For independent board chairmen of global companies, challenges continue to grow while room for error continues to shrink. Shareholders demand more rapid returns. Increasing regulation around the world demands exemplary corporate governance and rigorous compliance. Controversy about executive compensation has taken on new life in the context of rising income inequality. Meanwhile, the new breed of activist investors, with a small equity stake but big ambitions for shaking up companies and their boards, could come knocking at any moment.

To understand how today’s independent chairmen are meeting these and many other challenges, we interviewed chairmen and independent directors from several leading global companies where the chairman and CEO roles are split. As these in-depth conversations and our long experience of working with boards confirm, no one answer exists for any of these challenges.

The new breed of activist investors could come knocking at any moment.

However, the chances of arriving at the right answer in any given instance are greatly increased when the board’s leader focuses on improving the group’s effectiveness. That means adopting best practices in the board’s traditional “hard” responsibilities like risk oversight and succession planning, as well as attending to the “soft” side — the dynamics, culture and values, which are essential for harnessing the full potential of all members of the board. In these key areas of responsibility, independent chairs and directors recommended some specific actions that boards can take at a time when enhancing board effectiveness is more critical than ever.

Regularly Surface Risk

The independent chairs and directors we interviewed believe that the range of risks the board ultimately must oversee continues to expand. Financial, operational and reputational risks have been joined by cybersecurity and sustainability risks, which could pose existential threats. In addition, the rise of digital and social media poses strategic risks to companies that fail to pay attention to these powerful means of communication. Losing the war for talent presents another major risk in a world where people often are a company’s most powerful competitive advantage. Similarly, many directors see innovation — in products, services and business models — as an issue that cannot be neglected if the company is to avoid becoming a casualty of disruptive innovation.

Some of these risks may be poorly understood. “Many boards are not fully abreast of the advances in digital or cyber media,” says the chairman of a U.S. consumer durables company. “They must acquire expertise in areas like these or invite experts into the boardroom.”

With distance and time becoming less relevant due to the Internet and social media, companies and their boards must function in a world where instantaneous response is becoming the norm. “This puts huge pressure on boards,” says the chairman of a global oil exploration company, “as sometimes they have to address issues in China or Africa which they don’t fully understand or don’t have the time to understand.”

Most chairmen we spoke to agree that boards should have in place reliable mechanisms for surfacing and regularly discussing risk, as well as plans to manage and mitigate it. This means not just making sure risk is on the meeting agenda but also finding ways to elicit candid assessments from management, who may be reluctant to bring up issues which may reflect poorly on their performance.

“At each board meeting, I ask the CEO to articulate clearly the top three things that are going right and three that are not,” says the chair of an Asian multinational. “In one instance, innovation turned out to be an area which was not attracting the desired focus, and the CEO had been dismissive about it during past discussions around the failure of newly launched products.”

In the absence of mechanisms designed to ensure comprehensive and candid discussions of such issues, risks can become reality, turning risk management into crisis management. “I use management interaction to improve my understanding of what is going on in the bank,” says an experienced European chairman. “I do not rely only on the ‘tone from the top’ but also look for feedback and insights from the auditor, the risk officer and the CFO.”

Practice Rigorous Succession Planning

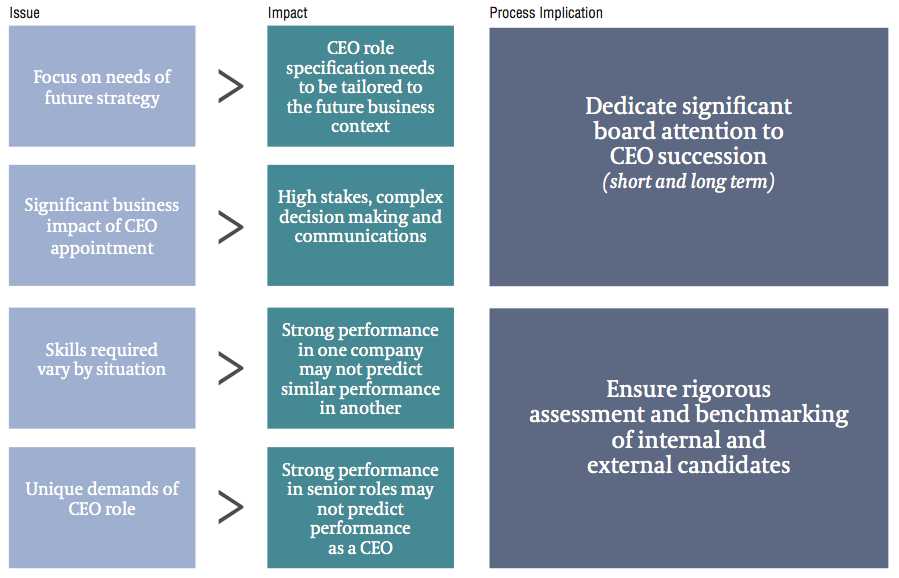

CEO succession planning remains a central responsibility for boards, and many directors see this as their most important duty. However, as some of our interviewees observed, it can present challenges (see Figure 1). “Planning orderly succession without attracting media attention is increasingly difficult,” says the chair of a global insurance company, “and it must be managed with great sensitivity.”

