Leading Chinese Cross-Cultural Acquisitions

A Practical Guide for Chairs and CEOs

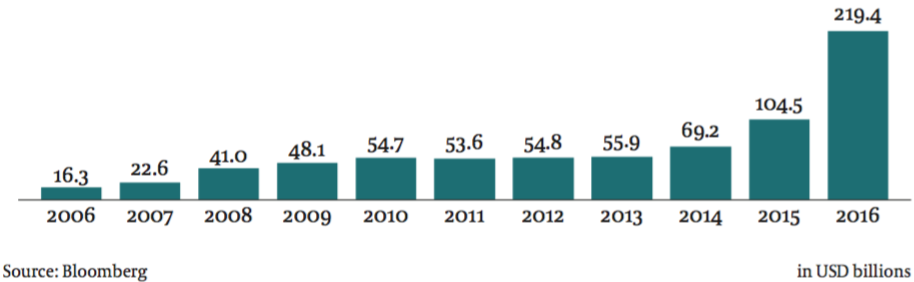

The marked increase in Chinese acquisitions of Western industrial firms is a natural consequence of China’s emergence onto the global economic stage. Like other newly developed economic powers past and present, China seeks to build enterprises that extend beyond its borders.

Total volume of China's overseas deals

However, studies suggest that more than 50 percent of acquisitions fail to add value – and it is safe to assume that the odds for Chinese acquisitions of Western companies are even worse, given the lack of experience each side has with the other in this set of roles. The rewards of success and the cost of failure for all involved make it imperative to have a cleareyed view of the dynamics at work in these transactions and a framework for mitigating risks.

It is important to appreciate the extent to which Chinese companies are attempting to accelerate the traditional path to establishing multinational corporations. China began its export phase in earnest at the beginning of this century, when the country shifted from exporting low-value goods like toys and clothing to establishing itself as the contract manufacturer for much of the developed world. It then sought to evolve its multinational presence by exporting its own high-value goods, such as industrial machinery and consumer durables. But there are few examples of these types of Chinese products succeeding in Western markets. The occasional attempt by a Chinese company to establish greenfield operations in the West has similarly failed to gain traction.

The West, it seems, will buy phones but not capital goods – or even engineered parts – made in China. Part of the reason has been that the life cycle cost of Chinese investment goods isn’t as competitive as it needs to be. But there also is the problem of perception. Countries, like companies, have a brand image, and China’s is still stuck in an earlier time when it was heavily associated with low-value goods and was unable to manufacture capital goods to Western standards.

China is not the first country to be faced with this branding challenge. Fifty years ago, Japan was in the same position. The West greeted Japan’s entry into the global auto market with bemused puzzlement: Who would buy a car from Japan instead of from a Western automotive manufacturer? Japan’s response was simply to persevere. The quality of its products steadily improved – so much so that Western companies now adopt the Toyota Manufacturing System as the benchmark for quality. Today, there are Japanese auto plants across North America and Europe, and Nissan and Renault share a Brazilian-born CEO. Japan’s economy thus has become truly multinational.

China could take the same path as Japan, but given the pace of business today and the options China has from its capital reserves, doing so is not very attractive. Instead, China is attempting to leap over the high-value export and greenfield steps entirely and to create multinational corporations through acquisition of established Western businesses. But when a company in one country sets out to acquire an enterprise in another, it usually does so only after having built considerable operating or cross-cultural experience in that country. China, however, does not have that kind of knowledge about Western countries upon which to draw. And without having made itself a familiar presence in the West, China’s moves are seen as shrouded in mystery and regarded with suspicion. So a Singaporean company buying a French shipbuilder would be viewed as a natural part of the globalization of the economy. But if a Chinese company (and especially one that is state-owned) seeks to do the same, the assumption is that the Chinese are targeting the West’s intellectual property.

Leveling an uneven field

To the Chinese acquirer, this state of affairs is unfair. But there is a bigger problem to solve. Because there is no history of Chinese presence in the West and because there are few examples of senior Western executives who have successfully advanced their career by working for a Chinese firm, it can be notably difficult for Chinese owners to attract and retain top Western talent once an acquisition has taken place. Indeed, many Western executives consider such a move to be a career derailer.

