The first edition of this report was published in the summer of 2022, and it laid out some disturbing data. Examining 21 of the largest Danish companies and the practices they deploy to attract, develop, retain, and promote female talent left a lot to be desired. Tracking the six managerial levels below the CEO, we observed a gradual decline from the sixth level, where women comprised 30%, to the first level, where it was 21%. The share of women CEOs was 8%, while the chair level, at 6%, exhibited the most significant gender gap in Danish leadership teams. These numbers clearly helped to illustrate the challenge before us as a society: we were not fully harnessing the potential of women, we were indisputably missing out on the effectiveness, innovation, and well-being that comes with diversity, and we clearly fell short of the level of fairness we often credit ourselves with in Denmark. In recent years, New Zealand and our four Nordic neighbors (Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) have consistently ranked in the top five positions on the World Economic Forum Gender Gap Index. With our current ranking at number 23, Denmark sticks out like a sore thumb.

On the qualitative side, we highlighted two major challenges: the ownership as well as the scope and persistence of the initiatives that companies deployed to ensure equity, inclusion, and increased gender diversity. We concluded the report with a commitment to revisiting the participating companies in 2023 with the hope of finding more:

- Leaders who take ownership of DEI

- Transparent ambitions and goals that are broadly communicated

- Systemic changes that embed DEI practices

- Role modeling that promotes behavioral change

- Focus on doing, not explaining

So, how are the companies doing on their respective journeys? The short answer is: better. While the numbers have improved only slightly, there are solid grounds for optimism when looking at the ownership of the DEI agenda and on the scope and persistence of activities. Clear responsibilities have been placed squarely throughout organizations, from the chair to the team leader. Also, the many infrequent one-off initiatives (e.g., ad hoc unconscious bias training) are finally losing ground to recurring practices that are being embedded into the corporate fabric. We have seen the share of leaders who lead forcefully on DEI increase dramatically. We have seen widespread use of clear goals. We have seen that DEI practices are being institutionalized across almost all companies. And we have seen many examples of positive role models. All in all, we can track a clear progression from mere awareness of the problem toward acceptance and a fostering of activation to address it.

While there has been significant progress on ways-of-working since the first report, it bears mentioning that many companies have experienced increased opposition to DEI in the same period. The wider DEI concept, which includes religious belief, sexual orientation, mental and physical ability, etc., has become increasingly politicized, resulting in a noticeable opposition to ‘wokeism’ in certain cultures. In this context, gender representation is not as contested as other DEI dimensions. We double down on gender because this is where Danish companies and the society in which they operate face one of their most visible challenges, and because we firmly believe that if you cannot bring women into your management structure, you will have an even harder time including e.g., LGBTQ+ and ethnically diverse talent. If, on the other hand, a company succeeds in tackling the gender challenge by creating a more inclusive workplace, we firmly believe that there will be a spill-over effect, and new learnings, tools, and capabilities will increase the likelihood of succeeding with other minority groups. All the more reason to press on.

THE DATA

This report, the second in a planned series of three, builds on data from and interviews with 21 of the largest and most well-known Danish companies. We are grateful to all the participants from the first round who signed up to appear in the second round. Two companies dropped out due to transitions on key positions and were replaced with two newcomers, who had been unable to join the first installment. This consistency is in itself a testament to the heightened attention Danish companies are paying to the topic of gender balance on the managerial levels. Besides data and information from the participating companies, the report also builds on publicly available data and the latest research from academia and NGOs as well as Bain and Egon Zehnder reports and articles such as “The Business of Belonging: Why Making Everyone Feel Included Is Smart Strategy” (Bain, 2023), “Search 2.0: The Future of Leadership Appointments” (Egon Zehnder, 2023), “How Investing in DEI Helps Companies Become More Adaptable” (Bain, 2023), and “Bringing Action to Numbers: Turning Diverse Boards Into Inclusive Ones” (Egon Zehnder, 2023).

Most interested parties will be aware of the massive amounts of research documenting the substantial value and tangible benefits of diverse organizations and management teams. Diverse boards deliver higher growth and return-on-equity (ROE); diverse company management is more effective; diverse teams are more productive and innovative; academic papers written by diverse research teams get more citations; diverse organizations are more magnetic in terms of talent attraction and retention; employees in diverse organizations are significantly more likely to promote their workplace: the list goes on. But despite the abundance of evidence – and the clear moral imperative – the gender diversity challenge remains. Women in Denmark are clearly at a disadvantage not only vis-à-vis men, but also vis-à-vis women in our neighboring countries. This has a myriad of unfortunate moral, cultural, and practical implications. One such is that Danish companies are less diverse and thus less effective and innovative than they could and ought to be.

