underprepared for a change of CEO – and are exposed to the risk of a damaging leadership vacuum.

This is the finding of a recent Egon Zehnder study in which more than 50 Chairmen and CEOs of major companies headquartered in France, Germany, the UK, and the US were interviewed. The study shines a light both on best practices in CEO succession planning, and on the greatest gaps. It shows that several common “roadblocks” stand in the way of seamless succession plan- ning, and draws on the participating leaders’ own experience and advice on how to overcome those blocks.

CEO succession planning today – the best and worst of worlds

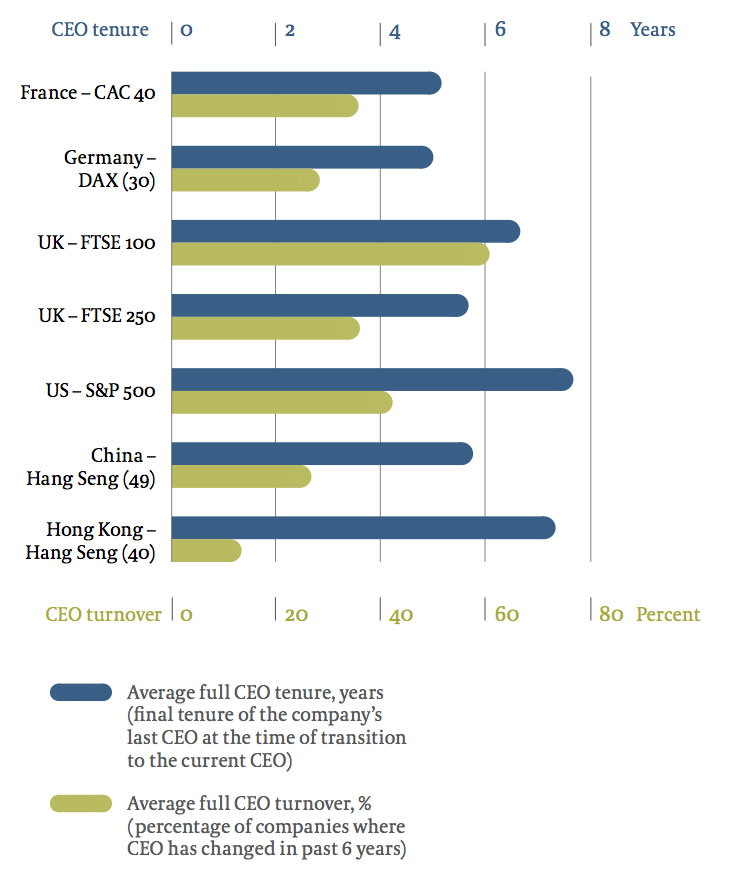

Today more than ever, CEO succession planning matters. CEOs who stay in the role until retirement are now very much the exception, as research by Egon Zehnder shows. In some countries, CEOs of listed companies have average tenures of just five years. Given the high rate of CEO turnover, Chairmen can expect to oversee a CEO transition during their own tenures – on the FTSE 100, for example, more than 60% of companies have changed CEO in the past six years.

CEO tenure and turnover for global indices as per stock indices as of October 2012

In this context, the findings of our CEO succession study are cause for concern. Many of the leaders interviewed felt that CEO succession planning in their own companies lacked rigor, and several pointed to sub-optimal CEO succession experiences of their own. The words of one Chairman, experiencing a current CEO succession challenge, underlined a gap that is all too common:

“We didn’t start planning until the CEO announced his intention to retire. Now, there is barely enough time to go through a thoughtful process. We should have started earlier.”

In companies that had not recently changed CEO, many Chairmen were just as concerned about the robustness of their succession planning. Some had never overseen a CEOtransition, and said this lack of experience made it difficult to assess their company’s succession plans with confidence.

But the picture is not all grim. In some companies, CEOsuccession planning is a well-honed science, ingrained in the culture and in the organization’s leadership processes. As one Chairman told us: “Succession planning has been normal behavior in the more than 100 years of this company’s existence.” Another said:

“It is in the genes of the company to prepare for CEO succession. The process starts early and it really begins with diversity at the top 50 level and with preparation for roles on the Executive Committee.”

Such leaders agreed that the defining characteristic of good succession planning is that it is “always switched on” – the planning process ensures that a company is constantly prepared for a leadership change, expected or unexpected. This not only reduces risk, but also contributes to a greater frankness and alignment between the Board and the CEO.

In conversation with study participants, we disaggregated good CEO succession planning into six best practices:

1/ Clear role specification for the CEO, informed by the Board and detailing the experiences and competencies required to lead the company”.

2/ Regular assessment of the CEO, against both the role specification and his or her performance.

3/ Active development of internal bench strength, with potential CEO candidates identified, assessed, developed, and benchmarked against the best external leadership talent.

4/ External scans of potential CEO candidates from the market, supported by global search consultants.

5/ A robust CEO integration process to help ensure the incoming leader’s success.

6/ Emergency planning to cater for a sudden, unexpected CEO departure.

