The World Economic Forum’s 2021 edition of the Global Gender Gap Report presented several worrying findings. The report benchmarks 156 countries on the evolution of gender-based gaps using four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity, Political Empowerment, Education and Health) and tracks progress toward closing these gaps over time. One of the disturbing findings in the 2021 report is that the projected number of years it will take to close the global gender gap has increased by a generation – from 99.5 years to 135.6 years, an increase largely driven by the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. The pace at which the pre-pandemic gap was closing was already disheartening, but the fact that it is now going the wrong way makes the continued struggle all the more important.

When looking at Denmark there are also grave reasons for concern. The countries at the very top of the 2021 Gender Gap Report are Iceland (#1), Finland (#2), Norway (#3) and Sweden (#5). New Zealand (#4) is the only non-Nordic representative in the top 5. Conspicuous by its absence, Denmark, a country that also used to rank at the top, has now dropped to #29 on the list. To paraphrase Shakespeare: Something is indeed rotten in the state of Denmark.

The Data

This report builds on data from and interviews with 21 of the largest and most well-known Danish companies – but it also builds on publicly available data and the latest research from Egon Zehnder and Bain & Company. The illustration below is based on consolidated data from the participating companies, and as such it does not present an 100% accurate illustration of female representation in Danish businesses. It does, however, reflect the challenge before us as a society: We are underutilizing our female talent, we are less diverse and thus less effective and innovative than we could be, and perhaps also less fair than we should like to think.

This well-documented challenge is somewhat of a conundrum as we have equally well-documented cascades of research available that shows the significant value and tangible benefits of diverse societies, organizations and management teams. Diverse boards are proven to deliver higher growth and return-on-equity (ROE); diverse management teams are proven to be more effective; diverse teams are proven to be more productive and innovative; academic papers written by diverse teams are proven to get more citations; diverse organizations are proven to be more magnetic in terms of talent attraction and retention; employees in diverse organizations are significantly more likely to promote their workplace, etc. The quest for gender diversity is clearly not a zero-sum game. It is rather a win-win-win-win for our societies, companies, families and for all the women, men and children who make up these entities. But despite the abundance of irrefutable evidence – and the clear moral imperative – the gender diversity challenge remains.

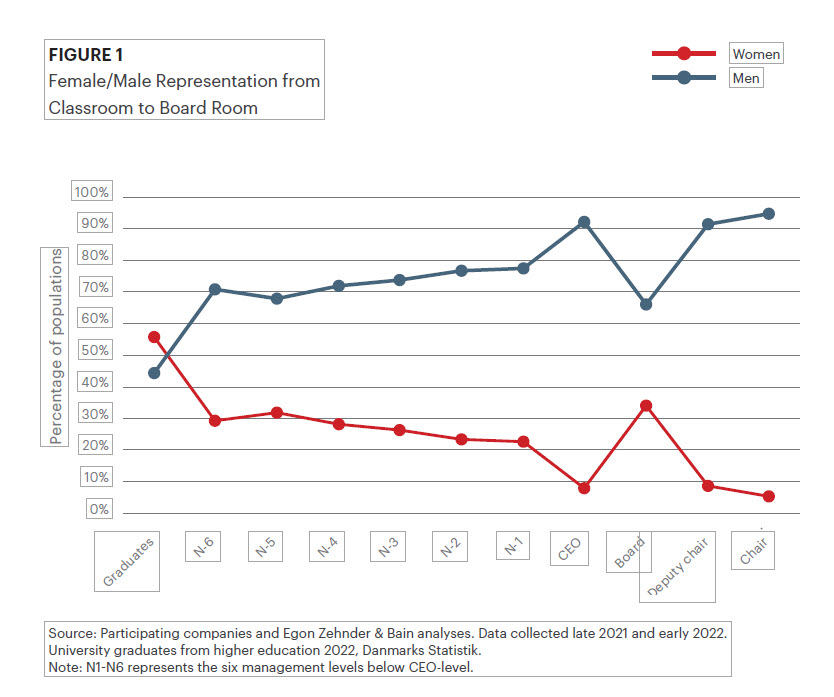

Figure 1 shows that more women than men graduate from Danish universities (55.8%). It can, of course, be argued that this Figure is not an entirely precise proxy for the pipeline of female talent available to Danish companies. However, whether the correct number is closer to 50%, or indeed 45%, the indisputable reality is that women are in the minority when it comes to leadership positions, no matter what stage of the career ladder the women find themselves on.