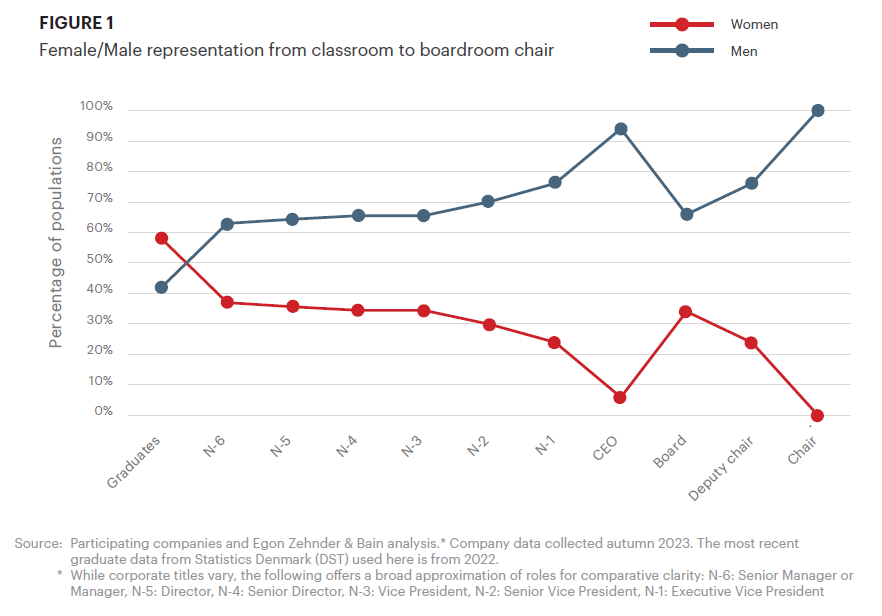

When taking a supply side view of this challenge, we can start with the fact that more women than men graduate from Danish universities (see Figure 1). While it can be argued that these numbers are only rough indications of the amount of female talent available to Danish businesses, they still provide a stark and alarming contrast to the rest of the data in Figure 1.

After leaving the classroom, Danish women will on average find themselves in the minority all the way to the boardroom, no matter which step of the career ladder they find themselves on. The share of women on the six management levels below CEO follows a downward trend, with the steepest declines emerging after the halfway point. This leaves us with two conclusions: 1) the participating companies do not develop female talent to the same extent as male talent and 2) this is aggravated at the final stages culminating at the CEO level. Boards tell a similar story, except that while there is only one female CEO out of 21, there are still no female chairs.

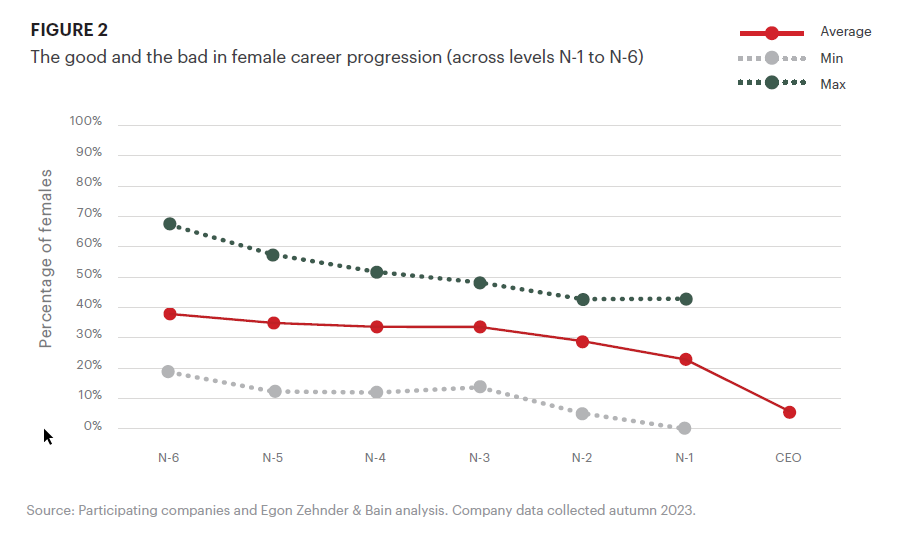

Figure 2 shows that some companies have reached 50% female representation or above at the lower managerial levels. Five companies were above this threshold, whereas no company exceeded 50% last year. While it must be acknowledged that two of those five companies did not participate last year, this is still a positive development. However, the data also shows that no companies are reaching parity at the higher levels, which suggests continued difficulty in retaining and developing female talent.

