“The students must see themselves as building a cathedral – the cathedral being Africa.”

Widely acknowledged as one of Africa’s top young leaders, Fred Swaniker explains how his African Leadership Academy aims to help a whole continent fulfill its immense potential.

Plagued by decades of poverty, corruption, and warfare, Africa is finally beginning to emerge from a troubled postcolonial era of poor leadership. While much still needs to be done in these new and fragile times – nation building, peacekeeping, and planning for a dynamic but complicated future – a young educational entrepreneur named Fred Swaniker is already hard at work developing the one asset he feels will help ensure a brighter future: properly trained leaders. In recent years his organization, the African Leadership Academy (ALA), has begun training talented youngsters from across Africa. His aim? To develop a generation of future leaders who will transform the continent. It’s a breathtakingly ambitious and inspiring initiative.

The Focus: After so many years of corruption and poverty, Africa is now widely perceived as a continent on the rise. How has that come about?

Fred Swaniker: Africa is where China was 20 or 30 years ago. It is starting to awaken from its slumber and many different trends are coming into place that are making it the next great economic frontier. The most fundamental change has happened at the leadership level. We have seen three generations of leaders, and each generation has left a different legacy for Africa.

Can you describe those generations and their legacies?

Generation one was the leaders who brought independence to Africa – Kwame Nkrumah from Ghana, Julius Nyerere from Tanzania, and so forth. They were fighting to get rid of colonialism. By and large they achieved that mission and must be recognized for that legacy, but many of them went on to become dictators.

Generation two – the leaders who came after them – had the worst legacy and a horrible impact on Africa. These were the corrupt dictators, people who abused human rights. Rulers like Idi Amin of Uganda, Sani Abacha of Nigeria, Mobutu Sese Seko from the Congo – they plundered and pillaged Africa. Thankfully, most of that generation is gone.

Generation three is the leaders who have emerged in the last 15 years. The main legacy of this generation is that they’ve stopped the fighting. This is Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in Liberia, it’s Kagame in Rwanda, and Nelson Mandela – they have brought more peace and stability to Africa. Just 25 years ago, 33 of 54 African countries were engaged in some form of conflict. Today this figure is about five. The cessation of the conflicts and improvement in political stability are the most fundamental changes that are allowing Africa to grow.

To what extent is this positive development also being driven by demographic trends in Africa?

Consider urbanization: over the next 40 years, 800 million people are going to move into African cities and that is going to be a huge force for economic growth. Cities are the building blocks of the market economy. They bring people who have goods and ideas to sell together with those who want to buy, and you can build infrastructure and real estate in a much more concentrated way. This is driving growth in Africa. Another big shift is population growth – Africa has the fastest population growth in the world. By 2030, Africa will have a larger work force than China. And the population is very young. The average age in Africa is 18, compared to 44 in Germany. At the same time, birth rates are falling, so people have fewer dependents to support and therefore more disposable income. These are trends that represent a great deal of potential for the continent.

On the other hand, if not managed properly, couldn’t all of these potential opportunities quickly become downsides with a lot of risks?

Exactly. And this is where leadership really comes into play, because leaders are going to make the difference. They are going to decide whether all these trends we are seeing in Africa remain positive and powerful engines for growth, or a recipe for disaster. But the leaders that are emerging – generation four – are the people we are grooming here and they will make the difference.

It sounds as if generation four will have a great deal of hopes and responsibilities resting on its shoulders.

Only history will tell if I am right, but I have a vision that its legacy will be bringing prosperity to Africa. Unless we can create wealth on this continent, and create enough jobs for all of these people, we will never become truly independent. We won’t be able to feed our own children, build our own roads and schools, or fund our own healthcare. All of these things we need to do. This new generation that is coming up must make sure that this is their legacy. I tell them that what we are doing here is akin to the work of the cathedral builders of Milan. It took 400 years to build the cathedral. Many people started working on it and died before their work was finished. And today you go to Milan, and you see this beautiful building and it has so many benefits for society. What we teach our students is that with their jobs as leaders, they won’t necessarily live to see the full impact of their work. But they must see themselves as building a cathedral – the cathedral being Africa.

