2016 Egon Zehnder Latin American Board Diversity Analysis

Introduction: Gender diversity on the global agenda

Across the globe, gender diversity has been on the agenda of boards and nominating committees for more than two decades. As Latin America becomes an increasingly important part of the global economy, investors, corporate governance experts and other observers are beginning to examine the region’s companies against global norms. As a result of these developments, it is important for Latin America’s boards and CEOs – regardless of the level of priority they personally place on gender diversity – to have a clear understanding of the state of boardroom gender diversity in their country and region. The 2016 Egon Zehnder Latin American Board Diversity Analysis provides a snapshot of gender diversity among leading publicly traded companies from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico1, and proposes recommendations to help increase gender diversity in Latin American boardrooms.

Establishing a baseline

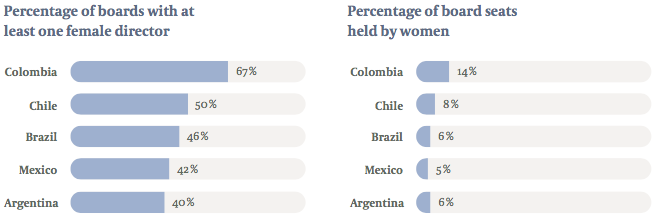

To assess the current state of boardroom gender diversity, we analyzed the board composition of 155 public companies headquartered in the five selected countries that had a market capitalization of US$1 billion or more.2

At the country level (Figure 1), one can see the role played by culture and politics by examining either end of the spectrum. In the early 1980s, Colombia began establishing greater equality for women in politics when its president, Belisario Betancur, appointed women to all vice-ministerial positions. (Eventually, women were appointed to three ministerial roles.) This established the beginnings of a pipeline of women who had developed their boardroom credentials though governmental positions of high visibility and responsibility. This pipeline was further strengthened in 2000, with the establishment of quotas mandating that women account for 30 percent of all senior government positions at the national and regional level. The results of these developments can be seen today in the relatively high levels of gender diversity in Colombian boardrooms. Colombia also has a higher percentage of single-parent households compared to other Latin American countries in the study (84 percent versus the regional average of 65 percent3), suggesting a culture in which the economic independence of women has been more strongly established.

Argentina, by contrast, has in recent years suffered from high inflation and has imposed trade regulations and exchange rates that have deterred foreign investment. Numerous multinational corporations have left the country, and those that remain are necessarily focused on short-term profitability rather than establishing corporate governance best practices. In addition, Argentina’s capital markets have become less accessible and smaller in size, removing another potential force for encouraging adherence to global boardroom norms.

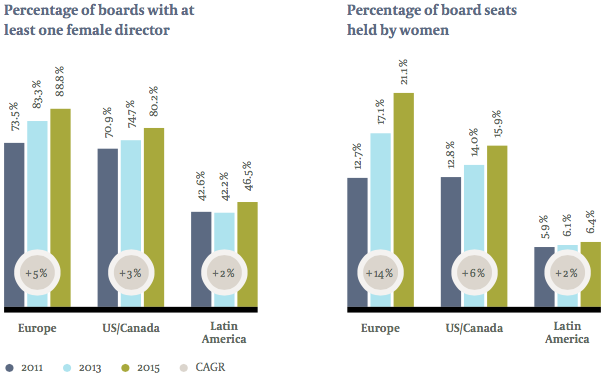

When comparing these five Latin American countries as a group with Europe and the United States and Canada (Figure 2), we see that Latin America lags behind the other two regions, both in terms of actual percentages of women’s participation and in the rate of annual increase.4 However, the rate of change in Latin America, while lower than elsewhere, is still positive, which suggests that the idea of gender diversity in the boardroom may be gaining some traction.

Accelerating the rate of change is important because of how much Latin America will fall behind other regions if no action is taken. To put this in perspective: North American and European business leaders are increasingly supporting a near-term goal of having women account for 30 percent of board seats. By our calculations, at the current rate of change,5 Europe will reach that goal in 2018, North America in 2021 – and Latin America in 2042, a generation from now. It is our belief that this gap will put Latin American boards at a significant disadvantage in helping their companies compete in a world in which women represent half (or more) of the purchasing power and a growing share of the talent pool.

