Over the past 15 years, the role of chief financial officer has evolved considerably. While the CFO may still carry the original mandate of master technician and “accountant-in-chief ”—and must do so under heightened regulatory and investor scrutiny—that is only a fraction of what the role entails today. A successful CFO must also have the judgement and gravitas to be a reliable and dispassionate counselor to the CEO on a broad range of business issues. Increasingly, he or she must also be able to be a strategic business leader; many CFOs now have oversight of other functions, such as information technology and compliance, and are expected to take enterprise-wide leadership roles in initiatives like acquisition integration and business transformation.

If the role has expanded so markedly, the professional development leading up to it must change in a similar way. This article explores what the path to CFO now looks like at various points on the trajectory of a well-prepared finance executive in four geographic markets that draw from overlapping pools of candidates: the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. These findings are based on hundreds of collective conversations and CFO search engagements with boards, CEOs and chief human resource officers.

The early stage: Building a foundation

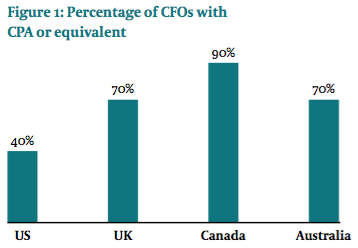

Generally speaking, future CFOs begin their careers either by pursuing accreditation as accountants or by assuming a series of operational finance roles (typically without going on to obtain a CPA or equivalent designation). The former have tended to dominate in Canada—and to a lesser extent in the United Kingdom and Australia—where there are stricter regulations governing public company accounting. The latter are more common in the United States, which places a greater emphasis on operational finance and business partnering skills (see Table 1). In the United States, there also is a notable minority of future CFO candidates whose first in-house position is in treasury. Often, these individuals, like their more numerous operational finance colleagues, are without a CPA.

Regardless of the track on which the future CFO begins, the early years will be spent gaining the corresponding technical expertise and practical experience. Those who have the fortune of beginning their careers at one of the “academy companies” for finance, such as PepsiCo, P&G, General Electric or Unilever, will have a particularly solid foundation from which to grow. But even those financial officers will need to broaden that base as they move into their mid-career phase.

Mid-career: Broadening the skill set

While the first decade on the job for the future CFO’s looks much as it always has, the second decade reflects how the role has expanded beyond technical skill. At this point, the rising financial executive’s career must be actively managed to provide broad exposure to the range of issues and experiences with which CFOs are expected to be familiar.

The first order of business is to fill in the gaps in one’s early training. Until recently, a company could choose a CFO based on its particular circumstances and mitigate whatever shortcomings there may be through well thought-out appointments on the CFO’s direct team (e.g., a “strategic” CFO could have a particularly strong treasurer and controller; a “technical” CFO would have a strong head of financial planning and analysis). In the current environment, however, such fixes are less satisfactory. In the United States, for example, a public company CFO is personally liable for the accuracy of company financial statements; in Canada, there is a growing appreciation of the importance of having a CFO who is also a strategic thinker. And in both markets, the ability to access capital markets and manage the capital stack is critical. The potential CFO needs to have a holistic view of his or her responsibilities and be without weak spots in critical domains.

Therefore, the finance executive with a controller background will need to spend time leading the FP&A function, forcing the executive to look beyond the numbers to the business implications. However, a strong technical accountant may well meet resistance when attempting to make this move because of how valuable his or her technical expertise is in an accounting role. It is therefore important to cultivate mentors and advocates, both within the finance and human resources functions, to help make such moves possible.

Those coming up the strategy or operational finance track need to strengthen their technical accounting knowledge. This is best done by holding a corporate-level position in the controller function. This role provides the critical experience of having final responsibility for the numbers. It is important, however, that this move be made relatively early in one’s career; as it is often difficult to take on this responsibility as a training billet at scale.

Finally, both “accounting” and “operations” finance executives need to spend time managing capital- and investor-intensive functions, such as treasury, capital markets, mergers and acquisitions and investor relations.

Experience across accounting, operations and capital markets covers the main pillars of the finance function. We note that tax experience is not often considered a “must have.” There are, however, three broader areas that demand attention:

Developing a broader sense of the business.

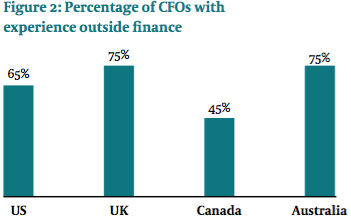

Just as it is critical to develop a holistic view of the finance function, the CFO’s role as a strategic business leader requires experience across the organization. For some time, it has been standard to include rotations to back-office functions like IT and procurement in financial officer development, but the prospective CFO candidate ideally should also push outside of this comfort zone to include operations and market-facing functions like sales and marketing. Figure 2 shows how experience outside of the finance function has become commonplace.

Strengthening leadership competencies.

Rotations into different aspects of the business provide exposure to various aspects of the enterprise. But it is also essential for the future CFO to be given responsibility facing different types of challenges. Overseeing a post-acquisition integration or taking charge of expansion into a new market requires leading cross-functional teams in uncertain environments and provides opportunities to test and hone core leadership competencies such as communication and influence, strategic orientation and performance orientation.

Gaining a global perspective.

By virtue of supply and customer chains, most organizations are global today. International postings—or global responsibility requiring frequent travel—provide important experience with the complexity of working in different jurisdictions and under different compliance and tax regimes. Increasingly, some type of foreign experience will be a “must have” requirement.

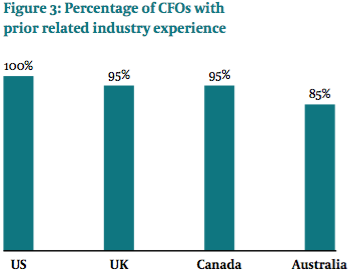

The mid-career financial executive should also give some thought to his or her industry experience. While the traditional view is that CFO candidates have high levels of mobility across industries, we also see contrary anecdotal evidence among the CFOs whose careers we examined (see Figure 3). Capital availability, financing structures, investor expectations and regulations have all become more specialized across industries, leading some boards and CEOs to prefer CFOs who hail from the same or a peripheral industry and thus have no additional learning curve to master.

Senior level: Preparing for the final step

If the aspiring CFO has been proactive in managing career development, he or she should have a solid track record and exposure to a wide variety of functions, environments and challenges. At this point, preparation for the CFO role is a matter of addressing any gaps that may remain. It is also important to have had—and continue to have—adequate opportunity to interact with the executive committee and board of directors on both financial and larger business matters. In some sense, the various points on one’s CV are table stakes; making the final step to the top of the function depends on having established oneself as a respected advisor and strategist who can act as an independent foil to the CEO and as a partner with the audit committee chair. A CFO candidate who has won the confidence of the board and executive committee is ready to become a face of the company to investors, regulators, analysts and other stakeholders.

Implications for organizations

For organizations, the more demanding and complex path to the CFO post requires the board and the chief human resources officer to place greater attention on CFO succession. With more CFOs rising to the role from within the same industry, especially in large and complex companies, additional effort is needed to develop and safeguard their pipeline of internal candidates. With forethought, however, organizations can build that pipeline with the combination of essential technical knowledge, leadership competencies and business judgement skills required for tomorrow’s chief financial officer.