A handful of companies deliver high profits and grow above their industry average. These high-performance companies got where they are not by chance but by choice. Their leaders consciously decided to create a high-performance culture and put in place the elements required to get there. It’s not easy, and few companies are in that league. Here is how they do it.

By definition, most companies deliver average profit margins. A few, however, deliver operating profit margins that are 50 percent-150 percent above the industry average. Even fewer also grow well above the industry average — they take market share and maximize profits simultaneously. They enjoy superior growth, increasing profitability, better utilizing capital and, therefore, escalating market capitalization. What accounts for the difference between these high performers and the great mass of middling companies? The exceptional companies maintain a high-performance culture that drives everything they do.

Many companies claim to have a high-performance culture, but the reality is that very few do. As a result, not many people actually have experienced such an environment. The difference between the culture of even a very good company and a genuine high-performance culture can be a shock. A top executive of a high-performance company says of the difference, “Previously, I ran a billion-dollar business for one of the world’s most respected companies, but even that experience didn’t fully prepare me for the intensity of a true high-performance culture. What I subsequently discovered is that a year in a good company is like a month in my current company, where work is a full-contact sport, not touch football.”

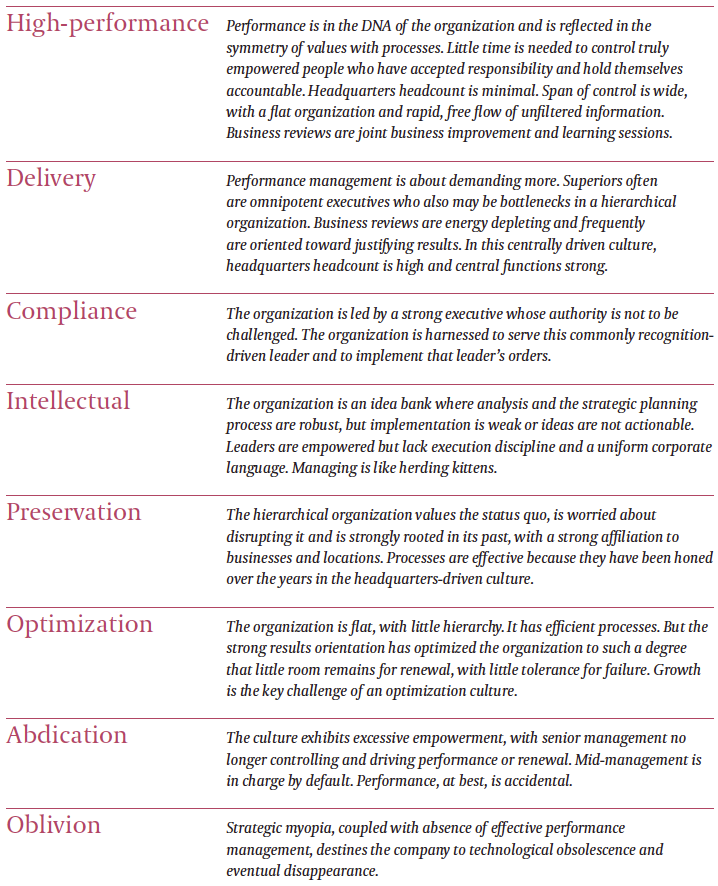

The relentless nature of a high-performance culture makes people who do not understand it uneasy. Not surprisingly, many executives and companies feel comfortable where they are — bound by past policies, practices, conventional wisdom and settled expectations. In the machinery industry, for example, a 10 percent operating profit margin appears to constitute acceptable performance to many companies, yet outliers deliver margins of more than 20 percent.

It doesn’t have to be that way, as the top performer depicted in Figure 1 demonstrates. A board and management can consciously choose to create a high-performance culture — regardless of the past, the competition or the industry. That doesn’t mean that a high-performance culture can be ordered up overnight or simply copied from a successful company. Painstakingly establishing such a culture can take a decade — and requires a lot of courage, commitment and resources. This kind of culture cannot be created in the abstract but only in the concrete, where it is manifested in how the organization’s values are implemented, how management systems and incentive programs operate, and the way employees behave in practice. Through our research and experience working with high-performance companies, we have found that they consistently do the following:

-

Adhere to a performance ethic that combines the ambition to do the unthinkable and the discipline to deliver the nearly impossible

-

Exercise a passion for renewal in the business, the organization and its people

-

Liberate leaders to get on with the business of the company

These are not abstract principles. They are practices and deeply engrained behaviors in the daily life of the organization that have concrete consequences for the business. And they are practices that any company can choose to adopt, but they must be accompanied by an in-depth, long-term commitment.