Although female representation recovers somewhat at board level (to a somewhat unimposing 35%), this might very well reflect that board composition is the easiest lever for companies that want to pull a quick fix. Certainly, the corresponding figures for female board chairs dip emphatically to well below 10%, where sadly, we also find the share of female CEOs. The share of women at each of the six management levels before CEO follows a clear downward trend – from the early stages of the career path, where female representation is in the high twenties, to the later stages with representation in the low twenties. This obviously indicates that the participating companies, on average, do not develop female talent to the same extent as male talent. When leaving the university class rooms, Danish women make up the majority, only to find themselves a clear minority when entering the corporate board rooms… That the journey to get there has been a more or less perpetual downward slide only adds insult to injury.

The Central Challenge

It is inherently positive that all the invited companies (with one exception) immediately decided to contribute to this project. These decisions were made by the respective CEOs and CHROs of each company, which shows that gender diversity is seen as a challenge that companies need to address. What is less positive is that the ensuing interviews were con-ducted with the CHRO and/or Head of DEI of each company, with the CEO present in only two instances. Incidentally, both these CEOs were women. Clearly, gender diversity is considered important, but not important enough to warrant CEO ownership. Gender Diversity is, to a large degree, still seen as an HR issue – and in quite a few cases it is compartmentalized even further as a DEI issue. This became clear not only because of who participated in the interviews, but even more so because of what came out of the interviews. More than 95% of the participating companies recognize that the gender diversity agenda and responsibility must be owned by top management. However, an equally impressive number, including both Bain and Egon Zehnder, have ended up placing it firmly in the hands of the HR-team.

When all the interviews were conducted and all was said and done, this point about ownership emerged as the central challenge.

It became very clear that without full commitment and continuous attention from top management the strength is simply zapped out of the many different gender diversity efforts that Danish companies have undertaken. It is important to stress that this conclusion has been reached after interviewing companies that recognize DEI as an important issue. It is difficult to imagine how the central challenge would have been phrased if the interviews had been conducted with less progressive companies. Nevertheless, it is only when the question of female representation across seniority levels is owned at the very top that actions to improve gender diversity will achieve full organizational impact, produce real results and thus become less theoretical. The gender diversity challenge cannot be fixed by deploying select DEI initiatives or even entire programs. It runs broader and deeper than that. If Denmark is to rise to the level of the other Nordic countries at the top of the WEF Gender Gap Index, we not only need the full force of our HR and DEI organizations, we also need those at the very top to take owner-ship. Like all cultural changes, gender diversity change must be initiated, addressed and led from the top, by chairs and CEOs.

When top management is focused on and engaged in ensuring gender diversity, other less pervasive challenges, such as the ones described in the following section, will be easier to tackle and overcome.

The What-Now

The question of Gender Diversity must be owned by top management, i.e., Chair and CEO.

The Diversity Levers

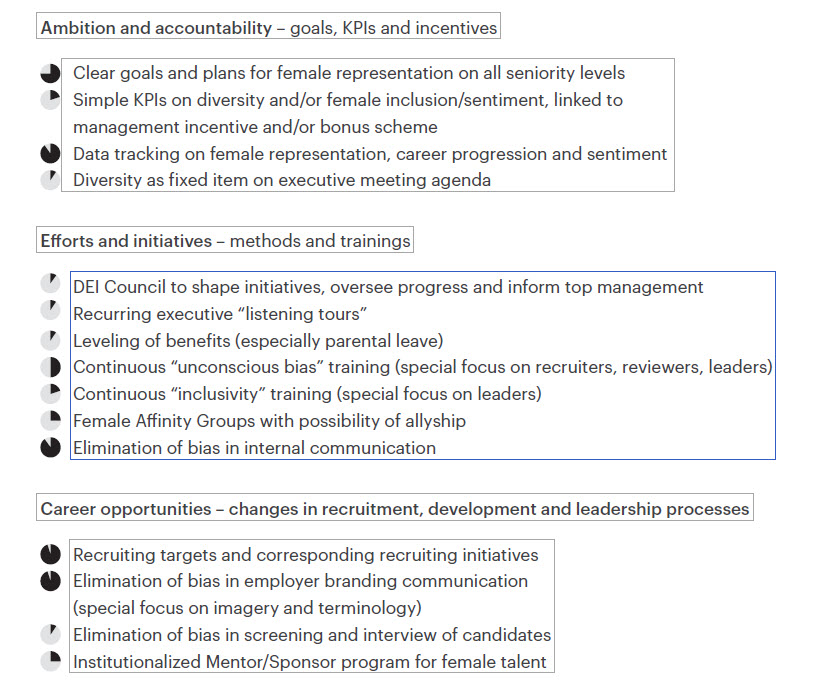

The interviews with the participating companies made it clear that they were all committed to gender diversity and wanted to act. However, less than 10% of the participants could demonstrate a comprehensive and institutionalized set of measures to ensure that they deliver systematically on this intent. On the other hand, the companies that struggled to demonstrate any efforts above shallow internal calls to action made up less than 10%. The middle group has implemented and/or experimented with varying degrees of one or more of the following initiatives, which largely makes up the programs put in place by the best performers:

