Cultivating inner awareness, unlocking hidden capacities

By Scott London

Founded a half-century ago on a new vision of human possibility, the Esalen Institute helped spawn avant-garde ideas and practices that have moved into the mainstream. Today the center is building off that legacy by preparing a new generation for the challenges of twenty-first century leadership.

Tucked away on an isolated stretch of California’s majestic Big Sur Coast about halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, the Esalen Institute has been at the forefront of the human potential movement for over half a century. The ideas and practices that came out of Esalen in the 1960s and ’70s have influenced the cultural conversation on a wide range of fronts, from science and health to psychology and education. They have shaped how we think about relationships, what we eat, how we pray, and how we search for meaning and direction in our lives. It hardly seems surprising that the series finale of Mad Men (aired May 2015), which just aired this spring, would depict its main character undergoing a personal breakthrough in an Esalen-like workshop set on the picturesque cliffs of Big Sur.

Today many of Esalen’s programs focus on personal growth and self-development, just as they did a half-century ago. But the institute has broadened its focus and directed more of its resources and energies to social responsibility, conscious leadership, and how to engage and transform pressing global issues.

“Our mission has always emphasized both personal development and social transformation,” says Esalen’s president Gordon Wheeler. “But we haven’t always been good at putting those together. We’ve done that in a more intentional way over the last ten years.”

Esalen’s CEO Tricia McEntee stresses that there has been an intentional shift at the institute “from me to we” in recent years. The mission of Esalen is to serve the world, she says, not be a refuge from it. “I think there is a sense of urgency to take our personal growth out into the world to make positive change.”

Nothing exemplifies this outward shift more than the institute’s focus on leadership development. Esalen’s Integral Leadership Program, now in its fourth year, is aimed at inspiring and supporting the next generation of conscious leaders. The month-long certificate program explores a range of conscious leadership skills critical in today’s world. They include emotional intelligence, ecological awareness, cross-cultural communication, conflict resolution, and self-expression.

George Kohlrieser, an organizational psychologist and author who has been leading workshops at Esalen since 1976, says the program is not aimed at teaching traditional leadership skills so much as learning to lead yourself. As he sees it, that is something many leaders are not very good at. “If you’re not leading yourself, how are you going to lead others, and how do you expect them to trust you enough to follow?”

The program is experiential by design. Students learn to communicate effectively, deal with conflict, and cultivate emotional insight and awareness. The emotional component is critical, Kohlrieser says. “I find that many leaders are confused on this question. There is a tendency to think that if you show emotions, you’re a weak leader. But unless you can understand and harness the power of your feelings in every aspect of your work, you’re more likely to alienate people than to inspire them.”

Part of the program’s appeal is that it combines traditional coursework in conscious leadership with a residential immersion experience. That includes daily movement classes, group awareness workshops, presentations by guest speakers, access to Esalen’s famous hot springs, and work in the kitchen, the cabins, the farm and garden, or one of the other departments.

The Integral Leadership Program is not so much a departure from Esalen’s original mission as a natural extension of it. When Michael Murphy and Richard Price, two charismatic Stanford University graduates, founded the institute in 1962, their goal was to create a place where people could explore and develop their latent human capacities. Inspired by William James, Aldous Huxley, Teilhard de Chardin, and other champions of human possibility, they created a new kind of learning center, one devoted to self-development through practices that brought together mind, body, heart, and spirit.

Within a few short years, Esalen had become not just a flourishing institute but a leading laboratory of the human potential movement. Groundbreaking thinkers, artists, psychologists, scientists, and philosophers came to Esalen to teach, among them historian Arnold Toynbee, psychologist Fritz Perls, mythologist Joseph Campbell, philosopher Alan Watts, theologian Paul Tillich, and two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling.

There were seminars and lectures on a seemingly endless variety of subjects, many of them edgy, offbeat, and ahead of their time. On any given week there were lectures on East-meets-West spirituality, Gestalt therapy sessions, Rolfing classes, encounter groups, permaculture intensives, yoga training, and workshops on Reiki and other forms of healing.

Over the past half-century, the spirit of exploration and experimentation has evolved. The heady days of the 1960s and ’70s, when Esalen was at the crossroads of the counterculture, have given way to a more low-key, reflective, and communal atmosphere. Today the institute offers more than 500 programs a year and continues to explore innovative and boundary- spanning ideas, techniques, and practices for cultivating a more complete life.

