Strengthening the diversity of top academic leaders

Findings and insights from Egon Zehnder’s Global Academic Leadership Survey

Most leading academic institutions are strongly committed to diversity, a commitment visible in their policies on staff recruitment and student admissions, as well as in their academic programs. Yet how diverse are their leaders? A survey by Egon Zehnder of over 300 top universities and research institutions worldwide shows that the most senior level of academic leadership remains overwhelmingly male and locally-born.

This finding should worry institutions’ governing boards for three reasons. First, the degree of diversity at the top sends a powerful signal about what the institution stands for. Further, there are strong indications that diversity of perspective is a crucial driver of innovation and creativity in organizations. Last but not least, there is evidence that today’s low levels of leadership diversity reflect search and selection procedures that often overlook nontraditional candidates for institutions’ top posts.

This article profiles the research findings, discusses their implications, and shares examples of how a more professional search approach can offer universities and research institutions a significantly more diverse slate of outstanding leadership candidates. Of course, diversity in academic leadership is a complex topic, and the article does not attempt to address all its facets. Rather, our intention is to initiate a conversation amongst governing boards and selection committees on how to strengthen diversity at the top – and to suggest several concrete steps that can help them do so.

A lack of diversity at the highest levels of academic leadership

To create a global fact base, Egon Zehnder analyzed the curricula vitae of the top leaders of several hundred leading academic institutions across Europe, the USA, and Asia. The top universities and the research institutions were identified according to ranking, size, and reputation, in each of ten countries or regions: Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the USA, the UK, the Benelux countries, Scandinavia, Japan, Singapore, and South East Asia (including Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand).

The CV of each institution’s top leader – its Rector, President, Vice-Chancellor, Managing Director, or CEO – was then analyzed along several dimensions of diversity, including gender, age, nationality, country of birth, and years spent abroad. In total, the study sample consisted of 336 individuals, with the sample size for each country or region varying between nine and 81 academic leaders. Finally, expert interviews and in-depth analyses were conducted to understand the underlying reasons for the findings, draw out their implications, and highlight areas for action by academic institutions and other stakeholders.

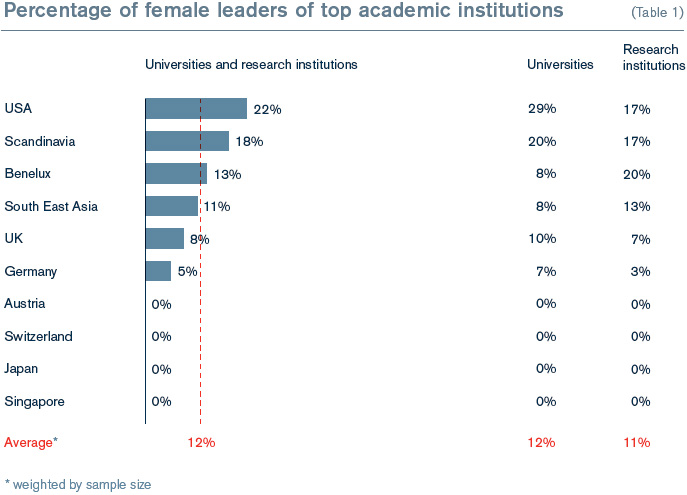

The findings, compiled during 2011, paint a stark picture. For starters, women are dramatically underrepresented amongst the top leaders of academic institutions: Across the countries studied, only 12% of academic leaders on average were female (Table 1). Only in the USA and in Scandinavia does the percentage of women in top leadership positions reach around 20%, reflecting concerted efforts in those regions to strengthen gender diversity. In several of the countries analyzed there were no female top leaders at all amongst the preeminent academic institutions.

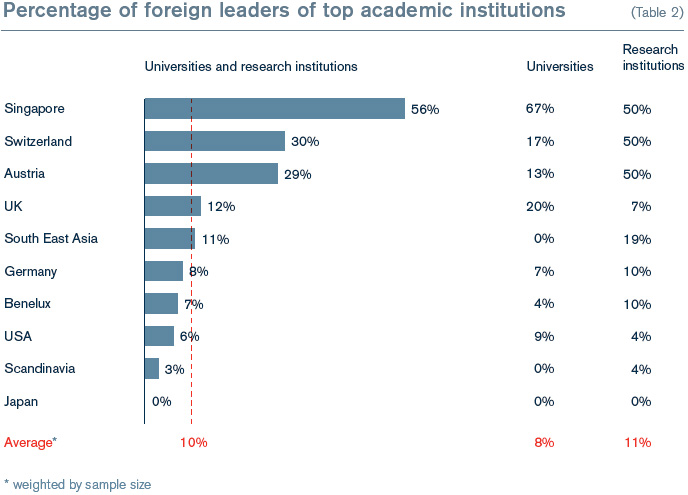

Further, the overwhelming majority of academic leaders in most countries were citizens of those countries, with only 10% of the leaders being foreign citizens and 13% foreign-born (Table 2). Again, there were significant differences, both between regions and between universities and research institutions. In Singapore, more than half the academic leaders identified were foreign, reflecting a conscious drive by that country to recruit leading foreign academics in line with a vision to create top-ranked international universities – and a willingness to pay a premium for such leaders. In the neighboring countries of South East Asia, however, none of the university leaders were foreign, reflecting internally focused recruitment and promotion processes. Only in those countries’ research institutions, which have greater private sector involvement, was there any foreign leadership.

