Skeptics may consider family businesses outdated due to a perceived lack of rationality. However, these businesses have proven both successful and enduring—provided their owners understand how to leverage specific advantages and manage disadvantages effectively.

Family businesses require a tailor-made governance system that accommodates their unique complexities. Ultimately, their success and survival depend on a shared vision based on common values among family members.

The Landscape of Family Businesses

Family businesses are widespread and successful, distinguished by their continuity and closed inner workings. They often perplex professionals who view them as irrational, as they do not adhere to traditional business logic. As Dan Ariely puts it, sometimes the irrational is “predictably irrational.” [1]

The family aspect begins when the entrepreneur realizes that their “baby,” the business, is evolving due to the arrival of a first child. This moment marks a pivotal decision: whether the business should transition into a family firm.

There are numerous pros and cons to consider.

The Disadvantages of Family Businesses

To start with the downsides, transforming a first-generation business into a family-owned entity can limit the firm's discretion.

Family businesses often rely on a dominant family influence, which constrains opportunities for capital leverage. Across the globe, especially outside market-oriented countries like the UK and USA, families maintain a dominant ownership share to secure control.

This trend is especially pronounced in privately owned companies, which represent the majority of family businesses worldwide. In fast-growing, capital-intensive sectors such as biotechnology and IT, family ownership can hinder growth opportunities.

The Benefits of Keeping Family in the Family Businesses

On the positive side, converting a first-generation business into a family business can open up long-term perspectives.

When viewed as a family business, the firm's focus shifts from fiscal year concerns to a generational outlook. This takes numerous factors into consideration, including:

1. Merging Stakeholder and Shareholder Perspectives

The implications of this change are manifold. First, stakeholder and shareholder perspectives merge. Under a one-year framework, stakeholders often face conflicting goals—growth versus payout, investment versus immediate profits, sustainability versus profit maximization. However, when entrepreneurs begin to consider a 30-year horizon, the needs of employees, customers, the local community, and owners tend to align. To secure the long-term survival of the firm, management must meet the needs of all stakeholders equally.

2. Evaluating Innovative Activities

With this long-term perspective, owners assess innovative activities and investment projects differently. The cost of capital is generally lower in family businesses, and there is less pressure for annual or quarterly returns. This allows family businesses to invest in projects that may only yield returns after several years, supporting both radical innovations and incremental improvements.

3. Risk Aversion

At the same time, family business owners must be inherently risk-averse. They cannot jeopardize the existence of the family business, which rules out high-risk ventures—even those with only a marginal chance of occurring. Should such risks materialize, the company's continuity would be at stake.

4. Shared Values

Feuding family members can lead to the downfall of the family firm. From the Buddenbrooks to the Gucci family, there are numerous tales of relatives fighting until the business collapses. This paradox underscores that family can be both a strength and a weakness.

A healthy family business is rooted in shared values and norms, which are vital for the firm's survival. During the first two generations, these values typically stem from the founder's personality, becoming deeply embedded in the corporate culture. Norms originating from the founder's values and behaviors are passed down through stories, rituals, and guidelines.

How to Maintain a Competitive Advantage for Your Family Business

When common values and norms are effectively transmitted, later generations continue to share a value base, giving the family firm a competitive edge. For instance, consider the Merck family of Merck Darmstadt, who discussed a potential merger with Ernesto Bertarelli, then owner of Serono, a family-controlled biotechnology firm.

When Bertarelli asked when negotiations could begin, Jon Baumhauer of Merck replied “immediately,” surprising Bertarelli and his adviser. [2]

Baumhauer's rapid action was based on six months of family discussions, with over 150 family members involved and no information leaking to the market.

How to Navigate the Challenges of Family Business Growth

As family businesses age and the owner group becomes more heterogeneous, the risk of entropy increases unless countered by shared values and norms.

Even without open conflict, divergent intentions and latent conflicts can create opportunities for outsiders to exploit. This phenomenon, termed “expropriation of family business owners by outsiders,” [3] signifies a dramatic loss of influence for the family firm.