Is there any such thing as a global notion of leadership or does it change from one country or continent to the next?

The way I look at a leader is as an agent of positive change, because in every situation in every country, in every context, there are people who act as catalysts, who change the status quo. And those are the leaders that really bring progress to everything – to society, to human beings. Consider the change that happened here in South Africa: if it wasn’t for Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela, we wouldn’t have seen that change happen.

Is it – compared to other continents – perhaps easier for a leader to drive change in Africa?

Let me put it this way: the impact of a given individual in society is much greater here in Africa than anywhere else in the world. That is because the impact of a leader, or indeed the need for a leader, is negated by the strength of the institutions that exist. In the United States, for example, there is a 200-plus year-old constitution, Congress, a judiciary, and even the Federal Reserve. In Africa, we don’t have those sorts of institutions with the strength to keep leaders and their power in check.

“We are not going to become prosperous without entrepreneurship.”

You have often said that Africa needs more entrepreneurs. So far we’ve been talking about political and spiritual leaders. How are these different forms of leadership related?

We are not going to become prosperous without entrepreneurship. The government can’t generate prosperity. Foreign aid won’t generate prosperity. We need African entrepreneurs who are going to build enterprises on a scale that will create the hundreds or thousands of jobs that we will soon need. We have a concept that we teach at the Academy called “entrepreneurial leadership”. It’s a mindset about seeing all of the challenges that exist in Africa also as opportunities. The best definition I ever heard of entrepreneurship is “the art of doing much more than anyone thinks possible with much less than anyone thinks possible.” If you think about the lack of resources we have in Africa, whether you go into politics, healthcare, or whatever, you are going to need this kind of entrepreneurship.

How did you arrive at the concept behind the African Leadership Academy? What led you to believe that an institution like this was needed – and possible?

After living and working in many countries across this continent, I came to realize how much potential Africa has. But what was consistently holding us back was the lack of good leadership. I realized that unless we increase the supply of good leaders in Africa we are never going to fully realize all the potential that we have on this continent. So I asked myself: can we create a production line for leaders with the potential to transform this continent? That was the vision behind the Academy.

We began the project ten years ago and today we already have nearly 600 young leaders under development. Our goal is to develop, over a 50-year period, 6,000 leaders who are going to transform Africa. The kinds of leaders we are creating are not leaders who will solve our small problems, but our biggest problems; people who are going to lead at the national level and be presidents of countries, central bank governors, or CEOs of major corporations; people who are going to come up with innovations that will impact the lives of millions of people whether it is in healthcare or infrastructure or education; people who are going to really make a significant difference to this continent.

It must be quite a challenge to choose your students from among thousands of applicants from all over Africa and from such diverse backgrounds. How do you identify their potential?

This year we received 4,000 applications from 46 countries, and we can only take 100 of them, or 2.5 percent. We are looking for people that we believe can transform Africa; people who share certain attributes that we think make great leaders. The one thing that we think distinguishes great leaders is perseverance. We are looking for people who don’t give up when they are faced with an obstacle, because the job of leading is a difficult one. We are looking for people with courage – because if you really want to drive change, you must have courage. We also believe that great leaders have passion – which is about being obsessed with something and not sleeping until you achieve it. It’s that passion that is going to allow them to keep going when times get tough. Finally, we believe that great leaders can tell right from wrong. We are looking for people who have good values and are going to make the right decisions when faced with ethical dilemmas.

In the context of our consulting, the decision process that leads to the selection of one candidate and the rejection of another is central to our work. So we’d be interested to learn exactly how you create a shortlist when there are so many interesting candidates.

We shortlist that initial crop of candidates by asking them to tell us about a time they identified a need in their community and, crucially, what they actually did about it. The idea is to distinguish the talkers from the doers – the ones who actually had the courage and the perseverance to step up and do something about it. That is when we hear the fascinating stories. “There was no electricity in my village, so I built a windmill and created electricity for the village.” Or “The math teacher in my class used to come to class drunk all the time, so I took over and I became the math teacher.”

These are real stories?

