Pushing back boundaries, making the seemingly impossible happen, coupled with that age-old human dream of flying – in the Solar Impulse aircraft hangar, ABB chief Ulrich Spiesshofer was able to see for himself the process by which a visionary idea becomes reality. Here, a team of hand-picked specialists is working on Solar Impulse, the first aircraft able to fly day and night powered by solar energy only. Piccard, from a famous dynasty of explorers and inventors, plans to fly round the world taking turns with André Borschberg in the single-seater cockpit. In their discussion about pioneering spirit and dealing with uncertainty, and in their shared enthusiasm for renewables – especially solar energy – the head of the international technology group and the initiator of a vibrant technology venture found a surprising degree of common ground. After the official conversation was over, both agreed that they should meet again before too long and continue their discussion – preferably, Piccard said, “between two and five every morning of this week,” when the pioneer will be found alone in his flight simulator for a 72-hour endurance exercise.

Ulrich Spiesshofer: Bertrand, you grew up in an exceptional environment. Your grandfather and father were famous inventors and pioneers for whom nothing was too high or too deep. How did this environment influence you? How should we imagine conversations at the Piccard family’s dinner table?

Bertrand Piccard: Throughout my childhood I heard the stories told by my father, my grandfather and all the people my father knew who came to visit us. There was Wernher von Braun, who came to our home several times, there were astronauts from the American Space Program, there were mountaineers, explorers, environmentalists, filmmakers. For me, the extraordinary was the normal state of affairs; I spent my entire childhood seeing how interesting life is when you leave certainties, dogmas, and paradigms behind. People like these were my only benchmark, so whenever I met people who were not like this I was really surprised. At first I thought they were the exception to the rule; when I realized that unfortunately most people are afraid of the unknown, afraid of change and uncertainty, it was a real shock for me! Yet as CEO of a global group like ABB you have to deal with uncertainty on a daily basis, too. I find it difficult to imagine any successful CEO in today’s world being afraid of uncertainty …

Spiesshofer: You’re absolutely right – but I think this has always been the case. Even in the past, running a big company and being responsible for many thousands of people and their families called for the ability to handle uncertainty. It’s true, though, that the nature of the uncertainty has changed. Today there is scarcely any long-term certainty in any economic sector – whether the factors involved are new materials and technologies, or the stability of the global economy and financial systems. Any good leader has to accept uncertainty as part of his or her daily life. This shouldn’t be something we fear but something we take responsibility for navigating through.

Piccard: Many people find it challenging to deal with uncertainty just in their personal lives – so creating a culture based on a fundamental willingness to work with uncertainty across a major organization takes this challenge to a whole new level.

Spiesshofer: Yet it’s so important that people feel at ease with uncertainty, at least those in leadership roles. If you’re clear about your course, about where you want to go, all the nervousness around uncertainty disappears. It is important to remain aware of your longer-term purpose, whatever turbulence you might encounter along the way. I think uncertainty can often generate responses that are more emotional than rational in nature. Take the case of Greece for example: When the Greek system nearly broke down, the whole world panicked. But Greece is tiny compared to the world economy! This was all about emotions, it was a knee-jerk response. Bertrand, I guess that when you’re up in the sky and you see heavy cloud or even a thunderstorm ahead, you don’t abandon your flight altogether – you simply adjust the controls to deal with the new situation.

Piccard: Exactly. But all too often we see leaders – especially in business – who dig in and resist technology change, until eventually their companies disappear altogether. These companies were led by people who believed the current situation would continue forever, people who didn’t use uncertainty as a navigational tool for their own leadership.

Spiesshofer: Yes – and this is something even ABB has had to learn. We had a near-death experience in 2002. There was one day in the last decade when the company was just hours away from bankruptcy. The reason was that basic rules had been neglected: The radar wasn’t properly monitored; and in fact the radar itself wasn’t good enough. Decisions had been taken that hadn’t been thought through, in terms of the consequences they would entail. Risks were taken – excessive risks, placing the entire business in jeopardy. The problem today is that many people in the company were so shell-shocked by that experience that now they don’t take risks at all. And this risk aversion is very dangerous for a company, too.