This has profound implications for Chinese firms acquiring Western companies. Without exceptional – and exceptionally motivated – leadership to drive the integration process and manage the post-merger entity, the chances for success are slim. In this way, Chinese-driven M&A deals are no different from a combination between two Western firms.

Lessening the talent management challenges faced by Chinese firms in the West is a substantial task and cannot be taken on all at once. Instead, it is more manageable to first tackle what must be done in the short term to maximize the chances for success for transactions currently under way and then to examine separately the changes in perspective that will take longer to implement.

Guidance for boards on facilitating post-transaction success

To understand what makes for a successful industrial transaction when the acquiring company is from China, members of the Egon Zehnder Industrial Practice held extensive, confidential conversations with the CEOs of Chinese and Western industrial companies that have been involved in such transactions. These conversations painted a consistent picture of what is required:

- Nourish a strong bond at the top. Building bonds between the two companies and moving forward to a shared future starts with a solid relationship between the two CEOs, who need to genuinely respect and trust each other. If getting to that point requires one side to make more effort to, say, get on a plane for additional face time and unstructured interaction, so be it. A number of the CEOs with whom we spoke mentioned the importance of having an accomplished and neutral translator but noted that even the best translator will not be able to fully overcome the Western inclination to view translation as a barrier to personal connection.

- Start with a clean slate. When a Chinese enterprise acquires a Western company, the tendency has been to let the Western company continue as a standalone entity, retaining its original management. Both sides are doing themselves a disservice, however, if they assume from the start that this is the optimal structure. History shows there are a range of successful post-merger possibilities: Sony treats Columbia Pictures as a standalone entity; GE fully integrates the companies it acquires; and Danaher keeps its acquisitions as distinct companies but under the umbrella of uniform management processes. So it is that questions of structure, staffing and incentives need to be addressed with a clean slate, in which the costs and benefits of each option are analyzed and measured against company strategy.

- Make the board of directors a strategic asset. Chinese acquirers need to remember that, generally speaking, Western boards have considerably more power than do Chinese boards. In fact, not only can a board effectively safeguard the owners’ investment, but it also can act as an important source of guidance for company management. To do so, however, the board must be composed of a balance of owner representatives and independent CEOs and senior executives from other enterprises. Constructing a board with the right range of experiences and perspectives can go a long way toward setting the post-acquisition entity on a solid footing. A commitment to corporate governance best practices will make it easier to attract experienced, respected board members at a time when competition for directors is high. Where the final post-acquisition structure doesn’t include a formal, statutory board of directors, establishing an advisory board can be an effective alternative.

- Know what you don’t know. It’s natural for people to respond to uncertainty by filling in gaps in their knowledge with assumptions or outdated information. A Westerner whose company is being acquired by a Chinese firm may think that the two years he spent at a Western multinational in Shanghai a decade ago means that he “knows China”; likewise, the Chinese may assume that the person from their side who speaks the most colloquial English and has had the most cultural exposure to the West is the person who will be the best choice to oversee the transaction. Faulty assumptions like these can undermine the process of building a strong foundation for managing the acquired company.

- Be transparent in decision-making. Bringing together two groups of people who have limited knowledge of each other can be a recipe for mistrust if essential information flows only through pre-established relationships or comes from lower-level messengers rather than decision-makers. Both Chinese and Western leadership need to work to counter this, expending extra effort to be transparent about decision- making and to communicate throughout the organization.

- Be sensitive about technology transfer. It pays to be especially diligent in thinking about how to defuse what is a hot-button issue for the West. One Western CEO with whom we spoke told of how a Chinese acquirer paid licensing fees to his company after the acquisition. Doing so was a symbolic gesture, of course, but precisely because it was symbolic, it was effective in reducing suspicion. The transfer was more effective and structured as well because it was done through mixed teams in the context of a defined project.

- Be strategic about compensation and incentives. Rightly or wrongly, in the eyes of many Western leaders, taking a position at a company that has been acquired by the Chinese carries a high-risk profile similar to a Silicon Valley startup. Those digital ventures generally include equity that vests with time or performance milestones as part of compensation packages. Chinese acquirers should take the same approach, aggressively using compensation and equity, including options and phantom equity, as part of the talent management strategy.