The consolidated picture when looking at ambitions and accountability made two things stand out: ambitions are generally (somewhat) clear, while accountability generally remains (somewhat) blurry. Two thirds of the participating companies have some sort of target and/or goals related to gender balance in place. The granularity of these targets varies greatly – from an all-encompassing company-wide intent to specific goals for each seniority level. However, when scrutinizing the action plans behind the quantitative ambitions, these were generally unconvincing and in more than one third of the cases based solely on one-off initiatives as opposed to institutionalized or recurring practices.

When looking for the use of diversity or inclusion KPIs for leaders, this turned out to be even less prolific among the participating companies. For example, less than 25% measure how inclusive their leaders are. Among those that do, less than a handful has linked these measures to incentives such as promotions or bonuses. A majority of the companies track data on female representation and sentiment, although the level of granularity varies greatly among them. What is even worse is that the systematic follow-up on findings also varies greatly, which in turn questions why these measurements are made at all. A kind assessment reveals that no more than two companies have diversity as a frequently and systematically recurring item on the top management agenda.

The What-Now

There must be clear multi-level targets for Gender Diversity with corresponding actions that are institutionalized (e.g., unconscious bias training of leaders cannot be seen as a one-off activity, but should be a recurring, natural part of the leadership training curriculum). Individual diversity/inclusion/sentiment related KPIs for leaders and real consequences of non-performance must be in place. Relevant diversity data incl. percentages, progression and sentiment must be tracked. A systematic follow-up on data must be established. And, finally, top management must show systematic and frequent attention to DEI status and progress.

Accounting for each of the many efforts and initiatives that are in play to increase gender diversity in large Danish companies is not easy. We have singled out some of the most prevalent examples, including a few that are commonly used in countries placed above Denmark on the WEF Gender Gap Index. Also, we have given special focus to recruitment, development and leadership processes, which is the topic of the subsequent section.

While widely utilized abroad, less than 10% of the participating companies reported that they had established DEI councils, which is a forum consisting of global and local DEI owners and leaders. The council typically convenes 3-4 times a year and is tasked with driving material progress on DEI ambitions, monitoring progress on all initiatives and targets, issuing call-to-action when local improvements are not sufficient and organizing various events with speakers, debates (e.g., on International Women’s Day, during Pride, etc.). Equally few of the companies utilize yearly listening tours, which entails that the CEO and/or top management team tours their respective company to listen and talk to employees on topics related to diversity, inclusion and culture in general. Besides role-modeling a conducive leadership behavior and making employees feel heard and seen, this also allows the person taking the tour to get a first-hand impression of the company culture and its subcultures. One company representative raised the important point that listening tours that do not provide feedback to the organization and lead to subsequent actions can be counterproductive.

A vast majority of the companies struggled with the role of benefits, not least their parental leave policies. A great many pointed out that Danish culture is still permeated by the assumption that women are intrinsically more unreliable and consequently less financially valuable employees, because women most likely will be more absent than their spouses when they have children. Motherhood is quite simply a kiss-of-death to a career. Despite this obvious discrimination of women, only a small minority of companies have followed through by e.g., leveling benefits to ensure that men and women are equally incentivized to enjoy time with their infants.

Turning to training, roughly 50% of the companies have implemented either obligatory or voluntary unconscious bias training. Half of these have not institutionalized the training but rather regarded it as one-off events or have given up on it due to a perceived lack of results. In the latter case, the unconvincing approach was often indicative of an immediate need to ‘check the DEI boxes’ as opposed to an unwavering commitment to long term change. It is no secret that low-priority initiatives are set up to fail, and this is also the case with random DEI initiatives. Research shows that all people harbor unconscious biases, and it is inherently productive for us to be made aware of these with regular intervals. Needless to say, this is especially critical for people with recruitment, assessment and leadership responsibilities. Around 20% of the interviewed companies had experiences with inclusivity training, but aside from the difference in adoption, the fate of this specific training more or less matches the fate of unconscious bias training. Research shows that unless people are actively inclusive, they will most likely be perceived as the opposite. The consequence, especially for leaders, will be all kinds of counterproductive effects (demotivation, attrition, reputational damage, etc.).