Board members’ beliefs and experiences regarding gender diversity

Gender diversity in the boardroom is a complex issue, involving the role of women in society, at home and in the business world; the procedures and policies of nominating committees; the extent to which boards are independent; and where gender diversity fits among other issues competing for a board’s attention. Statistics can therefore tell only part of the story. Confidential interviews of 33 board chairs – all but four of whom were men – and interviews with 28 additional female board members, from a total of 61 companies, provided essential nuance and background. From those discussions, which took place between August and November 2015, we can make the following observations:

There is no consensus on the importance of having women in the boardroom

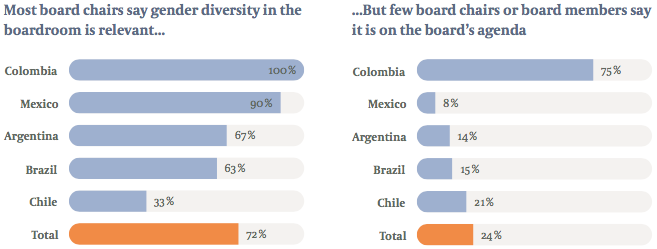

More than two-thirds of the board chairs interviewed said that having women on boards is relevant for a board’s performance. But our discussions suggested that support may be lukewarm. Only 24 percent of the board chairs and board members we surveyed – and only 15 percent of those not on Colombian boards – consider increasing gender diversity to be on their board’s agenda (see Figure 3).

“Having women is a contribution, but it is not a matter of life and death.” - Board chair, Chile

“Yes, I do think [having female board members] is relevant, although many chairmen do not believe this.” - Female board member, Colombia

“First, we should solve the base of the pyramid: institutionalism, growth, financial markets in Argentina. After that we can talk about gender and corporate governance.” - Board chair, Argentina

The chairs and board members who do value diversity do so for pragmatic rather than philosophical reasons: to bring a broader set of perspectives into board discussions, to better draw from the pool of talent or to better reflect the company’s customer base.

“Diversity is relevant for us because our main clients are women – they are the ones who decide whether or not to purchase our products. And only if we include more women in the workforce will we be able to grow as a country. We are currently ignoring talent.” - Board chair, Chile

“Women always have a different business perspective, and it is essential to bring different perspectives and backgrounds to board discussions and help companies be more innovative and thereby improve their financial performance.” - Female board member, Mexico

We also observed an important generational divide, with younger chairmen and board members hewing to a distinctly meritocratic worldview:

“We believe in equality of opportunities, without positive or negative discrimination. It is merit that matters. We seek people with expertise in the industry, with proven results, and that are trusted by the controllers.” Young board chair, Argentina

“Diversity is not relevant. We look for people who can contribute, regardless of their sex, race or color. We look for different perspectives.” - Young board chair, Chile

Whether this results in greater gender diversity remains to be seen.

Boardroom gender diversity is one component of the larger corporate governance environment

Boards without a significant percentage of independent directors have less latitude to shape their composition.

“The way in which Mexican shareholding participation is defined generates a challenge for gender diversity on the board.” - Board chair, Mexico

“It is hard to develop good corporate governance with strong controllers like those in Latin America. Board evaluation becomes an attack on the controller. The concept of an independent board member helps.” - Female board member, Colombia

But companies actively looking to attract foreign capital place greater priority on conforming to global expectations – one of which is to have a diverse board.

“By wanting to be part of the OECD and to have foreign shareholders, diversity becomes part of the discussion, but it is still a concept that comes from abroad.” - Female board member, Colombia

“Argentina has been closed to [foreign] markets, and the spillover of good practices from the US and the EU has not reached here.” - Female board member, Argentina

Boards are largely self-perpetuating

New members are drawn from the personal and professional networks of current members. This leads to a predictable level of homogeneity not only regarding gender but nationality, educational affiliation and other attributes.

“The biggest problem is the Chilean mentality that you distribute the cake rather than increase its size. [The board] is a closed circle of friends—not against women, but in favor of trusted friends.” - Female board member, Chile

“Boards in Latin America are still formed by groups of friends. Women are only considered when they are related to one of the shareholders or if there is an executive search firm involved in the process.” - Female board member, Brazil

