Competency and Potential

A Model for Private Equity Operating Partners

The battle cry of private equity, with clever financial engineering no longer a differentiator and much of the investable universe having shifted from mega deals to the middle market, is anchored in portfolio value creation. Operating partners, predictably, are rising to corresponding prominence.

Egon Zehnder has placed many such executives. Recognizing that the LP’s demands for excellence in portfolio operations will continue to increase – although not seldom without a nuanced perspective of what kinds of people and processes such excellence necessitates – we recently took stock of what we learned. We are delighted to present what we have learned.

Operating Partner Attributes

PE funds come in many shapes and sizes. Most like deals of a certain size; some prefer certain themes, such as consolidation or international expansion; others focus on distressed situations or corporate spin-outs. Some prefer control, others minority investments; specializations can run along multiple dimensions, such as geography and industry. Not surprisingly, the responsibilities of operating partners are correspondingly variable once we look past table stakes such as understanding cash flow management, performance dashboards and cost cutting. And while some funds involve their operating partners in activities such as deal sourcing and fund raising, the core task shared throughout this group of professionals is the hands-on involvement in existing portfolio companies. For that core task, which can be rooted in an industry (e.g. fast-moving consumer goods), geography (e.g. sub-Saharan Africa) or functional expertise (e.g. supply chain optimization), the general attributes of outstanding operating partners, irrespective of the particulars of their private equity firms, are:

Gumption: Getting stuff done, adding muscle where needed.

Accountability: Taking ownership of problems and their solutions.

Focus: Knowing what to ignore and what matters. Recognizing that the portfolio leadership team has finite bandwidth.

These attributes reflect the fact that operating partners are hired to accelerate value creation. But they are also bland and could describe the manager of a football team. We need a better model of the specific competencies that support these attributes.

Getting Specific: Leadership Competencies

Broadly speaking, these competencies come in two buckets. First, have they done it before? This is about hard skills and a track record of creating value in circumstances similar to those of the portfolio company. Second, can they get others to do it? This is about soft skills and knowing how to effect the desired change, i.e. working through others rather than personally leading.

“Effective operating partners are successful at translating between the fund and the portfolio. They know how to get focus on the key issues and influence both parties to deliver change that creates value.” (Connor Boden, Head of Portfolio Board Development at Advent International)

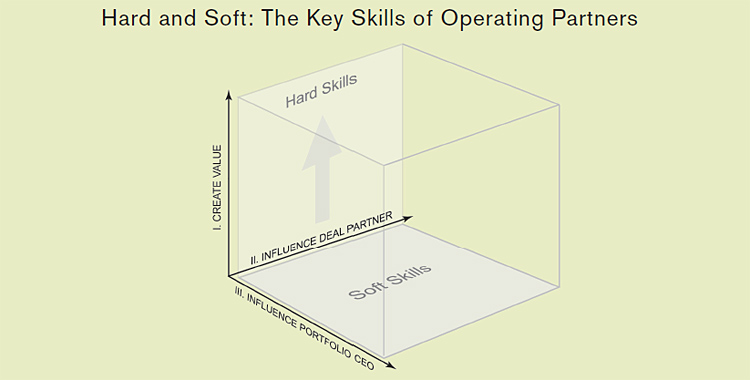

Using this delineation, we can map the effectiveness of operating partners along three different dimensions:

1. Create Value: This is why the operating partner is there; it’s the hard skill. It can be measured, both in project-based metrics (such as inventory turns) and, ultimately, in IRR. In terms of competencies, this dimension relates to commercial orientation and results orientation. The most effective candidates tend to be former CEOs with strong drive.

2. Influence the Deal Partner: The deal partner is a client. He or she needs to believe that the operating partner will, in fact, create value – and do so without putting off the management team. Influencing the deal partner is a soft skill rooted in speaking their language. In terms of competencies, this dimension relates to collaboration and influencing as well as market knowledge of PE (e.g. deal structuring, focus on cash flow). From the perspective of the deal team the potential mode of failure is “going native”, i.e. becoming part of and siding with the portfolio CEO. As a result, former conglomerate CFOs with experience overseeing groups of companies with relatively little shared infrastructure tend to be effective candidates.