Gordon Wheeler has been leading the Esalen Institute, either as CEO or as president, for the past 13 years. A distinguished clinical psychologist and the author of several books on Gestalt psychology, he has spent much of his career consulting with organizations on strategic planning, values clarification, and mission development. These skills were crucial in restructuring Esalen’s internal organization about a decade ago as well as in strengthening the institute’s overall commitment to public service.

When I meet Wheeler on a warm afternoon in March, I’m struck immediately by his easy charm and calm, unhurried demeanor. The conversation ranges freely and he seems equally at ease discussing psychological concepts, models of education, and the latest trends in management – often skipping between them to illustrate or drive home a point. “Leadership training is a multibillion dollar industry around the world now,” he tells me. “What’s behind the explosion of leadership education, I believe, is the sheer complexity of the world today. Everything is interconnected and every problem has multiple dimensions. It can be overwhelming.”

Where do we find leaders who can grapple with this kind of complexity? Wheeler says we need leaders with a high degree of self-awareness and self-mastery. The Integral Leadership Program tries to cultivate that by giving young leaders an intensive, interdisciplinary experience, one that brings together personal development, emotional connection, somatics, social and group intelligence, and lifelong learning.

By integral leadership, Wheeler means an approach that integrates multiple dimensions of the self – heart, mind, body, spirit, and relationships with others. “These are all aspects of our whole self; they can’t be cut off from each other,” he says. “When you develop each of those capacities, they interplay and allow you to deal with complexity more effectively.”

Relationships are a vital component – not an add-on, but an integral part of the curriculum. “Relationships are a crucial dimension of being human,” he insists. “It’s part of who you are from birth. Our brains are formed by relationships. They are hard-wired, particularly in the first year of life, through relational patterning. We’ve got to capture that whole integral vision in the training curriculum for leaders.”

Compared with the curricula at major business schools and leadership institutes, this approach may seem unconventional, even radical. But Wheeler says it is consistent with practices that have been taught at Esalen since the 1960s – long before leadership development became the watchword it is today.

“Fifty years ago,” says Wheeler, “the whole idea of lifelong personal growth – the kind that integrates cognitive, emotional, and social development – wasn’t there.” That is changing. The fact that so many corporations, universities, and government agencies are sending their leaders to training programs today shows that an academic education alone does not go far enough in preparing people for the demands of twenty-first century leadership.

We need leaders today with a high degree of self-awareness and self-mastery.

At 84, Esalen’s co-founder Michael Murphy is no longer active in running the institute’s day-to-day operations. But as chairman emeritus of the board and director of Esalen’s Center for Theory and Research, Murphy is still very much a presence at the institute. When I visit him at his home in Mill Valley, just north of San Francisco, he greets me with the hearty enthusiasm and easy wit for which he is well known.

Esalen has grown and matured over the past half-century, but Murphy stresses that its animating mission remains essentially the same – to nurture our highest human capacities and to “broaden the repertoire” of education by actively engaging mind, body, emotions, and spirit. “All of us can cultivate these hidden human reserves,” he insists. “You don’t have to be a prodigy or a genius, by common standards. We’re all coiled springs.”

In retrospect, he finds that a lot of the radical ideas that came through Esalen in the 1960s and ’70s have now been absorbed into the cultural mainstream. Take yoga, for example. “There were probably about 20 yoga studios in America when we started Esalen. Now there are 20,000.” The same can be said of somatics – movement-based therapies like Rolfing, Feldenkrais, and the Alexander Method. “There was no field of somatics back then. Now everybody I know has had some bodywork or other.”

One of the more surprising developments today, he finds, is the growing popularity of mindfulness. Rooted in the tradition of Buddhist meditation, the practice has spread through the culture like wildfire. Mindfulness training is now as common in the executive suite and the athletic facility as it is at the retreat center. Oftentimes mindfulness is used as a means of stress-reduction rather than spiritual awakening. But even in its more watered-down forms, he feels that mindfulness represents a real evolutionary leap in the culture.

Some of the ideas and practices taken up in the early years of Esalen were failures, Murphy now admits. “But that’s true with all evolutionary experiments. Only a tiny percentage actually work. That’s okay. The universe is an experiment, a cosmic jazz band.” The spirit of experimentation is still alive and well at Esalen, but there has been a lot of “winnowing” in the public programs, he says. “A lot of lessons were learned through the mistakes.”