The Ethic – and Ethics – of Performance

High-performance companies adhere to an ethic that is manifest along two critical dimensions: ambition and execution. These companies set targets at levels generally seen as unachievable and execute with relentless discipline others may see as neurotic. This performance ethic (singular) is grounded in a widely shared set of ethics (plural) — deeply held values that drive what otherwise might be mechanical, political, superficial or random approaches to target setting and execution.

“Impossible is just a big word thrown around by small men who find it easier to live in the world they’ve been given than to explore the power they have to change it. Impossible is not a fact — it’s an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration — it’s a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.”

Muhammad Ali

Setting almost unthinkably high-performance targets requires both courage and outsized aspiration. Disciplined execution requires commitment, conscientiousness and a willingness to take personal responsibility, as well as tools and processes to make sure results are not left to chance. And the acceptance — without resignation or scapegoating — of inevitable shortfalls that occur when targets are set out of reach requires trust.

In their processes, policies and operations, these high performers typically do the following:

-

Set transformational targets in revenue, costs and margin: For example, one leading company that has outgrown its competitors in size and outperforms them year after year sets goals of reducing product costs by 7 percent over a rolling two-year period while boosting product benefits by the same amount. If that goal were achieved, then, in just a few years, the compounded savings and benefits offered to its customers would reach astronomical levels. But even if the company is unable to maintain that pace, the scale of the ambition encourages people to think big, to refuse to settle.

-

Pursue systematic and relentless execution: Ambitious targets must be accompanied by the discipline to do what it takes to come as close as possible to reach them. From operational strategy to manufacturing capability and plant productivity, outperformers use continuous improvement to slash cycle times and increase yield, capacity and reliability and achieve quantum leaps in quality, efficiency and cost reduction. While most companies do this, intensity and rigor set high-performance companies apart. They focus on process control — not quality control. Their focus on flawless processes that are converted into execution muscle on the first iteration renders quality control and rework practically unnecessary.

-

Adopt only a few measurements, carefully balanced: High-performance companies look for growth and cost leadership. For one high-performance company, the key metrics are top-line growth and margin expansion and so are working capital improvement and return on newly invested capital. Why? Because they are important indicators of operational excellence. Customer care is measured by the timeliness and quality of delivery on commitments. Leadership effectiveness is measured by employee retention and the internal fill rate for open positions. Another company empowers its leaders to balance the short and the long-term by rewarding managers after they have improved the previous year’s results by 5 percent. Ten percent of any profit above that initial 5 percent is allocated to the management bonus pool.

-

Undo the budgetary straitjacket: Many companies view budgets as commitments to be delivered no matter what and, therefore, treat them as targets for incentive compensation. This widespread practice produces a number of performance-limiting effects. First, tying incentives to the budget encourages people to understate their projections for their businesses so they can easily attain their incentive targets. Second, the coupling of incentives and budget discourages people from blowing past their targets for fear the boss will set higher targets following a year of such unforeseen success. Consequently, people try to avoid greatly exceeding their targets — targets that have been understated in the first place. In these budget-focused cultures, the core managerial competence is sandbagging — making decisions to deliver the budget at the expense of longer-term sustainability. And organizations that try to avoid this dilemma by setting unreasonably high incentive targets tied to the budget are at risk of demotivating their people.

Contrast that practice with the practice of a $10 billion company that is a high performer in its industry. The company has abolished the straitjacket of annual budgeting as a non-value adding activity. It concluded that spending a significant amount of energy on an internal process that delivers a number that will not be right — unless it is managed to be right — in a year’s time is a waste of shareholder value. The company now runs rolling quarterly and 12-month forecasting processes instead of budgets.

Another high performer, which has grown its market capitalization in excess of tenfold to more than $50 billion in just over 10 years, establishes budgets and targets, but it sets them so high that they generally cannot be reached. However, no one is penalized for missing the targets. As an executive from the company puts it, “Failure to deliver the impossible still produces a miracle.”

Still another high performer rewards for progress along a roadmap to outperformance. Depending on the business unit, the route along that map may vary from cost transformation to market share to global scale, but the typical measurements are growth, margin expansion and cash flow.

Such organizations free their people to deliver maximum performance without the concern for what it means to their annual bonuses or their career. They do not follow a 12-month or even quarterly cycle with the budget as a sacrosanct contract. Instead, the cycle could be a week or a day. To them, performance is a way of daily life.

High performance does not happen accidentally. Outperformers consciously aim high and just as consciously tolerate failure as the cost of achieving comparative success against their competitors. Yet they deploy countermeasures quickly if results fall short. They do not rely on markets and cycles to bail them out. They know that consistently seeking to avoid failure inhibits initiative and discourages the risk-taking that is essential for breakthrough results. They also know that aiming high is futile in the absence of disciplined execution, operational excellence and continuous improvement.

