“The ideal Juilliard student has great intellectual curiosity and a desire to be a leader.”

A conversation with Joseph W. Polisi, President of the prestigious Juilliard School, about the identification of outstanding artistic talent – and how to help it unfold.

As one of the world’s premier performing arts academies, Juilliard has spent well over a century identifying and nurturing top talent in music, and later dance and theater as well. Joseph W. Polisi became the Juilliard’s sixth and current president, beginning with the 1984-85 academic year, and has been seen as a transformative figure in arts education, concentrating on significant additions to the curriculum, particularly in the area of community outreach. We met with Joseph Polisi at Juilliard’s impressive headquarters in the heart of New York City’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. While touring the school on a sunny autumn afternoon, observing studies in drama and dance, we were delighted to encounter the Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, Maestro Alan Gilbert, teaching a young conductor and rehearsing with the talented students of Juilliard’s own orchestra.

The Focus: For many, Juilliard is synonymous with the sort of competitive excellence and rigorous dedication that comes with training top artistic talent. How does Juilliard identify that talent in the infancy of its potential, so to speak?

Joseph W. Polisi: To begin with, we still have a very traditional audition process that is as old as the history of music. But more generally, for faculty members or musicians who know their discipline, it actually is quite easy to identify extraordinary talent very quickly.

What are the indicators that you’re looking for to help assess potential and predict future success?

First of all there is a significant difference in how one evaluates musicians as opposed to actors or dancers, and within music itself there is also a difference. For example, a 17-year-old violinist, pianist or cellist will be quite advanced, and at Juilliard we will expect to find a significant technique and artistry by the time they audition at this age in those instruments. With voice, because that is a later maturing instrument we adjust our expectations accordingly.

And with your dance and drama applicants?

In dance, there is a good deal of craft and technique expected and it is somewhat akin to how I would say one looks at music. However, in drama we look mostly at potential, imagination and creativity. This is our most selective area, where we have 1,500 applicants for 18 places, so we accept less than one percent. In some areas, the applicants will have a good deal of experience and we’ll immediately see some sort of talent, a certain level of technique. In other disciplines, we mostly see imagination, creativity, improvisation skills, and a sense of risk-taking – all of the things that are necessary in those fields.

Those skills are surely important in assessing musical talent as well …

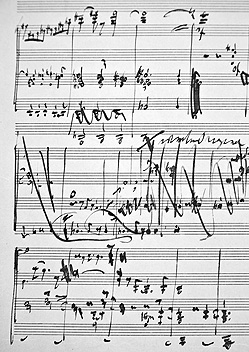

Sure. You can hear one person play Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme for cello, and they may have all the notes right. But another person will have not only all the notes right, but all the imagination and creativity and shaping that this piece demands as well.

How do you seek out this talent, given that it must be global in nature and in some cases hard to find?

Our faculty does in fact invest a significant amount of time traveling the world, listening to young talent in workshops, master classes, and competitions. If we find talent, we suggest that they come to Juilliard and audition if they want to enroll. And, of course, we seek out local talent here too, in the public schools, disadvantaged neighborhoods, and rural areas.

What isn’t revealed in an audition? Are there things that you look for in terms of a person’s character?

Their intellectual curiosity. We hold interviews; we look at transcripts, recommendations, essays, and so on. But we also look into who that person is.

How do you do that?

The research becomes more extensive and deeper as the programs get more advanced. For example, for our doctoral program, which is also highly selective, we have an extensive series of examinations and interviews. For an undergraduate we will talk to them at some length to get a sense of what they are interested in. The ideal Juilliard student is someone who is not only a very interesting artist, but also has great intellectual curiosity, has a sense of their own world, and a desire to be a leader – to make a difference through their art. But in order to get through the door, you still have to pass the audition.

What about the temperamental artists – the ones whose technique and expressiveness are just perfect but who other-wise don’t have the attributes you’re looking for?

We try to work with the young person, to develop their own sense of themselves, their own social intelligence. But to be honest, Juilliard doesn’t have enormous patience in this respect. There are no students at Juilliard who are trained to be just soloists, although they may eventually become soloists. For example, every student plays in an orchestra; there are no exceptions. And it’s the same with chamber music. I am personally not very patient at all with so-called artistic temperament. The vast majority of the successful artists I have met are not difficult to deal with at all – as long as you understand what their needs and priorities are.

How successful is Juilliard at picking young talent, at undergraduate level, for example?

The graduation rate is very high; there is very little attrition. I think one of the most rigorous aspects of the Juilliard experience is the admissions process. We are absolutely vigilant about that, and there are no compromises. Once students gain admission, we really do work with them on their growth as artists and as young adults.

So if they get in, you know they will run the course?

We don’t know one hundred percent of the time, and there are cases of individuals who can’t handle the pressure. Having said that, of all the pressure they are under while they are at Juilliard, by far the most comes from within. We know this for a fact. They are the ones who are pushing themselves.