3. Influence the Portfolio CEO: The CEO is also a client, albeit with different concerns. While he or she, too, needs to believe in the hard skills of the operating partner, they also will have to trust that their autonomy and influence will not be compromised. Influencing the CEO is a soft skill rooted in the ability to earn their trust. As one operating partner quipped: “You have one big gun with one big bullet: fire the CEO. But you want to avoid using that bullet at all costs … so you need to coach.” In terms of competencies, this dimension relates to collaboration and influencing as well as Change Leadership. From the perspective of the portfolio CEO, the potential mode of failure is either the operating partner’s inability to create value without usurping power or that of being “a spy for the fund”. As a result, former senior consultants who have gone on to business leadership roles tend to be effectiv e candidates.

These dimensions can be visualized as follows:

Highly effective operating partners, regardless of how they are used by the funds that employs them, function near the top end of all three dimensions.

“Having entered private equity on the operating side before becoming a general partner, I immediately recognized the power of deep portfolio relationships in driving value creation.” (Tom Scully, Partner at Welsh Carson)

The Operating Partner Bias

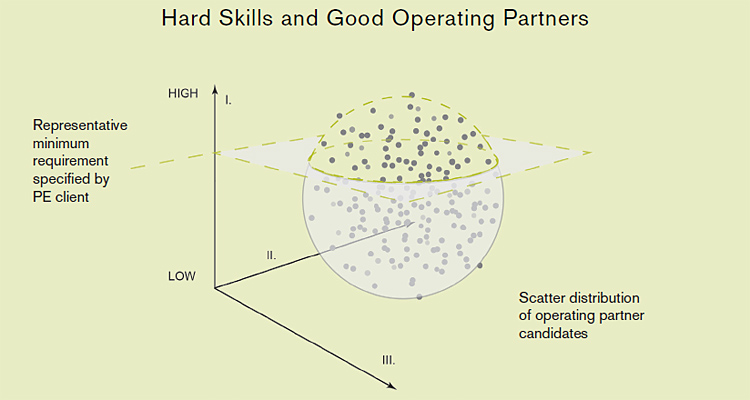

Many funds select operating partners with a primary focus on hard skills and the demonstrated ability to (personally) create value. As a result, the pool of potential candidates typically filters mostly on one dimension:

Limited partners have taken note. “We see the operating partner as someone providing PE firms another avenue into the company, another set of eyes,” says Rob Voeks, a partner at Private Advisors. “The challenge is that these executives must be positioned as tr usted advisors, not phantom operating partners on a list of names that helps raise money .” From the vantage point of his Fund of Funds, Voeks views this topic as a critical factor in the manager selection process, adding that “it would be a challenge for us to invest in a PE firm without some kind of operating partner model.”

“In the middle market, you have to get comfortable with limited resources and the limitations of management teams. The key is to carve out what matters most and get all eyes on that prize.” (Gary Matthews, Operating Partner at Morgan Stanley Private Equity)

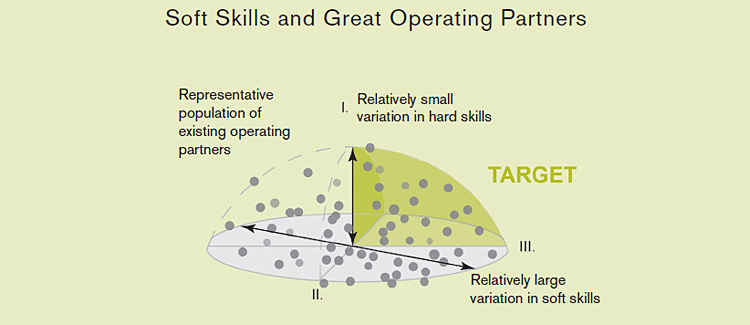

Another senior executive working for a state pension fund puts it more bluntly: “I don’t care if you’ve run a Fortune 50 company. If we don’t get specific examples of how operating partners engage with both the investment professionals and the portfolio companies – how they actually are ‘partners’ in the truest sense of the word – we walk away.” Although he asserts that such examples provide insight into “the what and the how of the operating partner approach”, he acknowledges that it is far easier to ascertain what operating partners are trying to do than how they are going about engaging portfolio management along the way. And indeed the relatively more rigorous focus on hard skills has given rise to a population of operating partners that varies most in its range of soft skills:

The question, therefore, is whether the approach to integrating operating expertise into the value creation mechanism of private equity can be improved further still. We believe that the answer, unequivocally, is yes.

