Introduction

Introduction

Protecting the brain’s processing power has been important to our evolutionary history. The brain relies on “shortcuts” (intuitions, gut feelings, common sense, muscle memory, instincts, etc.) to conserve processing power. This happens through instantaneously linking situations to patterns from memory and applying stored solutions to upcoming decisions. People can misunderstand the nature of intuition and portray it as irrational. It isn’t. It is a rational but unconscious process of making decisions that suffices for most daily decisions. Only a small minority of decisions deploy the conscious processing power of the brain.

Both our intuitions and analyses are more often than not correct and are essential to our survival and thriving as a species. However, both are also prone to errors. The study of these errors is the field of cognitive biases.

There are close to 200 known cognitive biases. The most common and relevant biases that we have observed in senior talent decision settings are listed below alphabetically. You may want to add to or shorten the list based on your own experiences. They don’t all apply to every situation, and in some cases, they may even counterbalance one another. These are effectively the higher-order processing flaws that could impact a range of underlying decisions that can negatively affect DEI outcomes.

- Ambiguity bias: The tendency to avoid options for which the probability of a favorable outcome is unknown (e.g., viewing diverse candidates as higher risk).

- Authority bias: The tendency to attribute greater accuracy to the opinion of an authority figure unrelated to its content (e.g., the boss/expert knows best).

- Anchoring bias: The tendency to disproportionately rely on one piece or a narrow set of information, usually received first or early, to guide decisions (e.g., receiving strong positive or negative commentary on someone).

- Affinity bias: The tendency to be naturally drawn toward individuals with similar characteristics, backgrounds and interests (e.g., alumni of the same university).

- Attractiveness bias: The tendency to associate more favorable characteristics with those who may look or dress in conventionally desirable ways.

- Attribution bias: The tendency to overemphasize personal factors and underestimate situational factors when evaluating an individual (e.g., ignoring macro situations and benchmarks while evaluating performance, positively or negatively).

- Confirmation bias: The tendency to selectively search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions (e.g., in final referencing for candidates).

- Conformity bias: The tendency to adapt our own opinions to fit with those of a group.

- Effort justification bias: The tendency to attribute greater value to someone’s success if you have had a role in supporting them (e.g., when favoring internal candidates or those you have mentored or worked with in the past).

- Egocentric bias: The tendency to place a higher emphasis on and belief in the accuracy of one’s own perspectives than those of others.

- Halo bias: The tendency for positive aspects in a profile to spill over and positively influence the view of other unrelated aspects (e.g., “They went to Harvard, they must be good.”).

- Horn bias: The tendency for negative aspects in a profile to spill over and negatively influence the view on other unrelated aspects (e.g., not hiring someone who worked for a company that had bad press).

- Objectivity bias: The tendency to believe that one is more objective and unbiased than others.

- Present bias: The tendency to favor lower immediate payoffs relative to greater later payoffs (e.g., “We cannot wait for a better candidate; we need to solve this now.”).

- Status-quo bias: The tendency to favor the default or incumbent situation in comparison to making a change (e.g., “They are not performing; let’s give it six more months.”).

- Zero-risk bias: The tendency to prefer reducing a small risk to zero over a greater reduction in a larger risk (e.g., refusing to accept any compromise in prior experience at the expense of the much greater overall benefits another candidate could bring).

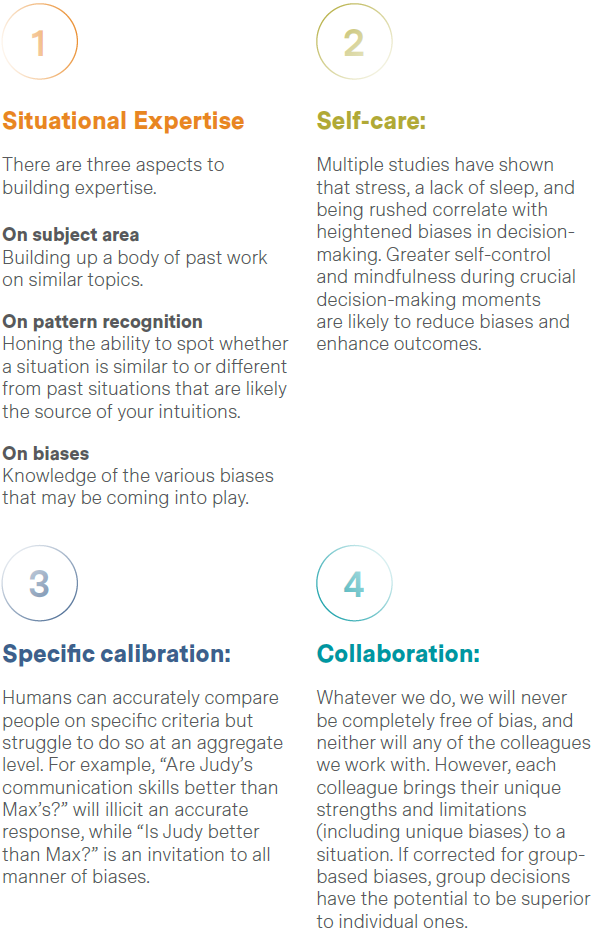

Pathway to reducing Biases

Pathway to reducing Biases