Pursuing a Passion for Renewal

A strong performance ethic will generate superior results, but ambitious targets and disciplined execution, by themselves, do not produce the renewal, continual learning and innovation required to stay ahead of changes in technology, competition and markets. In genuinely high-performance cultures, a strong performance ethic is complemented by a passion for renewing the business in order to keep it viable and vibrant. Organizations that have a passion for renewal exhibit these characteristics:

-

Organizational humility. Management has the collective humility to forthrightly admit what it does not know, an attitude that is reinforced by insistence on fact-based (as opposed to belief-based) decision making. Leaders are committed to organizational learning as an antidote to the complacency that outperforming their peers could breed. In fact, they maintain a healthy insecurity about other industry players. As one executive puts it, he and his colleagues are “constantly miserable” about where they stand against the competition, even when far ahead. And to continue to outperform and outflank their rivals, they are eager to learn new things from whatever source — people at every level of the organization, competitors and other industries.

-

Commitment to innovation. Companies that remain satisfied with merely doing more and better of the same thing are ripe for disruption — or takeover. By contrast, companies with a passion for renewal not only pursue innovation in order to disrupt their industry, but they also are willing to disrupt themselves, whether by cannibalizing their products and services or transforming their business models. While such a commitment may lower profits in the short term, high performers regard superior products and services as the only sustainable path for staying ahead of the competition. Innovation-driven growth allows them to streamline the company and lead change before it leads them.

-

Desire to seek or create new niches. Many companies explain outperformance by competitors as a result of the good niches the outperformers occupy. But outperformers do not come to occupy those niches by accident. They move into, or create, new niches by instituting internal processes or by acquiring companies where there are clear margin expansion and growth opportunities that can be exploited through the acquirer’s performance ethic. And they exit from poor niches, leaving them for competitors.

-

Ability to add value through acquisitions. High-performance cultures are good at adding value through acquisitions because the acquisition is infused with their own culture. One high-performance company is so good at this that it does not need to justify its acquisitions to the capital markets. Further, to deeply understand what has been bought, the company sends a member of its top leadership team — and sometimes even the CEO —to manage an acquisition for the first 12 to 18 months.

The combination of humility, openness to learning, and the restless desire to create additional value through innovation and acquisitions enables high performers to take measured risks. They neither gamble the company on high-stakes rolls of the dice — as poor performers may do hoping to make a step change — nor shy away from making a bold move when the facts favor it — as complacent or risk-averse cultures do. Instead, they continually renew the business both incrementally and, when the opportunity arises, dramatically. Because they are process driven, even the passion for renewal is a process.

Liberating Leadership

The command and control approach to performance management exerts pressure on management to deliver on commitments — no less and, typically, no more. Further, the control process takes a considerable amount of internal business review time and energy without necessarily adding to organizational muscle. The more time that is spent on control and review, the less time that is left for execution. By contrast, high-performance companies liberate their leaders and their organizations to get on with the business. They minimize internal processes and normally operate clear P&Ls, often virtual organizations, so people can focus on what really matters. There is clarity about responsibility, authority and accountability. In their approach to leadership, they generally do the following:

-

Align talent management with the right cultural attributes. Because so few people have experienced high-performance cultures, high-performance companies invest an unusual amount of senior management time and energy in talent management. In hiring, they employ rigorous, uncompromising assessment to determine whether a candidate will thrive on the intensity and relentlessness that goes with the territory or wilt in an atmosphere that can be extremely uncomfortable for people who cannot adapt to it. Once the right fit is ascertained, they take risks by giving real responsibility to executives. But they mitigate risk through exceptionally strong training programs, even in the upper tiers of management. In one high-performance company, for example, an executive appointed to head a $500 million business unit found himself shadowing other successful executives for months before being allowed to take charge.

High-performance companies make sure that executives are culturally ready for bigger assignments — creating a robust pipeline of leaders who are self-motivated and self-guided. At the same time, these leaders retain the humility that is essential for collaborating with colleagues and remaining open to learning and renewal. In one prominent high-performance company, the executive team spends up to six weeks teaching in the organization’s “leadership university.” Is that a wasteful misuse of these top executives’ valuable time? “No,” says an executive in the company. “I put in that time today so that tomorrow I don’t have to spend far more time managing, controlling and correcting people.” This is process control applied to management bench strength.