Women often face cultural biases regarding their leadership ability

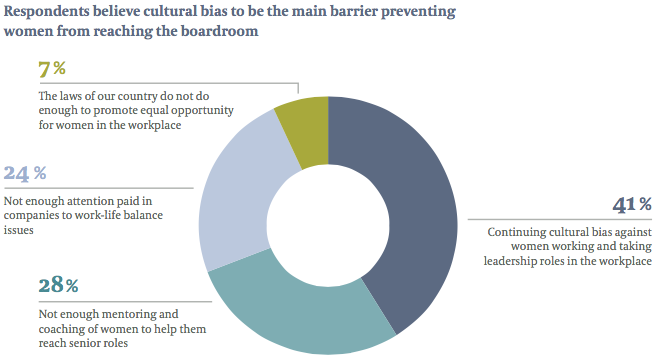

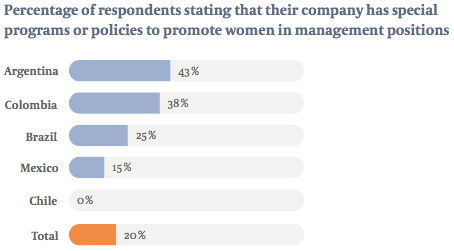

In many places, traditional biases have created hurdles preventing more women from reaching corporate leadership positions. Forty-one percent of the board chairs and board members we interviewed said that “continuing cultural bias” was the largest impediment for women reaching board positions (see Figure 4). Further, most companies have yet to take concrete action regarding this; only 21 percent of the board chairs and board members interviewed said their company has special policies or programs to select, hire and promote women within management (see Figure 5).

This situation was echoed in our interviews:

“In general, female candidates have to show greater credentials than their male counterparts.” - Female board member, Mexico

“We women are promoted based on results, while men are promoted based on potential. Women have to show before they get promoted.” - Female board member, Chile

“To get to the boardroom women need to proactively search for more exposure and to demonstrate their potential in every single interaction.” - Female board member, Brazil

Not surprisingly, in this environment many chairmen believe that there are few if any women qualified to sit on boards:

“We looked for a female board member in the past, and we did not find one. So we dropped the subject and it is not a topic on our agenda anymore.” - Board chair, Brazil

“We don’t have enough female executives with the necessary experience to become a board member. This is the greatest challenge.” - Board chair, Mexico

Female directors in particular feel this perspective has caused the qualified women that do exist to be overlooked:

“First, we need to get past this idea that there are no women. Maybe there are not enough to reach 50 percent representation in the boardroom, but there are enough for 10 or 15 percent!” - Female board member, Chile

Strengthening the pipeline of female directors requires addressing complex work-life issues

In Latin America as elsewhere, nominating committees place a priority on recruiting independent directors who are already sitting on a board or are retired CEOs or, at a minimum, have a track record of substantial P&L responsibility. The challenge of establishing an adequate pool of women who meet these criteria is not restricted to Latin America – it is an issue that affects all regions. Addressing this will require solving complex problems regarding work-life balance and conventions regarding household responsibilities.

“Most companies in Argentina have a 24/7, owner mentality. It is not possible [in these conditions] to handle both work and family.” - Board chair, Argentina

“It is harder for women to advance in their executive careers due to the family responsibilities, so they do not reach the senior roles and do not ascend to boards. Things have to change culturally and at home.” - Female board member, Brazil

“A larger proportion of women work in support functions, and those roles generally do not give you the operational experience needed to become CEO and therefore be eligible to become a board member.” - Female board member, Mexico

Importantly, there does seem to be consensus that these larger societal issues need to be addressed:

“Companies should transform and become ‘family-responsible’ organizations. [At our company,] we are designing policies and procedures to allow women and men to balance their interests and responsibilities and therefore allow them to grow professionally.” - Board chair, Mexico

“We need to talk about this as a society; we need to measure diversity and publicize the results. We need to tell businessmen, ‘The winning company is the one that includes women. This is a matter of competition, not of fairness.’” Board chair, Chile

There is significant opposition to gender-based quotas

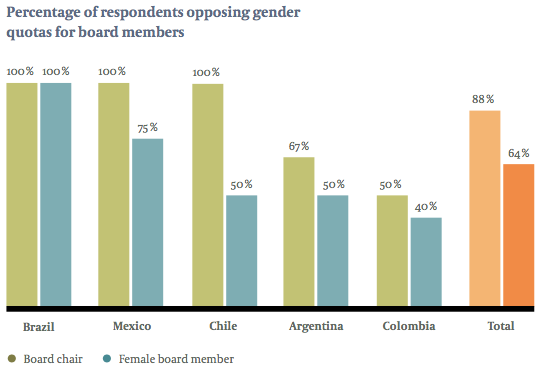

Several European countries have used government-imposed quotas to move boards toward gender parity, but that approach is widely rejected by board members in Latin America, where the preference is toward voluntary – if any – targets.

“I am thinking that the next director should be a woman, but I am not talking about it because I do not want it to be seen as a requirement. Quotas demean women.” - Board chair, Chile

“I do not like quotas. I hope that naturally and smoothly society will change and see the value of it.” - Female Board member, Brazil

“I am against quotas. Decisions should be based on talent.” - Board chair, Mexico

While almost 90 percent of the board chairs interviewed opposed quotas, female board members were only moderately more open to them, with 64 percent of them saying they are not the solution (see Figure 6).