Although there is broad agreement on the value of these practices, only a minority of companies fully apply them today. And while the country context differs, significant gaps remain across all markets. Even companies with advanced succession planning processes often have room for improvement in one or more practices.

Positive CEO succession experiences …

“I became CEO in 1999, and the first discussion about succession happened the following year. Twice a year, the Board does a talent assessment and succession planning with the Board, of all top 50 positions and 40 potentials in the pipeline. The candidates are ranked across all aspects and characteristics. The senior leadership has a good rapport with the Board. Succession is an active process.” “In planning my own succession as CEO, I had an excellent experience. I had an experienced chairman who never second-guessed me – this relationship was central to our success.”

… and negative

“We had no plan – it was entirely opportunistic.” “The Board thought it had three candidates: then one had to be fired, one didn’t have the fire in his belly, and one left. All cover evaporated.” “In my case it was the worst practice ever. They shot both the CEO and the Chairman at once, with no Plan B.” “We didn’t start planning until the CEO announced his intention to retire. Now, there is barely enough time to go through a thoughtful process. We should have started earlier.”

The country context

The study highlighted a few important differences in CEOsuccession planning across the four countries surveyed:

- Germany’s unique governance system makes it more likely that the Chairman personally drives the CEOsuccession effort. France, the UK, and the US tend to see broader involvement from the Board.

- Governance models with greater separation of executive and non-executive authority – such as in the UK – tend to have more comprehensive CEO succession planning processes and greater openness to explore external options and use external advisors.

- Sensitivities about how to plan for succession are higher where the incumbent CEO has responsibility for overseeing the process – often the case in unitary governance models such as in France and the US.

SIX roadblocks to applying best practice – and how to overcome them

What stands in the way of broader adoption of best practice CEO succession planning? The study highlights several common issues:

- Many companies struggle to conduct robust CEOassessments, because Boards are often uncomfortable discussing the CEO’s performance.

- The development of internal candidates for CEOsuccession is often hampered by the fear of starting a competitive “race” inside the leadership team.

- The practice of benchmarking internal candidates against the market is often resisted because even consideration of external candidates is sometimes seen as a risk to the company’s strategy, or as an admission of failure.

- Formal CEO integration processes are widely seen as unnecessary – new CEOs are expected to “have what it takes” to succeed on their own.

Just as serious a challenge lies in the fact that companies often apply CEO succession practices in a watered-down way. For example, many of those that assess their CEOs do so in an informal rather than a structured way – giving the Board an incomplete picture of the CEO’s performance, and the CEOfewer insights for growth. Likewise, detailed CEOspecification is often passed over in favor of broad role descriptions, particularly when the focus is on internal candidates. In this case an attitude of “we know them” gets in the way of considering “what they could be” – a question which a robust specification helps answer.

We distilled these challenges into six common roadblocks to activating best practice. And, drawing on the best of the CEOsuccession processes already in place in participating companies, we gathered leaders’ advice on how to overcome each roadblock.

Roadblock 1/ CEOs control their own succession

Many Boards do not exercise control over the CEO’s departure date and typically leave this to the CEO to determine – or they accept a fixed retirement date that could be as many as 20 years away. Indeed, one-third of the CEOs we interviewed in France, Germany, and the US had not discussed the possible timeframe of their own succession with the Board.

The leaders interviewed had clear advice on how to overcome this roadblock. Several companies have put in place committees to manage CEO succession, often with a senior independent director in the leadership role. Best-practice Boards also engage with the CEO on his or her future career intentions, in the context of regular feedback sessions. One Chairman recommended that such discussion take place annually from the outset of a new CEO’s tenure, to avoid surprises down the line.

Finally, several of the CEOs interviewed emphasized how important it was for them to be open to discussions about their own succession. Said one:

“Don’t think you are irreplaceable, because you are not. It’s much better to be asked ‘why are you going?’ than to be asked ‘when will you go?’”

Roadblock 2/ No real plan for unexpected leadership changes

Only a minority of companies have plans in place to cater for emergency leadership changes, and even fewer plan for nonemergency but unexpected CEO changes over a 2-5 year horizon. This is cause for real concern, given the short average CEO tenures cited above – and the fact that around one in three CEO successions are unplanned.

Of those companies that do have emergency plans, several concede that these amount to little more than “box-ticking” to comply with regulatory requirements; in the US, for example, a ruling by the US Securities and Exchange Commission makes CEO succession plans obligatory.

The advice from interviewees is that companies need to have a plan for all possible scenarios of CEO succession. These plans should be based on active Board discussion on the future needs of the company, and on the leadership competencies and experience required to meet those needs. Further, Boards should regularly assess and provide feedback to the current CEO.

For some companies, a key aspect of emergency planning is to prepare the Chairmen to step into the CEO role. As one leader said:

“The Chairman’s role specification should ensure that he or she has the skills, experience, and time to step into an interim CEO role if needed.”