Working on a wing: With a wingspan greater than that of a 747 Jumbo Jet, the solar airplane gets some fine tuning at Dübendorf airport near Zurich.

Piccard: In fact the best opportunities lie in those moments of change! Without the ability to embrace questioning and doubt you’ll never create something new: You’ll merely stay within the limits of what you already know. Pioneering, in whatever field, is all about pushing the boundaries and handling uncertainty.

Spiesshofer: Perhaps this is why you and I share the same enthusiasm for solar energy. After the initial euphoria in this field, at the moment a sense of deep disenchantment has spread through the global solar energy economy. Yes, it’s true that the solar industry is currently in a very challenging situation: Many companies have gone bankrupt and more will follow. But that’s short-term noise. For me there is no doubt that in 30 years solar energy will play a key role in the global energy mix. This is why we acquired Power-One, the no. 2 for solar inverters – for a price that wouldn’t have been possible three years earlier. In the short term we might see business and market volatility, but in the long term we are gaining leadership in a key market. According to conventional management rules, we should have not done this deal. But looking at it from a leadership perspective, a major corporation with annual turnover of 40 billion euros can afford to invest 1 billion euros on this kind of venture.

Piccard: For me it’s important that you’re not just investing in renewables, but also focusing intensively on energy efficiency improvements. Combining the two is crucial – and a key concern in my projects, too. If we only invest in renewable energy production then with current levels of energy wastage we’ll never be able to produce enough solar energy, wind energy, biomass, geothermal energy, and hydroelectric power. We need to save energy: We need more efficient engines, better home insulation, better ways of transporting energy.

Spiesshofer: Our mission at ABB is to decouple economic growth from environmental pollution, to use less energy per unit of GDP and to produce that energy with renewable resources. In very simple terms that’s what we stand for. And if I’ve understood it correctly this is also precisely what you are seeking to demonstrate with your projects: That we really can run the world without consuming the earth.

“Any good leader has to accept uncertainty as part of his or her daily life. this shouldn’t be something we fear but something we take responsibility for navigating through.”

- Ulrich Spiesshofer

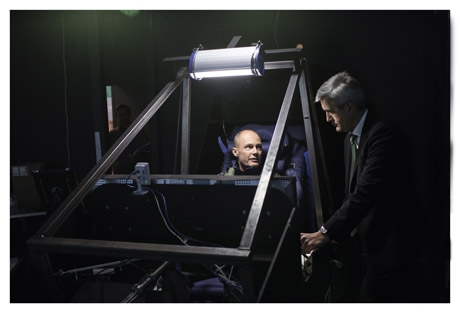

Simulated flight, real dialogue: The simulator features an exact replica of the Solar Impulse‘s cockpit, which measures just 3.8 cubic meters.

Piccard: So we make a good match: With our spectacular projects we’re making these technologies sexier and trendier for the general public, igniting the desire to use them. And you’re building and selling the technologies on an industrial level.

Spiesshofer: In order to get the world to where you and I probably want it to be, three things need to happen: Available technology, which is already economical and ecological, needs to be fully used. Politicians should play a key role: We need a predictable regulatory and legal framework that incentivizes investment in technology. Third, behavioral factors are very important – there’s a close connection between individual and institutional behaviors. Individual behavior is never based solely on cool reasoning – emotions always play a major role. You, Bertrand, are able to reach out to very large numbers of people on this emotional level – and this in turn can catalyze and motivate institutional behavior. We should consider working together: Together we could get things moving.

Piccard: Like you say, it’s not just about intelligent technology, it’s about human behavior, which is where my role as a psychiatrist comes in: Together, a psychiatrist and an engineer make a very powerful combination. We can produce the technical solution and motivate the people to use the solution at the same time. Imposing bans and lecturing people about how our lifestyle impacts the climate gets us precisely nowhere. If we present “protecting the environment” as something boring and expensive, nobody will do it! You have to win people over and reward them. If you want people to make a better future you have to give them an incentive: To be the one with the best electric car, the best insulated house, to be the company producing the most energy-efficient technology to cut your energy bills.