“Quotas are incredibly humiliating.” - Female board member, Chile

“Equality is increasing in our culture, but there is still a long way to go. The government and companies must broaden their inclusion policies. I’d rather not have quotas, but if that’s the way to move the needle, let’s start from there.” - Female board member, Argentina

Conclusion and recommendations

There is clearly much to be done to achieve greater gender diversity in Latin American boardrooms. The quantitative differences between Latin America and Europe, the United States and Canada are stark – but one must also take the element of time into account. In the United States, for example, 30 years ago it was common for board chairmen to explain all-male boards with a lack of qualified women (as often happens today in Latin America); 20 years ago, the increasing number of women in governmental (and not-for-profit and educational) leadership positions strengthened the pipeline of female corporate board member candidates (as it did in Colombia); today, corporate leaders in the United States, like those elsewhere in the world, are grappling with the need to increase the number of women in P&L leadership positions and to address complex issues of work-life balance. It thus is more constructive to think of a common gender-diversity trajectory, in which some countries are at different points than others.

At the same time, Latin American boards cannot hope for time alone to rectify the situation. The changes that have taken place in Europe and the United States and Canada have occurred because the companies and countries in those regions took multiple proactive steps toward boardroom gender diversity. If Latin America is to close the boardroom gender gap as other regions have done, it must decide to do so. While there is no single answer to increasing boardroom gender diversity, we offer the following six points for consideration:

- Boards, and particularly chairmen, need to view boardroom gender diversity as part of the cost of entry into the upper tier of global corporate citizenship. It is unavoidable that they will be scrutinized by shareholders and others on this issue.

- Nominating committees need to assume that while there may not be as many qualified female director candidates as male candidates, suitable female candidates do exist. Identifying them will require the proactive decision to look beyond previously tapped networks. Companies elsewhere that wish to increase the number of women on their boards have found it helpful to institute an internal rule stating that at least one woman should be in the pool of candidates considered for an open board position.

- Boards should use the discussion on gender diversity in the boardroom to reexamine the criteria for selecting directors. Boards looking to fill director seats would benefit from thinking about the competencies and experiences that need to be added to the boardroom table, instead of limiting candidates to those that already belong to their network, who are current or former CEOs or who hold a particular qualification. A competency-based approach to filling board seats will not only increase the pool of available women, but it will allow boards to identify a wider pool of potential members to help it contend with the challenges and opportunities of digital transformation and changing customer expectations.

- Board members should also work together with senior executives to increase the number of women in P&L leadership positions. Doing so will require proactive steps to address work-life balance policies for both men and women within the company. Addressing these issues will allow the organization to more fully tap into its human capital while collectively strengthening the region’s pipeline of female board members.

- Women who wish to be on track for board membership need to proactively position themselves. Being considered a potential board member requires a successful track record of P&L leadership and the visibility that comes from strategic networking and public speaking. These remain the requirements despite the fact that many society-wide issues regarding cultural bias and work-life balance still need to be resolved.

- National corporate governance organizations and influencers should facilitate dialogue and transparency regarding boardroom gender diversity by collecting and disseminating data on diversity at companies and on qualified women, sharing best practices and facilitating networking among potential board members.

We previously noted that the differences between the boardroom gender diversity statistics of Latin America and those of Europe, the United States and Canada failed to take into account the element of time. But the numbers also fail to capture the existence of a robust range of views among Latin American board chairs on the issue. Yes, there are board chairs who have not yet made boardroom gender diversity a priority. But there are others who see the importance of this goal and are working toward it in their own way. And still others are fully engaged with the complexities of underlying factors such as work-life balance. A range of opinions is very different from silence and indifference. And the women who are now board members form an important chorus of voices that cannot be ignored. From this dialogue we are confident that progress will unfold. As it does, we at Egon Zehnder look forward to contributing to the process.

Access the full study 2016 Egon Zehnder Latin American Board Diversity Analysis.

1 These countries were chosen because there was enough available data on the companies there to yield meaningful results.

2 Data for this survey was taken from BoardEx as of July 2015, with corrections and clarifications made by Egon Zehnder Research. Of the 155 companies from Latin America, 10 were from Argentina, 70 from Brazil, 22 from Chile, 12 from Colombia and 41 from Mexico.

3 World Family Map 2014, Social Trends Institute

4 In addition to the 155 companies from Latin America, this section includes data from 1283 companies from Europe and 2091 companies from the United States and Canada, all with a market capitalization of US$1 billion or more.

5 This assumes that the annual board member turnover rate and the rate of new appointments to the board held by women remain constant in each region over time.

2016 Egon Zehnder Latin American Board Diversity Analysis

Download as PDF

In the news:

The Wall Street Journal – Study Reveals Lack of Women on Latin American BoardsView related study:

2014 Egon Zehnder European and Global Board Diversity Analysis