These lessons are a mark of how the institute has evolved. “People always assume that evolution implies linear progress,” he says, “but that’s a mistake. Evolution is never linear. It meanders more than it progresses. If you look at our culture, you can see that it’s always evolving. But along some lines it hasn’t progressed. Along others, it has regressed, or simply plateaued.” This is why experimentation is so vital to any organization – it opens up new pathways to growth when others lead astray or turn back on themselves.

It is somewhat ironic that Murphy has become an influential voice among management philosophers and leadership experts. Ironic because he does not profess to understand the corporate world, yet is an astute and successful businessman. Ironic, too, because he has steadfastly refused to play the guru role, yet has become recognized as one of the pioneers of the human potential movement.

Asked what advice he has for young leaders today, Murphy leans back in his chair and pauses for a moment. “I think you always have to build with your strengths and go to your calling,” he says pensively. “The question is, what turns you on? You can always develop the skills you’re short on. But sometimes, in developing those, you thwart other parts of yourself. What I’ve come to realize is that it’s better to fail in your own dharma than to succeed in somebody else’s.”

The idea of finding and following your inner calling was central to the work of Abraham Maslow, the humanistic psychologist and close friend of Murphy’s who taught at Esalen in the early years. Instead of focusing on the neurotics favored by traditional psychologists, Maslow studied peak performers – those who had attained a measure of what he called “self-actualization.” One of his enduring findings was that self-actualized individuals are motivated by something larger than themselves. They become mission-driven.

Murphy says this impulse is reflected in the proliferation of nonprofits and NGOs today – organizations that serve some pressing social need or public good. In the United States alone, there are now half a million nonprofits operating in the public interest. “The majority of them are little mom-and-pop operations – organizations of just a few people. But what an array of leaders!”

Authentic leaders are guided from within. They take their cues from some purpose larger than themselves.

What this suggests is that authentic leaders are guided from within. They take their cues from some purpose or problem outside themselves. The implications of this for leadership development are profound, because it means that any training not aimed at cultivating inner awareness and unlocking our hidden capacities is limited in its usefulness.

While there are other leadership institutes and business schools teaching integral leadership today, Michael Murphy and Gordon Wheeler both say the program is unique in bringing together so many different aspects of who and what we are. “Of course it has the intellectual learning components,” Wheeler says, “but it has these other dimensions as well.”

“There are some fabulous organizations training people to do cross-cultural, cross-boundary, peacemaking work,” he observes. “But when I ask the people who are training leaders about the embodied dimension, which is so central to learning and empathic attunement, they say, ‘Well, we don’t know how to put that in our training program – that’s what we come to Esalen for.’ So, we’ve developed a program that puts that in.”

George Kohlrieser sees it as a unique alternative to more traditional leadership programs and business schools where you have to “respect the boundaries,” as he puts it. Esalen creates a safe space to step out of your comfort zone and take risks. “I don’t know of any other place in the world that offers students the same opportunities to open themselves.”

As Wheeler sees it, Esalen has always sought to push boundaries and explore new frontiers. The goal of the leadership program, he says, is not to replicate what other schools and programs are doing, but rather to broaden the training available to young leaders by spanning multiple disciplines of modes of understanding. “We are one small institute on the cliff on the edge of the western world. Our niche at Esalen is looking for the next thing, and helping it emerge.”

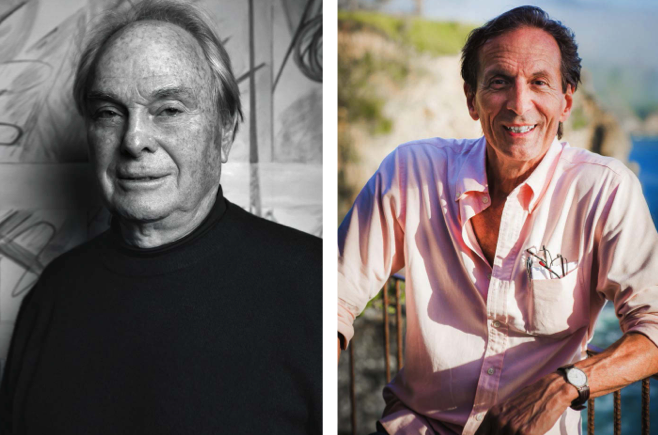

Michael Murphy (left) co-founded the Esalen Institute in 1962. Today the organization is led by president Gordon Wheeler (right).

Scott London

Scott London is a California-based journalist, photographer, and radio presenter.

PHOTOS: SCOTT LONDON