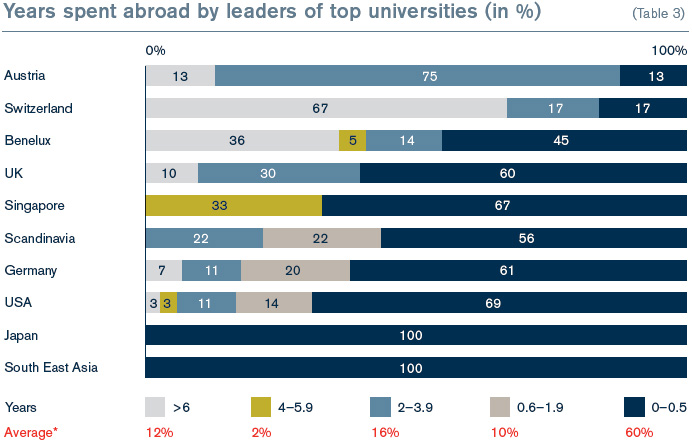

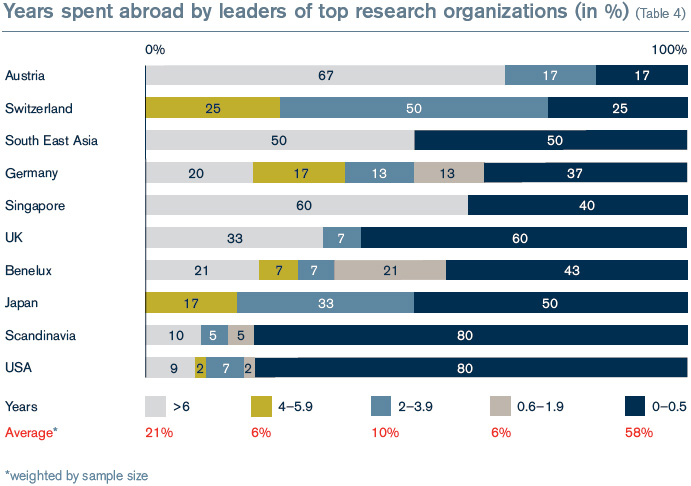

Moreover, the majority of the leaders in the sample had spent little or none of their careers outside of their home countries (Tables 3, 4). Some 60% had spent less than six months of their careers abroad, although 30% of university leaders and 37% of leaders of research institutions had spent two years or more abroad. Again, there were significant variations across regions. In the smaller European countries, including Austria, Switzerland, and the Benelux nations, most leaders had spent substantial time abroad. The extensive foreign experience of Austria’s academics might reflect a long-established culture in that country of scientists and top academic leaders spending a significant part of their careers abroad. But in the USA, a vast country with an extensive network of excellent institutions, fewer than 20% of leaders had spent two or more years abroad.

Finally, the study calculated the average age of academic leaders in each of the countries or regions in the sample. In almost every one of them, leaders were on average in their late 50s or 60s, with a global average age of 59. Singapore was again the outlier, with an average age of 54 amongst its top academic leaders, reflecting the country’s willingness to hire top international academics into senior roles at earlier stages of their careers.

Why achieving greater diversity should be a priority

These findings show that the world’s leading academic institutions have a long way to go if they are to achieve true diversity at the top. Granted, they are not alone in facing this challenge. According to our own surveys, only 12-15% of corporate board members worldwide are female. Another study found that the proportion of top business leaders who were foreign amounted to no more than 5% of the total across Germany, France, the UK, the USA, China, and Japan. The same study found that only a quarter of top business leaders in those countries had significant international career experience.

Addressing these current low levels of diversity at senior leadership levels is not only a matter of fairness and equity. There is also much indication that diversity strengthens organizational performance, particularly in environments – like academia – in which innovation and creativity are critical drivers of success.

Egon Zehnder’s own strong view, based on our work with major organizations across the world, is that different backgrounds, experiences and educational profiles endow senior teams with what we call “diversity of viewpoint.” Such diversity, beyond simply promoting representation of particular demographic groups, enriches discussion and decision-making amongst leadership teams and enables them to tackle familiar problems in new ways. It is therefore a crucial enabler of innovation and excellence.

Low levels of diversity at the top could therefore be a real inhibitor of academic institutions’ development and performance. At the same time, there is increasing societal pressure to strengthen diversity. In just the last few months, for example, the UK has seen the publication of the governmentcommissioned Davies report, recommending a range of measures to improve the gender balance on company boards; and Malaysia’s Prime Minister has announced a target of 30% female board representation for large companies. The expectations placed on academic institutions to strengthen diversity are perhaps even higher than those on business, given that their leaders are role models not just for diverse student bodies but for society as a whole.