Spiesshofer: But “pushing boundaries” raises a question, too. How do you find the balance here: How do you push beyond the limit – without crashing and burning?

Piccard: I really don’t know if I do find a balance here, because I’m never happy with what I am or what I have! I always want more. I always want to improve things. I think it’s this inner restlessness that drives the pioneering spirit. If you’re happy with what you have, you stay within your box, within your boundaries. My dream was to fly around the world in a balloon. As soon as I’d done that I was thinking about what I wanted to do next – and had the idea of doing the same thing with no fuel on board. This is where Solar Impulse came from. Even after Solar Impulse I’m sure I won’t retire. There are so many other things to do. But ABB, of course, is a rather bigger venture than my hangar here …

Spiesshofer: That’s true, but the principle remains the same. When you’re running a business you need to retain a certain uneasiness, perhaps even paranoia, within the organization. You need always to be asking questions: What’s happening? What more can I do? Who’s coming up behind and in front of me? What opportunities are heading our way? Without this kind of pioneering leadership, ABB would not exist. If we were happy to follow the game we couldn’t sustain our business. Innovation is what justifies our presence in the market. It’s only by commercializing innovation, on an industrial scale, that we can afford to pay the people who work for us. At the same time we’re directly and indirectly responsible for half a million people. We have an enormous responsibility to not “bet the farm,” as they say. On the plus side, though, we have considerable room for maneuver within our system. If I put some portion of that capability to work on something really unusual, it doesn’t imbalance the overall center of gravity. Which is what we are doing more and more. We’ve set up a technology venture fund and in the last few years we’ve spent 150 million euros on future technologies ranging from wave energy to cybersecurity – including some very off-the-wall ideas. Yet this is balanced by the fact that we spend more than 1 billion euros each year in “classic” research and development. This overall balance seems sustainable to me.

“Setbacks often turn out to be lucky breaks when seen in retrospect.”

- Bertrand Piccard

Piccard: But how do you foster that spirit of uneasiness, how do you ensure that people don’t get stuck within their comfort zone? You may well have this spirit yourself – but how do you spread it around the whole company? This interests me – and not just as a psychiatrist!

Spiesshofer: One of our guiding principles is to avoid complacency. Good might not be good enough. Sometimes we take an external benchmark. Recently, for example, when one of our managers proudly reported that he had reduced the field failure rate for a particular product from 25 percent to 12 percent, we observed that if Boeing had a 12 percent failure rate he would be unlikely to get on one of their planes! We need credible external stimuli to drive change and self-scrutiny. At the same time I avoid pushing people too far out of their comfort zone as this can have the reverse effect, creating inhibition. We want to make sure that they question what they are doing. The questioning can come from an external benchmark or from internal cross-referencing – a strategy we use a lot.

Piccard: In our Solar Impulse project André and I ensure that everyone working here knows why they are doing what they are doing: We don’t just tell them what to do, we say what it’s for, as well. I’m not an engineer, so I can’t tell them how to make an electric motor. But if they know that the most efficient electric motor they can develop will help us build a solar airplane that will fly round the world, inspiring people with enthusiasm for new technology, then everybody in the team is motivated. This is about keeping your eyes on the bigger goal, too, and not just on the individual tasks that lead there. We’re not just gluing pieces of carbon together – we’re building the first ever solar plane that will be able to fly for five days and nights on end without using any fuel to cross oceans from one continent to the next. When we arrived in New York after the flight across America and were officially received by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, it was a proud moment for all of us.

“You have to aim higher and be prepared to fail. If you can’t deal with the possibility of failure you’ll never be a leader.”

- Ulrich Spiesshofer

Spiesshofer: As I see it, having a unifying purpose is crucial, in order to ignite passion. In your case this purpose is round-the-world flight; for us it’s “Power and Productivity for a Better World.”

Piccard: But it is difficult to find people who can enter into that spirit, and companies willing to support our work, because they often regard our ideas as unrealistic. So we don’t have any aircraft manufacturers or major energy companies involved: They don’t see the relevance.

Spiesshofer: Is this risk aversion on their part?