Is there a single most important reason for cases where your prediction of future potential doesn’t come to fruition?

There could be a whole host of problems. The simplest is that they did a spectacular audition and will never do that again in their lives. That does happen once in a while. Then there are psychological issues, or physical issues in terms of stamina, and even cultural issues about time management. Remember, 33 percent of our students are international students, so they are coming here with enormous cultural and language differences, and just plain homesickness can be an issue. I don’t think any school of any stature can predict success 100 percent of the time. It’s just not possible.

Leaving aside the technical expertise for a moment, how does Juilliard help young talent fulfill their potential in terms of their mental and personal development?

We work with all faculty – studio faculty, classroom faculty – to help them understand the needs of these young artists. For example, there may be clues to underlying issues that emerge under stress on the part of the student. In the past, a faculty member might have said: Well, that’s not my business. Now we hold annual workshops where they are trained to identify these problems. Or let’s say a student has a great intellectual curiosity that needs additional stimulation. We have a program with Columbia University where students can take courses that we could never offer at Juilliard – in the sciences, in mathematics, in foreign languages like Swahili, Arabic or Chinese. We also have an academic distinction program for undergraduates where they can stretch themselves intellectually by doing additional work, such as intensive research resulting in serious papers.

Is it possible, or desirable, for your students to get a full liberal arts degree in addition to a performing arts degree?

We provide a high level of liberal arts education for an undergraduate. Twenty-five percent of the courses of study are in liberal arts, which are based at Juilliard on the great books and a Socratic method of teaching. However, you cannot really expect to have the full impact of a conservatory experience and the full impact of a liberal arts experience at the same time. I wish one could. I’ve thought about it a great deal and pushed it as far as I could in that direction. But at the end of the day, in terms of sheer time management, when you have a pianist who needs to practice six to eight hours a day, you are not going to be able to ask that same person to also spend six to eight hours doing research in the library.

To approach this from a different angle, how do you encourage students to enlarge their view beyond music?

That is indeed an important issue. What we attempt to do is to stimulate the imagination of these young people and find out what directions they want to take, intellectually as well as artistically. And then we aim to nurture and mentor them so that they make progress in that direction. Our teachers in particular are really vigilant when it comes to identifying these interests.

Do you have a mentoring system in place?

Yes. We have a mentoring system in which students voluntarily work with a faculty mentor, and a high percentage of undergraduates take up this option. Generally we suggest that if you are a trombonist, for example, your mentor would be a dancer, so as to expand your horizons. This has worked quite well, especially when it comes to stimulating the imagination. In addition, comparatively recently we have developed four cross-currents in our curriculum that affect every single student in one way or another. These topics cover writing and speaking skills; information literacy and understanding how to use the Internet intelligently; technology in terms of how this relates to developing new work in drama, dance and music; and finally entrepreneurship: How do you think outside the box? This is extremely important, because young artists become so consumed with their work – with being effective as artists – that they can develop tunnel vision.

How do you choose your teachers?

Like at any educational institution, the faculty is the heart of this place. First of all, we obviously look at professional experience. But even if they are very famous performers – and we certainly have some of those – I want to make sure that they are dedicated teachers as well. Once all that is done, I look at them as people: What are they interested in and how are they going to be part of the community here? What do they want their students to achieve? If a teacher were to say to me, “I want my students to practice eight hours a day, I don’t want them to ever be involved in outside activities,” I would think twice about whether this is the right teacher for Juilliard.

You’ve often said that a quiet revolution is going on in education in the performing arts – at least as far as Juilliard is concerned – and that promoting this has been your goal.

When I came to Juilliard in 1984 – this is my 30th year as president – I very much wanted to change some key elements in the culture of the place. But I knew that to do it precipitously would be a mistake. I also didn’t want to call into question the basic mission of the school, which is to educate and train the next generation of dancers and musicians and actors. So I decided that it should be a revolution of sorts, but it should be quiet and gradual, and I think that’s actually what has taken place over the years.

What are the basic tenets of this revolution?

I ask our young artists to widen their horizons, to consider what their responsibility is off the stage, and to see how the arts can be nurtured, especially at a time when public support has become so weak. They should help anchor the arts in our educational system more firmly than is the case right now. And they should help the general public understand why the arts are an important part of the fabric of our society.

“We expect the highest level of artistic performance, but then we expect more.”

So, among other things, your students are trained to be cultural ambassadors for the arts?

This theme of the artist as citizen has become a very important part of the school. We expect the highest level of artistic performance, but then we expect more. We expect that, as effective advocates of the arts, our students understand how our world works and use that understanding to help the arts become a more important part of society.

What is the role and responsibility of the artist as citizen? And why is this so important?