It is therefore an opportune time for academic institutions to consider what barriers stand in the way of greater diversity at their senior leadership levels, and what they can do to address them. In our extensive experience of international talent markets, the availability of diverse talent is certainly not the major barrier to greater diversity, even if the pool of potential female candidates may be somewhat smaller in fields such as engineering. The experience of female academic leaders in the USA, and of foreign academic leaders in countries such as Singapore and Switzerland, underlines the fact that there are already numerous successful leaders of premier academic institutions who do not fit the traditional “male, local, and 60ish” profile.

Rather, the greatest barriers to diversity in academic leadership lie in the structures, cultures, and operating environments of institutions. In many countries, for example, academic institutions’ salary scales are inflexibly linked to those of the local civil service, making it very difficult to attract top international talent. In most countries in South East Asia, for instance, academics are de facto civil servants, which makes it difficult for universities to offer foreign academics more than 50% of what they would earn in the USA. Singapore, by contrast, is willing to pay top international talent a 15-20% premium over US salaries as part of its strategy to build world-class institutions. Beyond the issue of pay, many countries treat managerial posts in academia as jobs-forlife, and apply limited performance management: The effect is that openings for a new generation of diverse, innovative leaders can be few and far between.

Some of these barriers are deep-seated issues that must be addressed as part of broader educational and political reforms. For one thing, governments might need to allow academic institutions greater flexibility in remunerating their top positions, to enable recruitment of the best global leaders. In this regard, greater use can be made of arrangements such as job rotations and limited-term contracts, which make it much easier for institutions to appoint foreign high-potential talent to their staff.

More broadly, some countries may need to adopt explicit and ambitious visions to build world-class, internationally relevant institutions with a high proportion of foreign leadership – as Singapore has done. Further, many institutions can significantly strengthen their performance appraisal and management systems, for example by introducing probation periods and 360 degree feedback for academics and leaders, to ensure that high performers are developed and rewarded and that low performers do not inhibit the entry of new talents.

Some barriers, however, can be addressed much more rapidly and lie closely within the control of individual universities and research institutions. In particular, there is an opportunity in many institutions to professionalize the search and selection process for senior leadership positions.

Strengthening search and selection

ur experience in working with leading academic institutions suggests that many could significantly improve the diversity of their leadership by adopting more thoughtful and systematic search and selection procedures. The best such procedures have two defining characteristics. First, they are professional – they take a structured, systematic approach to identifying and evaluating the strongest possible slate of candidates. Second, they are global, searching for leading talent with equal thoroughness in all major markets.

Today, however, we observe that many institutions fall short of this bar. Longlists tend to be populated with candidates who are known to (and demographically similar to) the selection committee, on the assumption that the pool of potential leaders is small, specialized, and personally acquainted with the senior academics undertaking the selection. At the same time, many institutions fail to undertake systematic global searches for leadership candidates, focusing instead on the local market – thus limiting their scope from the start. The result is often that candidates from nontraditional backgrounds simply do not make it onto the longlist.

This is exactly what happened in a recent search for a new Rector of a leading European university: The selection committee identified what it believed to be an exhaustive list of 36 candidates through an informal search process drawing primarily on its own networks. However, a professional recruitment process subsequently widened the pool of candidates to include several outstanding individuals the committee had not identified – and some whom it had identified, but had assumed would not be interested in the post. One of these candidates was ultimately appointed to the top job. We have seen the same happen in other academic institutions, where professional search processes have identified outstanding yet nontraditional candidates, for example government and business leaders with strong academic backgrounds. Although the appointment of such candidates can be a calculated risk, several such individuals have gone on to become top-flight academic leaders.

We believe strongly that a professional recruitment process is needed to break through the in-built bias of the “we all know each other” mindset, and to identify promising candidates who might otherwise be hidden. This recruitment process should be explicitly global, drawing on the best sources of talent in all major markets. And it may also be necessary to draw up a substantial slate of “diversity candidates,” including women and minorities, to heighten selection committees’ focus on both the challenge of improving diversity and the availability of diverse leadership talent. Such slates would require search firms, ourselves included, to invest in carefully screening the market for women academic leaders – adding further impetus to the push for diversity.

Finally, there are opportunities in many institutions to redesign the interview and evaluation process for senior leadership positions. Loosely structured interviews by a large group of selection committee members can result in subtle biases against candidates who are demographically dissimilar to the majority of interviewers. Further, the decisions-by-committee that result can often converge around “safe” candidates and exclude those seen as risky. By contrast, a series of structured interviews conducted one-on-one or in small groups, using robust evaluation metrics and peer references, can deliver a shortlist based on much more objective criteria – and so remove the often unconscious cultural biases than can prejudice nontraditional candidates.

Many universities and research institutions are strongly committed to diversity, yet have struggled to translate this commitment into reality at their most senior levels of leadership. What is needed is a concerted push to strengthen recruitment – making the search bolder and more systematic, and the selection process more rigorous. These steps in themselves could unlock significantly greater diversity at senior levels of academia. They will have even greater impact if they are coupled with more readily tailored employment conditions, stronger performance management, and policy reforms that explicitly promote academic excellence.