Piccard: I think it’s a lack of imagination.

Spiesshofer: Inertia is something I have to contend with a lot within ABB. Basically, many people feel they are paid to maintain the status quo. And yes, in a large company like ours there is definitely a certain amount of maintaining to be done – but even here there are ways of doing the job better day by day. My approach is that I want everyone to go home at the end of the day and ask themselves a simple question: What difference did I make today? It doesn’t matter if you’re cleaning the office or running a portfolio worth billions. There’s always room for improvement. I think that’s what makes people happy and motivated; running on the spot typically leads to a feeling of discontent.

When I travel around I try to meet people diagonally through the whole organization. Recently I met someone working in one of our factories and after I’d watched him working for a while I commented that this didn’t look like the most efficient way of working. He agreed, and suggested a better way of doing the job. When I asked why he hadn’t made this change before he said, “I was never asked.” I think this shows us a key element we need to introduce into large organizations: People need to feel that they can make an active contribution, that what they have to offer matters and is valued by their leaders.

“I can’t fly by simply flapping my hands: I can’t make the rules of physics change just because I want them to. But the limits we construct in our own minds, the limits we believe to be true – these limits have to be broken.”

- Bertrand Piccard

Piccard: One way we’ve made a difference at Solar Impulse is to have people who come from very different fields. We have people from Formula One, from shipyards, some from the world of aviation. When we couldn’t find an aircraft manufacturer to build our design, we subcontracted it to a shipyard instead, the company that built the Alinghi racing yacht. These people knew how to work with carbon fiber but not how to build an airplane – but combining their knowledge with the expertise on our team has produced fabulous results.

Spiesshofer: Many books and articles describe how diversity improves innovation and performance; how getting people to think in different ways leads to better solutions. But in practice we often find that it’s difficult to make that diversity work, to get people from diverse backgrounds really working together towards a common goal.

Piccard: I admit that this isn’t easy, even in our small team. At Solar Impulse we’ve solved the problem by introducing a dual leadership paradigm. There’s André Borschberg and there’s me: He’s an engineer, I’m a psychiatrist; he’s a jet fighter pilot, I’m an explorer. Together we cover a very large range of expertise, embodying the synergy we want the others to find. They see and understand the way we work together; they understand, too, that it isn’t always easy.

Spiesshofer: As CEO of a major group my role is like that of an orchestra conductor, bringing all the various instruments together in harmony so that they play the right piece of music to the right audience. My job is to assemble teams designed for specific purposes. If the aim is to improve day-to-day productivity, that calls for a particular team. If the task is to assemble the next generation of mobile phones, we need different people on board: In this case we needed to call in a neurosurgeon with expertise in micropositioning equipment. Recently we called in some insurance mathematicians to work with our engineers, helping us to develop a fantastic range of new service products. We have thousands of different ideas and projects in hand: The skill is to understand what capabilities each team needs to fulfill its purpose, and to bring in the right people – sometimes individuals with very different areas of experience who can complement an existing team. There is an element of risk here, of course – it doesn’t always work!

Piccard: If you always succeed first time, if everybody agrees with you and everybody believes in you, it means you’re not being ambitious enough.

Spiesshofer: Sure, you have to aim higher and be prepared to fail. If you can’t deal with the possibility of failure you’ll never be a leader. I recently tasked a team with developing a power electronics device – for capturing the Chinese market – at 50 percent of current cost. They said it couldn’t be done.

Piccard: That’s precisely the kind of answer I would see as a challenge.

Spiesshofer: That’s just how I saw it. We gave the team 12 million euros a year and asked them to work on it. I believed a solution was possible and I believed in the team. And you know what? We’re launching the product now. Of course there were setbacks along the way – involving considerable cost, too – but ultimately the team was successful because it developed an entirely new design for this particular product. My guiding principle is that I want to have a company where mistakes are allowed, where we learn from those mistakes and from each other. A challenge at ABB is that many of our people currently have a fixed idea about what’s allowed and what’s not allowed in terms of risk taking. I want to push that boundary whilst never betting the company overall.