The public sector has failed the classical arts. The National Endowment for the Arts hasn’t been a significant player in terms of revenue disbursal for a long time now, perhaps as far back as the Nixon administration. It seems to me that funding the arts is not even part of the political dialogue in any meaningful way. The arts have become sidelined, with no politician seeing any value in moving them forward in the face of such resistance. At the end of the day, with our educational system dropping the emphasis on the arts, I think we are reaping what we have sown.

How does a lack of support for the arts translate across a national culture?

It has a tragic effect on our educational system, which creates lasting repercussions. If you don’t know what the arts are, and you don’t experience them at some level of seriousness, you end up with mediocrity. As I’ve often said, mediocrity is like carbon monoxide. You can’t smell it, you can’t see it – it just kills you one day. That is what we have to fight against, and I don’t think America is doing a very good job of it. We are seeing new generations of leaders who have no relationship whatsoever to the power of the arts and their importance within our educational system and in our society.

The arts are often perceived as elitist and exclusionist, but they’re not. They’re for everyone. That is why having outreach – having a sense of responsibility as an art-ist, to be an advocate for the arts – is in my opinion an essential part of the education of an artist. And that is something we focus on at Juilliard.

What sort of outreach does Juilliard promote among its students?

Outreach for Juilliard can be a very powerful and multifaceted experience. We ask our students to leave their comfort zones. Instead of going to traditional venues, we encourage them to go into New York City public schools, into hospitals, hospices and nursing homes, and to perform there in an effective way. By effective, I mean that the program is designed in terms of duration, content, verbal explanation, and engagement, in such a way that the audience will benefit from the experience. This also has a major impact on the performer. For any artist, but for young artists in particular, seeing the power of their art on a non-traditional audience in non-traditional venues reveals to them how powerful the arts can be as a messenger of human values. The experience can really change these young artists, because when they go back to traditional venues, they think in a different way.

We also have students that travel all over the world – to places like Tanzania or Mexico or Brazil. And when they return, they have a higher energy level in terms of what they want to do as artists. They are much more motivated; they are much more focused; they have experienced how their art touches people in ways they didn’t expect. They really do understand that they can be powerful advocates for some of the best values of the human experience. That, I think, is very much a part of Juilliard.

So how do you see the relationship between the traditional focus on technique and this process of reaching out and communicating through performances?

When one starts educating young artists – in dance, drama, and music – the initial focus has always tended to be on technique. But technique is only the bridge to artistry. At its core, artistry is about communication. So if you get all the notes right or the steps right or the words right, that’s not art. That’s technique. And while you need technique in order to realize artistry, without the expressiveness and feeling for the need to communicate, you will not succeed as an artist.

The notes, the steps, the words are all there, but the soul of the performance is somehow lacking.

Exactly. When young people are first introduced to the Brahms Violin Concerto or Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, they find them such monumental mountains to climb, just in terms of realizing them technically, that sometimes, and I would say more than 50 percent of the time, the young performer will say: Gee, I did it! I was able to play all the notes! And of course, they have to realize that this is only one part of it. The other part is interpreting those notes and making the experience so very powerful.

“I hope we are perceived as a source of creativity and imagination – and of new work for new generations.“

To sum up, what exactly would you say that Juilliard – or maybe even the Juilliard brand – stands for?

I hope that Juilliard is perceived as an institution dedicated to excellence and to the future, and as a place that not only maintains the standards in the profession of drama, dance, and music but also enhances them. I hope we are perceived as a source of creativity and imagination – and of new work for new generations.

I think that, in America, tradition is not always as respected as it should be. Essentially, a place like Juilliard exists to maintain and enhance the traditions we have inherited and which a lot of people in this building deeply believe in and feel to be really important for the human experience. We ask our students to be leaders, to be communicators, to be teachers, and to make a difference – not to sit back and expect the world to come to them.

The interview with Joseph W. Polisi in New York was conducted by Ulrike Krause, THE FOCUS, and Alan D. Hilliker, Egon Zehnder, New York.

Joseph W. Polisi

Joseph Polisi was appointed President of the Juilliard School in 1984, when he was in his mid-30s. Prior to this, he was a dean at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and the Manhattan School of Music, as well as Executive Officer of the Yale University of Music. Polisi’s educational background includes music – he holds a Doctor of Musical Arts degree from Yale with a Masters in International Relations from Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. He has written two books: The Artist as Citizen advocating that performing artists act as cultural ambassadors to the world, while American Muse: The Life and Times of William Schuman is a biography of the American composer and former President of Juilliard. Like his father, who performed with the New York Philharmonic, Polisi is an accomplished bassoonist.

The Juilliard School

Founded in 1905 by Franz Liszt’s godson Frank Damrosch, The Juilliard School is a legend in the world of musical education. The school offers degree programs, from bachelor to doctorate, and has grown to include other art disciplines including dance and drama. In 1969, the school became part of Lincoln Center, considered by many to be America’s premier classical music venue. Admission to Juilliard is highly competitive, with an overall acceptance rate between five and eight percent.

PHOTOS: JÜRGEN FRANK