While the average closely mirrors last year’s trend, we unfortunately see negative movement as well. Keeping in mind that a direct comparison is not possible, the numbers on select levels show significant drops of up to 10 percentage points in the worst cases. This suggests that some companies are still facing significant struggles. A final piece of evidence of this challenge is that we still see Danish companies with no women on the group management level.

THE EVER-EVOLVING JOURNEY

While data are hugely important, a topic as complex as this obviously benefits from nuance. It is telling that our pessimism slowly evolved into cautious optimism only when we started to look beyond the data. We truly believe that effective leadership in diverse and inclusive environments builds on the ability to identify these nuances, engage them, and leverage them to find the path forward. At the onset of Female Force in 2022, we articulated the process of achieving DEI outcomes as a three-step journey:

It is a testament to the progress made in each company that this journey has become nearly obsolete. All participating companies have moved beyond mere awareness of the challenge to acceptance and activation. In other words, senior leaders no longer discuss the what and the why but rather the how. Some are only just coming to grips with the significant task ahead, while others are already firmly engaged with activation. In fact, the most progressive companies, who are far into activation, are now starting to discuss how to safeguard against complacency. One of the ways to avoid going on ‘auto-pilot’ mode and ensuring a sustained focus is by making it evident that activation is a means to an end, not an end in itself. This can be visualized by a new roadmap that includes the end state. A humble suggestion is the following open-ended three-step journey:

Assiduousness is the stage where gender equity has become the natural status quo – both culturally and structurally. It is the stage where the focus has moved to creating equity for other groups utilizing the learnings and competencies gained during the journey toward gender equity.

THE DIVERSITY LEVERS

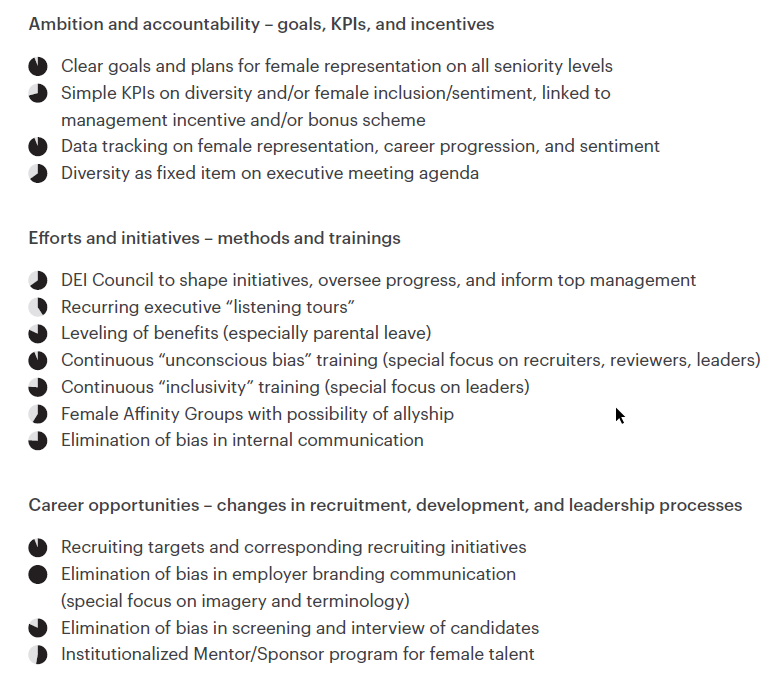

The diagram below outlines 15 diversity levers, which were also laid out in last year’s report. When coupled with the data in Figure 1 (see above), these levers help to give a fuller picture of the initiatives underway at Danish companies. The diagram includes some of the most prevalent initiatives, tools, and methods widely used in countries that rank above Denmark on the WEF Gender Gap Index.

When looking at ambitions and accountability, the clarity of goals and plans for female representation on all seniority levels is increasing (now at 94%, up from roughly 75% last year). The granularity of these targets does, however, vary greatly – from an all-encompassing company-wide intent over specific goals for each seniority level and down to targets for individual teams. It must also be said that the action plans behind the quantitative ambitions are in some instances still largely works-in-progress.