Piccard: Often setbacks turn out to be lucky breaks when seen in retrospect. Take the main spar on Solar Impulse, for example, this big piece in the middle of the wing: It took eight months and about 40 people to design and build it, 64 times it went into the oven to bake the polymers, and then we did a final load test and it broke! Just like that – with a very loud crack. We had to postpone the round-the-world flight by a whole year: 2015 instead of 2014. Was that a setback? It depends on how you see it. The advantage was that in 2013, instead of testing the new plane, André and I had nothing to do on the operational side. The engineers had to rebuild that part but we weren’t involved. So we decided to cross the United States. This was a dream we’d had, but hadn’t been able to fit into the program. And it turned out to be our biggest success with Solar Impulse to date! We had the support of all the various officials, administrations and airports; we had Ban Ki-moon welcoming us in New York. We had a huge amount of global media coverage – paving the way for our round-the-world flight – and it was a great way to prepare our team, too.

“If you always succeed first time, if everybody agrees with you and everybody believes in you, it means you’re not being ambitious enough.”

- Bertrand Piccard

Spiesshofer: Do you have a particular personal mental technique for dealing with setbacks in a positive way?

Piccard: I keep my mind and my heart open, and I keep my life and my future open. You need to be open, ready to seize opportunities, or be willing where appropriate to accept failure and be flexible enough to change course. When I was 24, I launched a microlight airplane company. I wanted to have two-seater microlights with pilots in tourist spots all over the world, to take tourists on sightseeing trips. It was a complete failure! I didn’t get the necessary permits and the project never got off the ground. Is this a setback, is it a failure? Personally, I would simply call it an experience.

Spiesshofer: My childhood wasn’t characterized by as exciting projects as yours but I’m reminded here of my grandfather’s favorite saying. “And tomorrow the sun rises again,” he used to say. If we can take this attitude to life – less self-important, more confident – we can contemplate the whole concept of failure and success in a much more relaxed way. Though of course we all have boundaries we have to observe, too.

Piccard: Absolutely. I can’t fly by simply flapping my hands: I can’t make the rules of physics change just because I want them to. But the limits we construct in our own minds, the limits we believe to be true – these limits have to be broken. Even if you think you can’t do it, you have to try. Maybe you’ll succeed after all.

Solar Impulse, as it glided over San Francisco in preparation for the cross-country flight in 2013.

Spiesshofer: At ABB we have two non-negotiable conditions: One is operational health and safety – nobody should be risking their life to serve our customers – and the second is integrity. I don’t want any unethical behavior in the company. These are the two conditions where I won’t allow any compromises. In your case, by taking your explorations to the extreme you might well risk injuries or even fatalities – involving yourself and perhaps others, too.

Piccard: We talk about this a lot. For example, before we took off for the round-the-world balloon flight, my partner Brian Jones and I discussed what risks we were prepared to accept. We decided to accept the risk of breaking a leg or an arm, of being cold or hot, or hungry, but we would not accept the risk of serious spinal injury or death. So had we encountered a severe thunderstorm – even just before the finish line – we would have abandoned the flight altogether.

Spiesshofer: I think this is a crucial point. In our case it is important that people know where our boundary lines are drawn. They can be sure that when they come to work at ABB they won’t be risking their health. They will be treated ethically and they will be required to treat others the same way. Many other things are negotiable, and we can talk about those. But these things are non-negotiable.

Piccard: So this is less about limits and more about clearly defining the rules of engagement, defining acceptable and unacceptable behaviors. Although we’ve been talking about technology and enterprise here, basically we’re also talking about life in general. People have challenges and tasks to fulfill day after day: sending their children to school, finding food and water, learning, getting a job, finding a wife or a husband. All of which call for exactly the same spirit as the tasks we’ve been talking about. This is why Solar Impulse is not just a technology project for me – it also brings me back to my role as a psychiatrist. People often come to thank us – for inspiring them, giving them hope, showing them a new way of thinking. For me this is the very best reward we can have.

In the hangar that houses the Solar Impulse at Dübendorf airfield near Zürich, the dialogue between Bertrand Piccard and Ulrich Spiesshofer was facilitated by Gaëlle Boix, Egon Zehnder Geneva, and Philippe Hertig, Egon Zehnder Zurich.