Amazingly, yes. And so is this one: “There was no school in my refugee camp so I built the school.” One young woman from Kenya, who is studying here with us now, grew up in an impoverished part of the country and needed to help her family earn a living. She started a little business rearing rabbits. By the time she was 14, she was employing 15 women and had created a micro-finance fund, which spun off three other businesses for three other women. This is the sort of thing our students have done on their own without any investment in them, without any networks.

Imagine what they can do if you really invest in them; if you connect them with others like themselves; if you surround them with such entrepreneurial energy and passion for change – imagine what can happen for Africa!

Look at all the innovation coming out of Silicon Valley. When I went to business school there, I always used to wonder what’s so special about Silicon Valley. Is it the water that they drink there or the air that they breathe that creates all this innovation? The only difference that I found was that they’ll take a 17-year-old kid with an idea seriously, and they’ll give him an opportunity.

Apart from creating strong personalities, you are surely also keen to build stronger institutions in African countries. How do you combine the two goals?

One of the messages that I try to instill in our young leaders here is that they must use the window of opportunity that they have in the absence of strong institutions to bring tremendous change in Africa. But one of the legacies that they must leave as leaders is that they must build those institutions, so that when they are gone, their good work can continue. The reason why Mugabe was able to destroy Zimbabwe in ten years is because there were no institutions to prevent him.

Once you’ve identified those future leaders, what approach does the Academy adopt? Do you focus on strengthening the existing roots or try to add different and additional skills? What about the balance between knowledge and personality, character and leadership potential?

When our students join us they have already demonstrated potential, but we believe you only become a great leader through practice! What they bring with them is just the foundation. When they come here we build on that foundation by giving them hands-on practice, as well as ongoing mentorship and inspiration. They soon set their sights higher and really develop their skills as leaders. We don’t see the ALA as an educational institution in the normal sense, but rather as a leadership factory. Our first goal is leadership development, not education. Having said that, of course we also give our students a basic education. If you are going to become the finance minister of a country one day, you need to understand economics. If your passion is healthcare and you want to eradicate HIV/Aids in Africa, you need to understand biology. So they obviously get that intellectual foundation, and they learn how to write effectively and speak in public, all the kinds of things that they’ll need as leaders one day. And we see ourselves staying engaged with them as they progress in life, as they go on to university.

In most cases that means they leave the country…

Yes, about 80 percent are admitted to leading universities around the world.

And ideally, when they graduate, they come back to Africa. How do you make sure all that potential doesn’t end up working abroad?

If you are trying to develop a leader who is going to transform a continent, it is not going to happen in the initial two years, so we have a whole team that works with our alumni. During their studies we bring them together for professional development seminars around the world where we help them think really hard about their career options. Then every summer we bring many of them back to Africa for internships. But the greatest force for bringing our students back to Africa is passion, a passion for the continent. Also, when they graduate from college, we are not going to leave it to the Harvard or Stanford career office to put them in a job in Africa, because they don’t have the resources we do. We are building relationships with governments, corporations and organizations that are looking for this talent. And I would argue that we have a warehouse of the best talent in Africa. A lot of companies are growing in Africa, and one of the biggest challenges they face is accessing talent. We want to connect with all of these entities that are looking for talented young people, so we have a full-time team that is just doing that.

If we had launched the ALA 20 years ago, it would have been a very different proposition, because Africa was a continent of warfare. But today, Africa is a continent of opportunity. Our students come back because this is where the opportunities are.

The graduates supply the skills and competencies, you supply the contacts…

Yes, because the other thing I believe really deeply is that your effectiveness as a leader is partly a function of the skills that you have, but it is also hugely dependent on the networks that you have. No matter how good you are as a leader, if you don’t know the right people who can be potential partners in what you are doing – potential employees, people who can mentor or invest in you – you might not succeed. It all comes down to collaboration, which is why we work so hard to keep intact the network that we are building.

“If you put someone in a leadership role that is not really congruent with their passions, they are out of equilibrium.”

How do you make sure that you don’t focus entirely on the business sphere at the expense of the public sphere? Are you educating or grooming enough public leaders?