Roadblock 3/ Reluctance to plan for CEO succession “too soon”

For many Boards, it can seem awkward – and unnecessary – to begin planning for a CEO’s succession soon after he or she is appointed. But interviewees from best practice companies were adamant that you can never start too soon. As one Chairman said: “As soon as a company appoints a new CEOthey should start planning for his or her successor. You always need a game plan.” Another Chairman issued a warning:

“Start on Day 1: often the cupboard is bare as you lose the unsuccessful internal candidate(s) and/or you promote the only one. Be realistic: it takes years to develop future CEOs and get them ready.”

Several companies reported that annual evaluations of CEOsuccession potential were established practice in their Boards. Such companies typically make the development of a strong “bench” of potential CEO successors a critical priority for both the Chairman and CEO. Indeed, a number of Chairmen noted that they personally invested significant time in getting to know these next-generation leaders, and in making them visible to shareholders. At the same time, the development of internal successors is written into many CEOs’ key performance indicators.

Roadblock 4/ Refusal to consider external candidates

Most companies – the study participants included – would prefer to hire their next CEO internally. Some, however, are adamant that they would not even consider hiring an outsider, and that this would be tantamount to failure by the Chairman and Board. One Chairman interviewed said: “A lack of adequate internal potential would be a disaster and a very bad omen for the company.” Echoing this sentiment, a CEOsaid: “If I do not succeed in producing a minimum of two good internal candidates, I will have missed something extremely important.”

Several best-practice companies had a more nuanced approach, and counselled on the value of being able to compare across, and select from, a slate of both internal and external candidates. One Chairman said: “The CEO has to be the best – and you must have options.” A number of interviewees emphasized that external mapping of the leadership talent market creates competitive value, as it reveals what type of talent has driven business success elsewhere. Looking externally can also be valuable from a governance perspective, as another interviewee recounted:

“We had a strong preference for an internal successor, but the Board called for assessment of external options to ensure proper due diligence and governance of the decision.”

Roadblock 5/ Fear that CEO succession could become “too transparent”

CEO succession is a sensitive topic. Indeed, many of the leaders interviewed were concerned that greater transparency in succession planning could be destabilizing. As one Chairman said: “I see a reluctance in Boards to raise the succession issue in case the CEO sees it in the wrong light and starts to look outside.” Several interviewees expressed misgivings about Boards formally assessing CEOs, fearing that this might be seen as micromanagement or a challenge to the CEO’s suitability.

Other interviewees were concerned about the effect of making it known that internal candidates are being considered as potential future CEOs. Said one: “We don’t want to go official about the successors – we don’t want to create crown princes.” A CEO set out his own approach in this way:

“Total transparency to the two successors, but invisible to everyone else. If people were to start thinking that I’m about to leave, they might stop listening to me.”

But there were also strong arguments in favor of transparency. Some study participants advocated depersonalizing CEO succession planning to mitigate sensitivities, presenting it as a broader talent identification and development planning exercise. Several also emphasized the value of Boards conducting robust CEO assessments: “CEOs see feedback as important in doing well in the role,” said one. “Things get ugly when the Board is surprised, and an assessment process can prevent this,” said another. One CEO vociferously defended transparency, saying:

“Strong CEOs are not insecure and understand that being a CEO is a privilege rather than a right. They worry about their personal succession as much as the Board does.”

Finally, interviewees stressed the importance of managing internal candidates’ expectations and openly discussing the choice criteria – an approach which helps unsuccessful candidates understand the Board’s decision and stay with the company.

Roadblock 6/ Integration support for new CEOs seen as unnecessary

Integration – the last step of a CEO transition – is often forgotten, and even seen as unnecessary. “There’s no need – the CEO has to swim by himself,” was a common view amongst interviewees, especially in Germany, where a CEO’s prior career in the company was often seen as sufficient preparation.

Nonetheless, several study participants emphasized the value of investing in integration support for an incoming CEO, whether he or she is an internal or an external recruit. “Giving the new CEO unequivocal and full support means you get alignment and there is no second-guessing about what’s going on,” said one Chairman. Another spoke of the problems experienced by a recent CEO appointee who had not been offered such support:

“The CEO had little preparation to step up his role. In hindsight, integration could have helped. He is still somewhat tentative in certain aspects of the role, and rather more defensive with respect to the Board than he should be.”

Study participants put forward several key steps for integration, including offering the new CEO early, focused advice on the functioning of the Board; ensuring he or she receives regular, structured feedback from the Chairman; and giving him or her guidance on building stakeholder relationships inside and outside the company.

In sum, the study makes it clear that the dangers of insufficient planning for CEO succession are real and significant. It leaves no doubt that most companies have room for improvement – and shows that those applying good practice not only reduce the risk of a leadership vacuum, but can also strengthen governance, CEOperformance, and senior leadership bench strength.

Across major markets, Chairmen and Boards are asking: “How robust is our CEO succession plan?” Many have not yet seen their succession processes tested by actual CEO transitions – and are anxious to avoid discovering gaps when it is too late to fix them. Perhaps the greatest value the study presents to Chairmen and Boards is the opportunity to learn from their peers’ experiences, before making a costly mistake of their own.