The Shift from Emotional to Financial Cohesion

Expropriation often starts with a power vacuum within the owner family, rooted in a lack of shared values and conflicting visions. Over the years, the cohesion of the family can shift from emotional ties to a more financial-based unity. [4]

Family businesses held by extended families, or cousin consortiums, face diversity challenges, including varying ages, cultural backgrounds, and professional experiences, compounded by poor communication. Dispersion and disinterest are significant threats to older business families.

Ensuring Family Business Survival

Consider Rupert Murdoch's attempt to take over Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal in 2006/07. Legally, his chances were negligible, as ownership was organized in trusts governed by the uninterested senior generation. Instead, he strategically approached the younger generation, perceived at the time as powerless.

In private conversations, Murdoch questioned the fairness of the senior generation withholding ownership rights from the younger members.

By urging the younger generation to pressure their parents for a sale, he ultimately succeeded.

The Bancroft family, previous owners of Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal, agreed to allow a 27-year-old opera singer, a family member chosen by Murdoch, to join the board. Without the power vacuum within the Bancroft family, the absence of shared values, and the resulting lack of communication and trust, Murdoch would have had no chance of success.

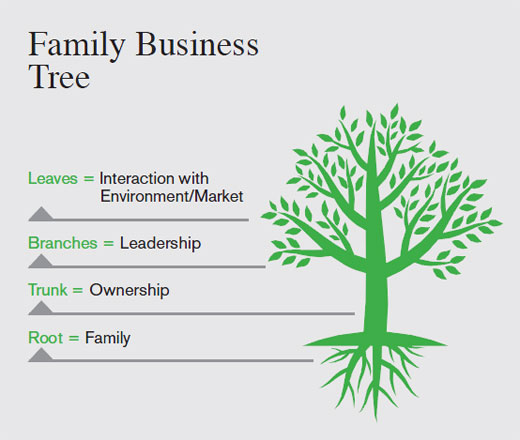

The Family Tree Metaphor for Addressing Survival Challenges

Describing the family business as a tree helps illustrate the survival challenges faced by these businesses. The leaves and the environment must correspond or else the tree will suffer a premature death.

Here’s what we mean by this:

Roots: The Foundation of Family Values

The roots of the family business symbolize the family itself. They represent the shared values, traditions, and norms that ground the business. Just as roots provide essential nutrients and stability to a tree, the family's collective identity and vision underpin the firm’s success. Healthy roots enable the family to navigate challenges and maintain cohesion, fostering resilience during turbulent times and growing when the time is right.

When family values are strong and well-communicated, they create a robust foundation that supports the business through generations.

Trunk: The Strength of Ownership

The trunk embodies ownership, serving as the central support structure that connects the roots to the branches. It represents the family's control over the business and the decisions that guide its current and future direction. A strong trunk ensures stability and resilience, allowing the business to withstand external pressures.

Ownership dynamics are crucial; as families expand and generations pass, maintaining clarity in ownership roles and responsibilities becomes essential.

A well-defined ownership structure enables effective decision-making and empowers family members to collaborate towards common goals.

Branches: Leadership in Action

The branches of the tree symbolize leadership, extending outward to represent the diverse management and strategic initiatives within the family business. Just as branches reach toward the sky, effective leadership drives the firm’s growth and innovation. Strong leadership fosters an environment where family members can express their ideas and contribute to the business's vision. It also enables the firm to adapt to changing market conditions and seize new opportunities.

Leaders must be capable of nurturing relationships both within the family and with external stakeholders to ensure the business's continued success.

Leaves: Interaction with the Environment

The leaves represent the family business's interaction with its environment and the market. They symbolize how the firm responds to external factors such as customer needs, market trends, and competitive pressures. Healthy leaves signify an organization that is vibrant and responsive, able to adapt its strategies based on feedback from its surroundings. This interaction is vital for growth, as it allows the business to innovate, improve, and remain relevant in a dynamic marketplace.

Good Nutrition for a Healthy Family Business Tree

The long-term perspective of family businesses increases their dependence on “good nutrition.” Healthy roots are needed to provide the firm with a vision grounded in shared values. Only then will the trunk develop the stability and strength necessary to support leadership. This foundation enables the family firm to meet market demands and proactively shape future markets.