Companies are still grappling with whether they should tie C-suite bonuses to DEI targets. Seventy-one percent of the participants have deployed this measure, while the rest remain hesitant, arguing that they prefer that decision-makers act for ‘the right reasons’ and not for transactional value. Most of the companies (94%) track data on female representation and sentiment, although the level of granularity varies greatly among them. Sixty-five percent of companies have diversity as a frequently and systematically recurring item on the top management agenda, a significant jump from last year’s roughly 10%. However, this notable shift also reflects the substitution of two companies mentioned in the data chapter above.

Accounting for each of the many efforts and initiatives that are in play to increase gender diversity in large Danish companies is not easy. While DEI councils (i.e., a forum comprising global and local DEI owners and leaders) are almost universally used abroad, 65% of participating companies now report having established them. This marks a significant increase from around 20% last year. Such councils typically convene on a quarterly basis and are tasked with driving material progress on DEI ambitions, monitoring progress on all initiatives and targets, issuing calls-to-action when local improvements are not sufficient, and organizing various events with speakers, debates etc., (e.g., on International Women’s Day, Pride Week, etc.). Forty-one percent, up from roughly 10% last year, utilize yearly listening tours, which entails that the CEO and/or top management team tours various parts of their respective companies to listen and talk to employees on topics related to diversity, inclusion, and culture in general. Besides role modeling and making employees feel heard and seen, this also gives leaders a first-hand impression of the company culture and the many shapes and forms it takes in different geographies and functions.

A majority of the companies (82%) are actively working to level parental leave policies. However, many pointed out that Danish culture is still permeated by the assumption that women are more unreliable and consequently less financially valuable employees; a perception that arises from the expectation that women are more likely to be more absent from work than men when they have children. People naturally align their career decisions with caregiving responsibilities and how they share these duties with a partner. It is crucial that men and women in Denmark face the same challenge of balancing work and caregiving.

Turning to training, 94% of the companies have implemented either obligatory or voluntary unconscious bias training. This is obviously important for all employees, but especially critical for people with recruitment, assessment, and leadership responsibilities. It is a well-established fact that all people harbor unconscious biases, and that it is inherently productive for us to be made aware of these at regular intervals. Most companies are in the process of institutionalizing the training, i.e., moving away from ad hoc event-like initiatives. This is a clear sign of progress. It is no secret that low-priority initiatives are set up to fail. A majority of the companies (roughly 76%) demonstrate an unwavering commitment to long-term change through dedicated inclusivity training.

Fifty-nine percent of the participating companies have established formal women’s affinity groups, while considerably fewer have created an option for men to support these groups through allyship. An affinity group is a group of people with common interests, background and/or experience that come together to support each other, coordinate viewpoints, and speak with one voice. Such groups will often meet bi-monthly and typically invite all colleagues to relevant events, where important events (e.g., International Women’s Day, Ramadan, Diwali, Pride, etc.) are celebrated, new research is presented, and internal/external speakers enlighten an audience. This helps ensure and facilitate a broad understanding and acceptance of minorities and their views, competencies, and needs.

The purpose of affinity groups is not to foster echo chambers or isolate individuals within or outside the group. Instead, the aim is to transform the broader corporate community into a cultural learning community where minority groups can unite, engage with, educate their colleagues, and thrive. However, a handful of companies expressed resistance to this lever during the interviews. Various reasons were provided, the most common being that affinity groups exclude more than they include, sparking the age-old debate about equality vs. equity.

All participating companies acknowledge the importance of unbiased communication. The vast majority have made adjustments to their internal and external communication. Job postings, newsletters, white papers, etc., are more thought through than earlier, though most feel that there is still room for improvement. Companies are diligently working to eliminate gendered language, replacing terms like ‘mankind’ with ‘humankind,’ ‘maternal/paternal’ with ‘parental leave,’ and ‘wife and husband’ with ‘partner’ or ‘spouse.’ Perhaps most tellingly considering the name of this project, some also substitute the use of ‘female’ with ‘woman/women.’ These efforts obviously also entail getting rid of the ever-present sports and war metaphors.

The interviews revealed that an overwhelming majority pays special attention to career opportunities for women, spanning across recruitment, development, and leadership processes. Almost all the companies (94%) have gender-based recruiting ambitions and activities in place. All the participating companies have made changes to their external employer branding communication and a few even use advanced software to eradicate counter-productive language and images from their external communication. Many companies (82%) are working to eradicate gender bias from these processes by deploying automatic screening, unconscious bias training of recruiters, blinding of CVs before interviews (to avoid pre-interview bias), etc. At many companies (76% and counting), significant changes have also been made to internal communications.