From Good to Great : Leadership Potential

Fundamentally, the Operating Partner is the cartilage between the deal team and portfolio management. As one operating partner put it: “You have to be able to do a mix of things, often simultaneously. You may be coaching the CEO on process and style while mopping up after the deal guys, who focus on truth and fact.” It should not come as a surprise, therefore, that a substantive indicator stratifying the effectiveness of existing operating partners is their soft skill set.

Private equity funds are right, of course, to select only candidates who have the hard skill needed to create value. But this step alone often leads to sub-optimal solutions if not paired with a rigorous gauge of soft skills.

“It’s not enough for an operating partner to be smart and know the answers; to have impact you have to be able to build an effective network at the portfolio level.” (Andrew Rolfe, MD and Chairman of the Portfolio Committee, Towerbrook)

This is where leadership potential comes in. Think of competencies as demonstrated skills that can be verified in a behavioral interview. This is a powerful process, but in fact there are not many candidates who have had the opportunity to do everything in their past (just like there are few CEOs who were previously CFOs and consultants before that). So candidates that have the right hard skills, such as a career’s worth of supply chain expertise or CPG marketing experience in emerging markets, may not bring similarly demonstrable ability to lead organizational change or influence others – simply because they have not had the opportunity to do so.

Assessing the potential for soft skills is a powerful bridge for this dilemma. Think of potential as a metric for the speed with which candidates can build leadership competencies in both scale and scope – and in private equity that speed needs to be high. In the case of soft skills, this means further strengthening abilities such as collaborating and influencing, driving change and developing others. Knowing which traits link to the competencies can help deduce the root cause of not demonstrating the competencies in a behavioral interview. This root potential dimension, then, is the innateability to engage others – specifically engaging the emotions and logic of others to communicate a persuasive vision and connect individuals to the organization and the leader. The presence of such potential, which can be measured, uncovers candidates who may not yet had cause to develop their soft-skill competencies as much as their hard skills but are nevertheless capable of doing so in the right setting.

“Impact at the portfolio level can be built on projects or on relationships. Projects, such as working capital reduction, can be effective, but the real power of the operating partner is revealed when we coach CEOs with whom we have built strong relationships.” (Doron Grosman, Operating Partner at Court Square)

Implications for Private Equity

Private equity buys and sells companies. The days of leveraging aggressively and simply paying down debt to drive returns are gone, so value creation means changing the company itself. Although that can mean accelerating inventory turns, consolidating competitors or exploiting new target segments, these changes are inherently bounded. Increasing management quality at the portfolio level, on the other hand, is an unbounded change: it maximizes both the value of the company and the probability of continued value creation. And it relies on operating partners with the soft skills to engage, motivate and develop others.

“Building the trust with the entire management team so they are comfortable with an owner being on the team takes effort. You have to have the skills and invest the time in those relationships to truly create value. You and the CEO are really working for each other.” (Seth Brody, Operating Partner at Apax Partners)

Highly effective operating partners use their empathy to navigate and synthesize the concerns of the deal partner and the portfolio CEO: they know when to act and – equally importantly – when to listen. Having scratched the CEO itch, these candidates are keen to “play well with others”. Their potential reveals whether they can do so effectively. After all, many executives with demonstrated impact as agents of change and value creation when themselves in charge have not had to flex their soft skill muscle nearly as much as the hard skills that propelled their success.

Private equity funds that have advanced the furthest in their leveraging of operating partners recognize the impact of these soft skills on their returns. But knowing that soft skills add real value does not imply the capability of identifying and assessing either the corresponding competencies or the underlying potential. In addition, the pace of private equity necessitates the swift transition from ascertaining potential to its development into robust competencies since otherwise nothing is gained.

We believe that both of these steps – incisive assessment and accelerated development – are actionable and measurable; that they are eminently worth taking; that they will differentiate the best-performing private equity funds. The assessment and development of potential in soft skills is a powerful way for private equity funds to create more value – and greater returns – by ensuring that the operating partners they bring on will not only provide the know-how of what good looks like at the portfolio level, but also the right touch to deliver on that value.

Special thanks goes to co-author Christoph Lueneburger, formerly with Egon Zehnder (2008-2015).