Everything is interconnected – if one part of the tree suffers, all other parts are deeply affected.

How to Build a Governance System for Family Businesses

Governance in family businesses is inherently complex due to the interplay between family and business. When designing governance processes, the unique characteristics of the family must be considered. A guiding principle states that the complexity of a family firm’s governance system should match the complexity of the family business system, which consists of four subsystems: family, ownership, leadership, and market operations. [5]

The Role of Trust in Family Governance

Trust plays a vital role in moderating these relationships. Complexity arises from the number of family members and their differences in age, location, experience, and professional training. Differences in expectations can significantly increase complexity.

Family businesses, governed by owners related by blood or marriage, spend more time together than owners of other types of companies. This proximity creates opportunities to build trust, reducing the need for complex governance mechanisms. Family businesses with high trust levels typically have lower governance costs.

Tailoring Governance to Family Needs

Governing a complex family necessitates a customized system of processes, including:

- Rules of membership: Who qualifies as “family” and what value should they add?

- Rules of representation: Who speaks for the family, and how are representatives elected?

- Rules of compensation: Do family members not involved in the business receive compensation for their contributions?

The Merck Family Example

For instance, the Merck family has an intriguing board election system. Out of roughly 150 owners, any family member elected by a majority of their peers secures a seat on the family representative board, with each member allowed to vote for up to ten representatives. This process fosters communication and mutual awareness within the family ownership group.

How to Manage Complexity During Family Business Succession

The complexity of governance can significantly change during succession in early generations. For example, a manager who owns 100% of the voting shares and has four children may face a dramatic increase in complexity if ownership is divided equally. If the former owner-manager does not plan for this situation by establishing an outside board or drafting buy-sell agreements, the governance system may no longer match the new ownership structure.

Solutions to Complexity

To cope with this situation, there are two possible solutions:

Draft a governance system that anticipates increased complexity before succession.

Transfer ownership of the business to only one child.

Explore our guide to succession planning for family businesses here.

The Dual Nature of Family Businesses

Governance in family businesses presents challenges that surpass those faced by non-family businesses. Family businesses generally either outperform their non-family counterparts or fail dramatically. They require professional managers who understand complexity and long-term advantages, as well as family owners who grasp the dynamics of expropriation and family values.

When both non-family executives and family owners recognize these powerful forces, the family business can maximize its performance and unique competitive advantages.

Meet our team of family business advisors here.

1 Dan Ariely (2008). Predictably irrational – The hidden forces that shape our decisions. HarperCollins: London

2 The new Merck: Beating the odds. IM D Case 3-2137

3 Klein, S.B. & Decker, C. (2011). The sale of the family firm: A holistic alternative. Paper accepted at the Academy of Management Entrepreneurship Division. San Antonio 2011

4 Pieper, T.M. (2007). Mechanisms to assure long term family business survival: A study of the dynamics of cohesion in multigenerational family business families. Peter Lang Verlag: Frankfurt

5 Klein, S.B. (2009). Das Komplexitätstheorem der Corporate Governance in Familienunternehmen. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaftslehre Special Issue 2/2009: 63-82

RESUMÉ Prof. Dr. Sabine B. Klein

Prof. Dr. Sabine B. Klein holds the INTES Endowed Chair of Family Business at WHU (Otto Beisheim School of Management) in Koblenz/Vallendar. A third-generation family business member, she was Professor of Strategy and Family Business at the European Business School in Wiesbaden until 2009. She is a founding member and past President of the International Family Enterprise Research Academy (ifera).

RESUMÉ Prof. John L. Ward, Ph.D.

Prof. John L. Ward, Ph.D., teaches and conducts research on strategic management, leadership and continuity in family businesses. A Professor and Co-Director of the Center for Family Enterprises at the Kellogg School of Management in Evanston, Ward has written several publications on family business. He is a graduate of the Northwestern University (B.A.) and Stanford (M.B.A. and Ph.D.).