We don’t try and dictate what our young leaders should do. I think that if you put someone in a leadership role that is not really congruent with their passions, they are out of equilibrium. As a leader you can only be out of equilibrium for a certain period of time before you either become ineffective or spin out of control. We believe that you need to merge your passion with your leadership skills, and we find that by nature about one-third of the young people who come to ALA are interested in politics and in the public sector, and we absolutely encourage them in this. Another third want to be hardcore entrepreneurs – the African equivalent of Bill Gates.

If that is their passion, then we encourage that, too. The other third are interested in science and technology, and they want to be the geeks who are going to come up with the amazing innovation that will transform Africa.

We spoke earlier about leaders and their legacies. In many ways, the ideal legacy is the result of reaching one’s full potential. What do you personally hope to leave behind for your successors? And how do you aim to ensure that this institution survives you?

I admit I am slightly obsessed with succession planning and making sure that anything I build survives me, because the journey that we started here is a 50 to 100-year project. This institution must last that long to reach its full potential. And it must be strong enough to benefit from regular changes in leadership over time. From the beginning I have tried to empower a group of other leaders around me. When I began this, I told everyone here that in five years I was going to move on. Five years later, it wasn’t quite ready, so I set myself another five years – but that “I’m going to move on” mindset forces you to constantly say: “Who around me can take this mantle on and how do I share decision-making responsibility? How do I empower people and create systems and processes so that things are not dependent on one or two people?”

My dream is that in ten years’ time this institution will be run by one of our young leaders and I tell them that all the time. We are very fortunate in that, unlike most institutions in the world, we are literally growing our own talent from scratch. I hope one of those people will be my successor. I will always be involved for the rest of my life, on the board, helping to raise funds and so forth. But this institution isn’t about me. It’s about the future of Africa. It’s about a continent reaching its potential.

The interview with Fred Swaniker in Johannesburg was conducted by Xavier Leroy, Egon Zehnder, Johannesburg, and Ulrike Krause, THEFOCUS.

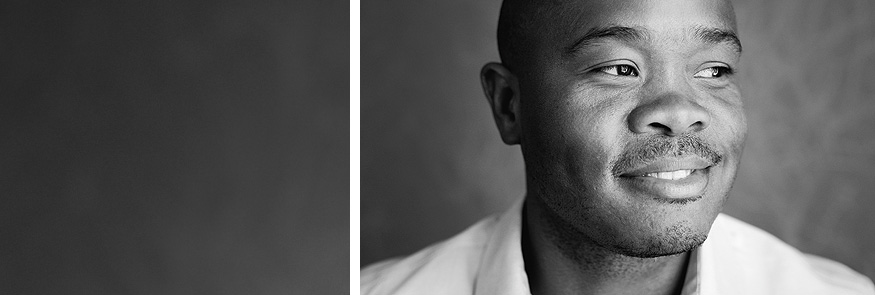

Fred Swaniker

Fred Swaniker was born in Ghana into an upper-middle-class family with a background in teaching and founding schools. His family lived in several African countries, including Gambia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. As an adult, he also lived and worked in South Africa, Nigeria, and Tanzania. Swaniker graduated in Economics at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, and worked for McKinsey and Company in the USAand Africa before attending Stanford Business School. He has won global recognition for his achievements: Echoing Green named him among the fifteen “best emerging social entrepreneurs in the world” (2006); he was selected as one of 115 young leaders to meet with President Obama (2010); Forbes magazine listed him among the top ten young “power men” in Africa (2011); and he is a Fellow of the Aspen Institute’s Global Leadership Network.

The African Leadership Academy (ALA)

The ALA, located outside Johannesburg, South Africa, opened its doors in 2008 and offers a two-year pan-African pre-university program. The Academy is open to young people from all 54 African nations, regardless of religion, gender, or race. Following a rigorous application and screening process, the students are schooled in African studies, leadership, and entrepreneurship. The ALA aims to groom Africa’s next generation of leaders with a stated goal of 6,000 leaders or ‘change agents’ graduating over the next fifty years.

PHOTOS: FRITZ BECK