Surprisingly, less than 25% of the participating companies have established formal women’s Affinity Groups, and less than 10% have created a possibility for men to support these groups via an allyship option. Such phenomena are the norm in other countries, not least the US where minority groups (e.g., various ethnic and religious groups, veterans, people with disabilities, etc.) will be members of an affinity group established to ensure that all employees feel that their voices can and will be heard. Such groups will often meet 4-5 times a year and typically invite all their colleagues for regular events to present and discuss new research, new data and/or listen to internal/external speakers. This helps ensure and facilitate a broad understanding and acceptance of minorities and their views, competencies and needs. On that note, almost all the participating companies are aware of the importance of communication. A vast majority mentions that they have changed several features of their internal communication. Greetings, metaphors, images are more thought-through than earlier, although the majority feel that there is still room for improvement. Mass-greetings like “Gents” and “Guys” are not popular when there are women in the room or on the email. Nor does football-banter or Formula One-metaphors seem to have won many female hearts. The same goes for the ever-present war-terminology (must-win battles, take flak, go to the trenches, firepower, etc.).

The What-Now:

A formal DEI Council that reports to Chair or CEO must be established. CEO and possibly the entire top management team must embark on yearly listening tours. Benefit packages must be conducive to gender equity. Unconscious bias and inclusivity training must appear on the training curriculum. Formal women’s Affinity Group(s) must be in place. Internal communication must signal active and broad inclusivity.

The interviews revealed that an overwhelming majority had paid special attention to female career opportunities spanning across recruitment, development and leadership processes. Almost all the companies have gender-based recruiting ambitions and activities. Nearly all the participating companies have made changes to their external employer branding communication and a few even had advanced software to eradicate counter-productive language and images from their external communication. These changes are much in line with the changes made to internal communications, but many people feel that there is still more to do. Also, when it comes to policies that ensure focus on gender equity in the screening and recruiting practices, almost all companies are onboard, while only a minority are tracking/documenting the actual changes in outcome. For example, many companies mentioned principles such as “no final list of candidates without female representation,” which is positive, unless, as one participant pointed out, it is a check-box rule with little real effect, in which case it essentially signals a cynical lack of respect. A minority of the companies in question are working to effectively eradicate gender bias from these processes by deploying automatic screening, unconscious bias training of recruiters, blinding of CVs before interviews (to avoid pre-inter-view bias), etc.

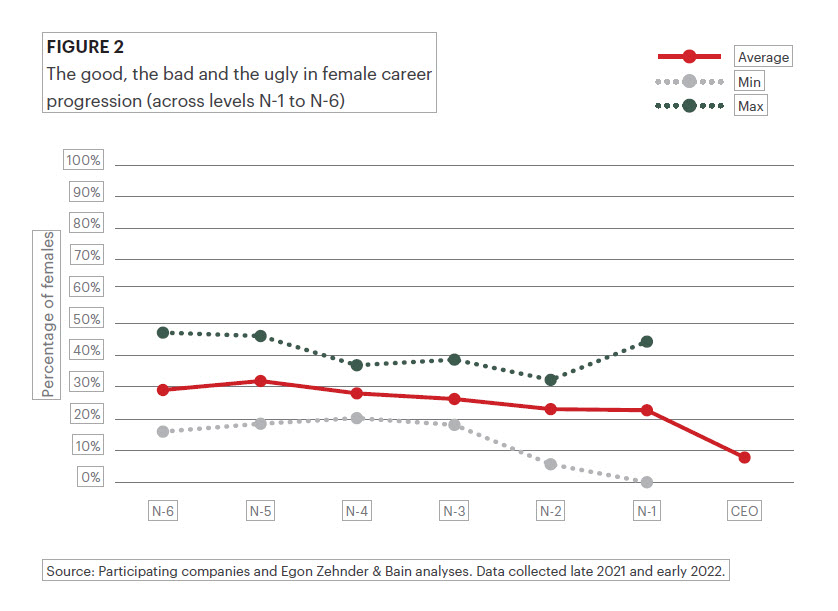

When looking at the phases following recruitment, data from the participating companies (see Figure 2) speaks volumes. On none of the six management levels below CEO does the best performing company, of all the participants, reach 50% female representation – the best company, on each level, reaches between 47% and 33% with a clear downward trend. The recovery at EVP (N-1) level can most likely be explained by the limited number of people at this stage, making it easier to change, or “manipulate,” for the better.

Assuming, however, that Danish companies aim to close the gender gap, this curve showing maximum scores certainly seem to highlight the magnitude of the challenge.