- Build a new culture. An acquisition results in a new entity that needs its own culture – simply hoping two cultures can continue side by side under the same roof rarely works. Establish joint project teams and substantial long-term rotation programs between the acquired company and Chinese headquarters to demystify both sides by building relationships and humanizing the process. Send Western executives to China and Chinese executives to the Western company to reinforce the bilateral nature of the transaction rather than making it seem that one side is taking over the other. Chinese executives who have spent time at a successful multinational also can act as authoritative cross-cultural bridge-builders.

- Leverage collective strengths. With all the challenges a Chinese-Western merger faces, it’s easy to overlook the positives that drove the transaction in the first place. Both sides should combine their networks, markets and resources to identify and achieve tangible successes to strengthen internal support and build excitement and commitment.

A commitment to fundamental change

These nine steps will go a long way toward mitigating the most significant post-transaction leadership risks faced by Chinese acquisitions and to providing a foundation from which the acquired company can move forward and achieve its potential. Taking the time to build this strong basis is critical; early missteps can be difficult to rectify later. In the long term, however, the goal should be to address the factors that give rise to those risks in the first place. Both sides need to make a commitment to evolve their perspective.

Chinese acquirers should ensure that they are approaching talent management and leadership development in a way that draws from global best practices. It is possible, when a company is in the export phase, to view the process of production as being the primary means of value creation, with the executives, managers and front-line employees there to serve that process. But at the level at which the Chinese are now playing, it is people, not processes, that represent the key company resource. Some of the talent management and leadership development best practices to be considered include:

- Creating succession plans for the CEO and other key leaders

- Establishing assessment and development programs aligned with the changing needs of the company

- Using merit-based promotion tied to clear metrics and behaviors

- Developing networks to connect with top-tier leaders outside the company

- Monitoring and managing the firm’s reputation in the talent marketplace

The extent to which Chinese acquirers will be successful in the West depends, in large part, on their ability to adapt to a talent marketplace in which every executive – including those currently employed – is a free agent motivated not just by compensation but by the opportunity to solve meaningful problems, work autonomously with quality colleagues and have access to career paths that reach to the executive committee.

In a similar vein, Chinese acquirers will find themselves in a much stronger long-term position if they focus more on developing competencies than merely acquiring assets. Take the most visible example: Intellectual property has a shelf life – and one that tends to shrink amidst today’s continuous innovation. More important than the patents alone is maintaining a corporate culture that fosters innovation and generates a pipeline of new patents. This requires having leaders who can delegate responsibility to teams and give them space to create while still meeting deadlines and requirements. This is very different from the prevailing model in China, in which most of the key decisions are made at the top of the organization. What makes for a successful board chair in China may produce a bottleneck for organizational growth in the West.

Finally, Chinese acquirers must embrace their role as active, strategic owners. Combining two companies almost always results in opportunities for efficiencies, synergies and scale. Sidestepping these possibilities is to bypass the real fruits of acquisition. In approaching ownership more fully, Chinese acquirers will find it beneficial to expand their competencies in finance, engineering, manufacturing and product development. Eventually, they will want to tackle P&L and customer-facing functions as well.

The West, for its part, must accept that the global stage has another major player on it. It makes perfect sense, at this point in China’s trajectory, that its companies should seek to globalize; Chinese enterprises are driven by the same strategic logic as Western companies when establishing a footprint in the economy of another country. To be sure, Chinese firms currently tend to be driven more by revenue than shareholder value, but that may well change over time.

The West also must move past its default position of independence at any cost – hardly a recipe for post-merger success. Instead, Western companies that are acquired by Chinese firms should see the transaction for what it is: a historic opportunity to have an impact on the direction and perspective of a global economic power. China is more than ready to learn from the West in the areas where the West has advantages, such as the ability to create and sustain innovative organizations. In the process, Western executives may end up encouraging Chinese business in the adoption of many of the qualities that Westerners feel are essential, but in a way that aligns with the Chinese perspective.

In the end, an evolution of thinking on both sides holds the potential for significant value creation. In many ways, the strengths of China and the West are complementary. China brings access to its vast market, capital, expertise in rapid scaling and the power of a long-term perspective. The West is defined by its process and best practice orientation and the ability to institutionalize innovation and to manage profitability. Like the best mergers, the business future of these two powerful cultures lies in combining their qualities. From our current vantage point, we cannot yet know what that combination would look like. But it is incumbent upon both China and the West to work together to chart that path.