As Figure 1 clearly shows, improving development and retention of women at critical attrition points is key to strengthening representation at the upper levels of management in large Danish companies. And many of the measures discussed in this report will help companies accomplish that. A final measure, which is in use at half of the participating companies and enjoys widespread use abroad, is sponsorship programs. Here, the direct report structure is augmented (for female talent) with a ’sponsor,’ typically from senior leadership. Obviously, a lot of informal sponsoring goes on in all companies. The reasoning behind establishing a formal program aimed at women is that leaders can only sponsor a limited number of talents. People are biologically inclined to sponsor people who resemble them with regards to nationality, language, education, interests, and gender. If the leadership reflects the diversity they aim to support, organic sponsorship is effective, eliminating the need for a formal program. Yet, given the stark gender disparity in top positions within Danish companies, a formal sponsorship program focused on women becomes a logical tool to turn to. A sponsorship program will typically cover career planning, opportunity identification, enhancing internal and external network, and striking a sound balance between work and private life. As with other affinity groups, some companies argue that women should not get special treatment, which, again, is not the aim or indeed the case.

The many positive findings in this report are not only owed to the CHROs, the People and Organization teams, and the DEI advocates on the frontlines of this challenge. They are also owed to several CEOs who have taken clearer ownership of this agenda. In the first report, we identified ‘ownership’ as the main challenge, especially among chairs, boards, CEOs, and executive teams. While we do not harbor illusions about changing such a deeply ingrained phenomenon, we do tip our hats to the cultural somersault that many companies have successfully executed. The next section is dedicated to sharing some of the ideas we picked up during the interviews. These ideas are the work of people who have taken clear ownership of the agenda at their respective companies, and we are excited to see how many of these ideas will be added to our list of levers going forward.

IDEAS

During the interviews we encountered an appetite for change and heard numerous inspiring and successful ideas. The creativity and dedication we saw was enough to convince us that proactive change is well underway at a vast majority of the participating companies. Some of the most innovative ideas we heard during the interviews were:

TOWARD 2025

This report has found no significant shift in the representation of women in leadership roles within major Danish companies. And that is no surprise. Such changes develop over time, and transforming the foundation for female leadership in Denmark is going to take years. Despite not finding major improvements in the actual numbers, the report did, however, identify significant improvements in the conditions necessary for change. The participating companies have institutionalized changes, practices, methods, and metrics that will ensure quantifiable results in the coming years. As such, this year’s report will hopefully leave its readers on a more positive note than its predecessor.

As already mentioned, optimism must not grow into complacency where hard-earned gains vaporize as focus diverts from DEI, or as more short-term priorities come to overshadow it. A wide range of actions and developments – from individual leadership behavior to EU legislation – can help companies and leaders keep the DEI agenda front and center. The following is a non-exhaustive list of examples:

BIASES vs. VIRTUES

We do not see people as they are but as we are. This simple statement has been used to put the spotlight on biases. However, it can also put the spotlight on virtues. When do we pivot from eliminating biases to developing and enhancing virtues? When do we become more proactive and articulate our position, even when it is not called for or on the agenda? What does it take for individuals to step up and lead on DEI agendas even if it is not part of their job description?

PEOPLE vs. SYSTEMS

The gender part of DEI has been summed up in the maxim: Do not fix the women, and do not blame the men. A clear conclusion of this report is that gender balance in the upper levels of Danish companies is not about fixing women (i.e., encouraging them to behave more like men) or blaming men; it is about changing our methods, practices, metrics, and communication to ensure equity, inclusion, and, eventually, diversity.

MORALITY vs. LEGALITY

According to recent data from the World Economic Forum, the global gender gap could take 131 years to close after an entire generation of progress was lost due to Covid. This serves as a harsh reminder of the uneven distribution of caregiving responsibilities at home and a brutal reminder of how fragile progress can be when faced with geopolitical, economic, and healthcare headwinds. Legislative measures are needed to help safeguard gains and accelerate progress. The 2020-2025 EU Gender Equality Strategy, with directives on e.g., pay transparency and women’s representation on corporate boards, is an example of meaningful intervention that holds the potential to instigate broader cultural shifts by establishing a legal framework for change and suggesting a moral benchmark for our society.

To ensure continuity and hopefully allow us to track even more progress, the commitment from Bain and Egon Zehnder is to continue the Female Force project with a third and final round of interviews in the coming year. We dare to hope that, by then, diversity will no longer be referred to as an instrument or a program but simply a flow; inclusivity will no longer be a challenge but simply a reflex; and we no longer talk about female and male leaders but simply about good and less good leaders.