The best performing, among the largest and most well-known companies, seem unable to clear the 50% threshold and close the gap. As for the worst performers, let it suffice to say that we still, in 2022, have major companies with 100% male top management teams (N-1). Improving development and retention of women at critical attrition points is obviously key to improving representation at the upper echelons of management in large Danish companies. And many of the measures discussed in this report will help companies accomplish that. A final measure, also worth mentioning, which is in use at a quarter of the participating companies and also enjoys widespread use abroad, is female sponsorship programs. Here, the direct report structure is augmented (for female talent) with a “sponsor,” typically from senior leadership. Sponsorship of all kinds of talent happens naturally in most organizations, but this is a formal program to ensure sponsorship of female talent. A sponsor must believe in the receiver of the sponsorship and be ready to use her/his own influence and reputation on the receiver’s behalf. Areas covered by a sponsorship program will typically include career planning, opportunity identification, enhancing internal and external network and striking work/life balance. While these programs are seen as being very effective by companies that use them, others argue that women should not get special treatment (this in turn invokes the age-old discussion about equality vs. equity).

Quite a few of the participating companies mentioned self-invented but nevertheless successful levers, one such example is a diverse team target initiative, building on a rule of maximum 75% homogeneity (covering gender and ethnicity) for each and all teams. All such initiatives are positive, but if we are to close the individual and the consolidated Danish gender gap, we need to adhere to a classic song lyric: Everything counts, in large amounts.

The What-Now:

There must be clear DEI ambitions for recruitment. Employer Branding comms must be well thought through. The recruitment process – from screening to final evaluation – must be bias free. There must be clear ambitions for diversity at all management levels (and possibly in individual teams). Tracking of diversity data on all levels (possibly teams) must be in place. Talent development processes must cater to diversity. There must be a formal Sponsorship Program aimed at female talent in place.

Toward 2025

The global gender gap still looks like an insurmountable chasm posing moral, economic and creative challenges to societies, organizations, families and individuals. The world is less fair, productive and innovative than it could be. For no good reason. And at a time where we need to be more fair, productive and innovative. Denmark has a gap of its own to close, and Danish companies will need to do their part if Denmark is to attain a position among the other Nordic countries at the top of the Gender Gap Index over the coming years.

With research-based thought-pieces like e.g., “The Fabric of Belonging: How to Weave an Inclusive Culture” (Bain, 2022), “Reversing the She-cession” (Egon Zehnder, 2021), “Ten Proven Actions to Advance Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” (Bain, 2021) and “Combining a Bird’s-Eye View with a Laser Focus for Real DEI Impact” (Egon Zehnder, 2021), Bain and Egon Zehnder continuously contribute to the growing list of DEI-related publications from professional services firms, academia, institutions, organizations and experts. These materials present a range of themes, dilemmas, ideas, solutions and tools that should be recognizable to all decision-makers. Many of them are highlighted in this report.

In the spring of 2023, Bain and Egon Zehnder will re-invite the companies that were engaged and generous enough to participate this year to again share their data on female representation and to discuss the ideas, solutions and tools they are deploying to ensure DEI progress. It is our hope that female representation at Bain and Egon Zehnder as well as in all the participating companies have improved by then, but even more so that we will be able to see DEI practices at Danish companies characterized by:

- Leaders who lead on DEI. When chairs, boards, CEOs and top management teams are fully committed to DEI and communicate this continuously, the journey is well on its way.

- Clear and broadly communicated DEI ambitions and goals. A DEI ambition, reflected in specific goals for each area, level, leader and time period, backed up by tracking of progress and follow-up measures, remains instrumental for all change and thus DEI journeys.

- Promotion of individual growth to inspire broader change. As this report shows, all companies have “blind spots”, but they also all have unique “bright spots” and focusing on positive real-life stories of growth opportunities and career advancement for women can touch hearts, align stakeholders and build momentum for the journey ahead.

- Focus on needed behavioral and systemic changes. Research how women thrive in cultures where their colleagues are aware of their own biases and knows what active inclusion looks like and where they are able to connect with and rely on each other, DEI stakeholders, management, sponsors and other allies. However, their experiences are affected not just by their relationships with colleagues but with the company itself, which is why the role of incentive/bonus systems, formal councils and affinity groups, sponsor programs, etc., are also critical to the long-term success of the journey.

- Focus on doing, not explaining. People learn to change not through theoretical exercises but through real-life practice, problem solving and unsentimental coaching.

The commitment from Bain and Egon Zehnder is to continue the Female Force project with annual data collection and interviews until the spring of 2025. By 2025, we hope diversity no longer feels like a program, but simply a flow, that inclusivity is no longer a challenge, but simply a reflex and that we no longer talk about female leaders, but simply leaders.