Ulrich Spiesshofer

was born in 1964 and studied economics and engineering in Stuttgart, where he received a doctorate in economics in 1991. He then worked for almost 15 years with consulting firms, initially at A.T. Kearney and later at Roland Berger. In 2005 he took up an appointment as EVP Head Corporate Development, including group strategy, M & A, operational excellence, and supply chain management. This Swiss power and automation technology group was formed in 1988 through the merger of the Swedish company ASEA with Brown, Boveri & Cie. (BBC) of Switzerland; the organization underwent a very difficult phase in the early 2000s. Today the group is active worldwide, has sales of around 40 billion US dollars and numbers approximately 145,000 employees in 100 countries. In addition to developing and implementing corporate strategy, Spiesshofer was also responsible for formulating the group’s acquisition strategy and establishing a venture fund for promising technology companies. In 2009 Spiesshofer was appointed Head of the Discrete Automation and Motion Division. Under his leadership, the division’s sales doubled. He successfully managed the integration of the US company Baldor – the largest acquisition in ABB’s history. Spiesshofer initiated a targeted expansion plan that enabled his division to grow its market share, develop new business fields such as electromobility and uninterrupted power supply, and improve its geographic coverage. The acquisition of Power-One, based in the US, has established ABB as a leading supplier of solar inverters. On 15 September 2013, as announced earlier in the year, Spiesshofer succeeded Joe Hogan as ABB’s CEO. Aside from his extensive responsibilities at ABB, Spiesshofer’s life revolves around his family. Together with his wife Nathalie and their two sons aged 11 and 15 he lives in Zollikon on Lake Zurich, where Spiesshofer – a keen sailor – owns a boat. Spiesshofer is an avid skier and also an all-round musician: He plays the clarinet, saxophone, and accordion.

Bertrand Piccard,

born in 1958, belongs to a famous family: In 1932, his grandfather, Auguste Piccard, was the first to ascend into the stratosphere and see the curvature of the earth in a balloon. His father, the marine explorer Jacques Piccard, was the first to reach the deepest point of the ocean and set a world deep-sea descent record of 10,916 meters below sea level in the Mariana Trench, in the bathyscaphe “Trieste” that his father had invented. In 1999, together with Brian Jones, Bertrand Piccard completed the first non-stop round-the-world flight in a hot-air balloon. At age 16, Bertrand Piccard already numbered among the European pioneers of hang-gliding and ultralight flight, exploring all aspects of aviation: distance, altitude, aerobatics, powered flight, hang-gliders and parachutes. Piccard has been the European champion in aerobatics, held the world altitude record and attained several other world firsts: He was the first to cross the Alps in an ultralight aircraft, for example. However, one aspect of flight fascinated him even more than records and adventure, and that was the study of human behavior and the various levels of consciousness in extreme situations. He studied medicine and psychiatry, working as a senior physician at Lausanne University Hospital before opening his own private psychotherapy practice. Following a family tradition that combines scientific exploration, protection of the environment and the search for a better quality of life, Piccard’s current project, Solar Impulse, involves a round-the-world flight in a solar-powered aircraft together with his partner André Borschberg. In 2012, Piccard was named as a United Nations “Champion of the Earth,” and was described in the citation as follows: “A pioneer, explorer and an innovator who operates outside the customary certainties and stereotypes, Dr. Piccard is first and foremost a visionary and a communicator. … As initiator of Solar Impulse, he has developed the project’s avant-garde philosophy and defined its symbolic reach in order to convince governments to launch much more ambitious energy policies.” Together with Brian Jones, Piccard established the Winds of Hope Foundation, which works to combat forgotten diseases like noma in Africa. Piccard is married, has three daughters and lives near Lausanne.

PHOTOGRAPHY: MATTHIAS ZIEGLER

Nachfolge gestalten

Nachfolge gestalten

Governance voranbringen

Governance voranbringen

Führungspersönlichkeiten entdecken

Führungspersönlichkeiten entdecken

Leadership entwickeln

Leadership entwickeln