High-performance companies also deal quickly with toxic employees, like ego-driven, would-be “stars,” who undermine the culture. Non-performers, who simply cannot keep pace with their more dynamic colleagues, are similarly dealt with. As the CEO of a prominent high-performance industrial company says, “Accepting non-performance is not fair to those who do perform.” The sports world often employs a similar approach to performance management. Sir Alex Ferguson, the longtime coach of Manchester United, let go of even the biggest stars if they undermined the culture and the team’s performance. -

Achieve large spans of control through cultural and operational symmetry. This is a litmus test for a culture and its leaders. In the hierarchical organizations of days past, spans of control sometimes were as narrow as four or five direct reports. In high-performance cultures, however, executives usually have more than 10 direct reports and sometimes as many as 20. This is possible because self-guided, collaborative leaders do not need to be pushed, only channeled in line with the organization’s specific business objectives. These large spans of control flatten the organization and enable information to circulate quickly and decisions to be made expeditiously. Empowerment is granted where it has the most impact, and such empowerment often is reflected in small headquarters size.

-

Make fact-based decisions. Many leaders would say they are making fact-based decisions when, in reality, their decisions are governed by organizational constraints on the business that are assumed to be unchallengeable. Other leaders pride themselves on their gut feel or instinct when it comes to making decisions. Intuition when informed by experience no doubt has its merits; but in high-performance cultures, leaders rely on facts — regardless of what traditional beliefs of the organization they might call into question or what their gut tells them.

-

Practice root-cause analysis. When problems arise, leaders in high-performance cultures drill down to the root cause of issues — transparently and in a spirit of objective inquiry based on years of experience and deep industry expertise. They, above all, are problem solvers. They are not looking to fix blame and, thereby, incentivize people to cover up problems. They are there to help, creating a trusting and genuinely collaborative culture. As one executive puts it, “If you keep it, it is your problem. If you share it, it is our problem.”

-

Favor leaders who balance strategic orientation with attention to detail. In high-performance cultures, leaders are highly strategic, but they also are able to operate and add value at the root-cause level. Even if they do not know the answer to an issue, they know who they can leverage to solve it. They also are detail oriented. They know that without attention to detail, they would have to rely solely on hope that strategies are being operationalized.

-

Exhibit energy and drive. High-performing executives are self-motivated and driven. Because they have more fire inside, they need less fire underneath to drive them forward.

-

Collaborate freely. Because these executives primarily are motivated by achievement as opposed to power, high-performance cultures are highly collaborative. Leaders and managers have the personal humility to seek answers and assistance from colleagues at any level of the organization, and that help is given willingly and accepted gratefully.

Combined with a strong performance ethic and a passion for renewal, this approach to leadership produces not just better results but best-in-class outcomes. Companies that historically perform well and then fall from grace often do so because they lack critical ingredients of high performance or let important elements erode. Success breeds complacency, feelings of invulnerability and lack of humility. Status seeking, risk aversion and bureaucracy overtake collaboration, innovation and self-direction. Comfort, not aspiration, rules. When things go wrong, blame is plentiful and solutions are scarce. Decline is imminent, and reversing the tide is a herculean task. As the stories of such companies suggest, corporate culture, in many cases, hasn’t been consciously chosen — it simply has grown up over time and can develop into any one of many types of cultures (see sidebar “A Field Guide to Cultures”).

Choosing the Road to High Performance

Choosing to create a high-performance culture requires ambition, vision and courage, particularly for companies that are performing acceptably. Why fix something that doesn’t appear to be broken? That attitude may be an early warning sign of decline and an indication that it is time to choose the road to high performance. Cultures, however, do not collectively decide to change themselves. The first step on the road usually is taken by a visionary CEO who recognizes that the company could perform far better and that the chief obstacle to improvement is the culture itself.

Change does not come overnight. Outperformers have developed their performance excellence systematically and in a disciplined manner over extended periods of time. Few can do it without help. And few can achieve it without investing in the organization. A one-person “process excellence office” or “Lean office” does not suffice — nor can the choice of adopting a high-performance culture and the associated tools be left to the discretion of individual executives.

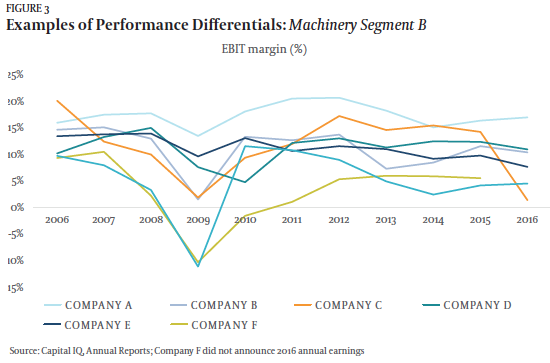

Though the culture-building process can take years, the rewards begin to manifest themselves from the outset. And they grow dramatically as the organization finds itself progressively better prepared to deal with changes in the competitive and economic environment. For example, note in Figure 3 how the top performer in an industrial sector not only consistently outpaced its rivals but also weathered the financial crisis far better than competitors did.

The journey to high performance can be exhilarating for those who are fit for it and clarifying for those who are not. But as the performance differential with rivals begins to widen, everyone in the organization should see that taking the road to high performance is not only a choice, it is an imperative.