Succession planning is unequivocally the board’s responsibility and should be driven by the independent chairman, not the CEO.

Further, the board must address both long-term succession in preparation for a CEO’s planned retirement and emergency succession necessitated by an unplanned CEO departure. Boards often have a contingency plan for emergency succession, but because longer-term succession planning seems less urgent, they sometimes do not pay it sufficient attention. That is not the case at the global insurance company: “Succession planning is discussed at every other meeting of the board,” says the chair, “and information is shared transparently on the performance of possible successors.”

Succession planning is unequivocally the board’s responsibility and should be driven by the independent chairman, not the CEO. A comprehensive best-practices approach includes three essential steps:

- Develop the CEO specification: The specifications for the next CEO should be developed through interviews with key stakeholders, including all the members of the board, and a thorough understanding of the company’s likely strategy and business challenges at the projected time of the CEO transition.

- Assess internal candidates: With the board aligned around the desirable CEO profile, a succession committee and its advisors then can assess internal candidates against those specifications. Tailored development plans should be prepared for each contender to maximize his or her chance of becoming a serious candidate.

- Assess potential external candidates: The board and its advisors also should develop an external market map of leading potential CEO talent and evaluate it against the same CEO specifications used to assess internal talent. This benchmarking exercise enables the board to determine 1) if an ideal candidate even exists, 2) where internal candidates fall short and 3) whether an internal candidate is as good as, or superior to, the external talent.

Figure 1. Why Making a Good CEO Selection Is So Hard

Conscientious boards bring a similar rigor to board succession planning. “No independent directors can be appointed to our board unless they have been met by all our members,” says the chairman of a multinational pharmaceutical company. “Retirement and renewal dates are published well in advance, and nominations are discussed openly.”

What do the best boards look for in a potential colleague? An experienced independent director who has served on boards across three continents says, “We look for unquestioned honesty and integrity; a proven track record of creating value for shareholders; time available to undertake the responsibilities; an ability to apply strategic thought to matters at issue; a preparedness to question, challenge and critique; the determination to stay independent; and a willingness to understand and commit to the highest standards of governance.”

In summary, the chairmen and independent directors we spoke with want to make sure that when it comes to CEO and board succession planning, their most important decisions also are their best decisions. In both cases, this means not only being able to assess candidates’ experience (education, work history and accomplishments) and performance (demonstrated skills, abilities and results) but also their personality, style and potential. Candidates may have enviable experience and an admirable track record, but the ultimate question is how well they will perform in the future — as CEO or as a colleague on the board. Boards which practice real rigor in succession planning are able to answer that question and unlock great leadership.

Leverage the Full Benefits of Good Governance

A variety of forces is bringing uniformity to governance practices around the world: increased scrutiny by regulators, higher compliance requirements, the demands of institutional investors and the desire of companies everywhere to make themselves more attractive to investors. In our work with boards of leading global companies, we find a widespread and deep commitment to good corporate governance. Many boards embrace the challenges of good governance and seek to adhere to the highest standards, and the individual board members we spoke with are motivated by a desire to find the best way to fulfill their responsibilities.

The structure and functioning of board committees are critical for good governance.

Good governance, they agree, begins with a clear understanding that the board is there to oversee the company, not to run it. “The role of the board is not to drive performance or make operational decisions,” says one chairman, “but to hire the right CEO and then empower that person to deliver results.” By the same token, says the chairman, the CEO is expected to be forthright and open with the board: “The best way for the CEOto engage the board is by sharing relevant information well in advance. It would be unacceptable to be given information about a decision after it is too late to say no.”

Many of our interviewees also agree that the structure and functioning of board committees are critical for good governance. In fact, says the chair of a diversified multinational listed in several countries, “The quality of committee work is more meaningful than the full board meeting. Two-thirds of the total time should be spent in committees and one-third in meetings of the full board.” Adds another, “The chair’s role is to encourage the committees to have candid, substantive discussions and synthesize their conclusions for the full board.” With well-structured, high-functioning committees and a clear understanding of roles, the board then can set clear ground rules designed to bring transparency to matters which people generally do not find easy to talk about: CEO succession, independent director and chairman tenure, and board effectiveness.

Prepare to Engage in More Intense Strategy Discussions

Because everything emanates from corporate strategy, our interviewees broadly agree that involvement in strategy is a major responsibility for boards. Directors can add value by providing a dispassionate perspective and often long experience in a wide variety of situations. This contrasts with the executives who may be unable to see the discontinuities or inadequacies of a strategy because they are too close to the business. With a clear view of the company’s long-term strategy, the board also can determine how its composition should evolve in the coming years.

The chairman must guide the board through high-profile, often highly emotional conflicts.

Increasingly, however, strategy and board composition are being challenged in the short term by activist investors who take a small equity stake and then very publicly challenge management and the board. Often the activist proposes an alternative strategy — typically today, spin-offs or divestments of some of the company’s businesses. Activists also may demand changes in the board and offer candidates to replace directors the activists regard as being underperformers or lacking in relevant experience or knowledge. If the board refuses, the activist may initiate a bruising proxy fight. In these high-profile, often highly emotional conflicts, the independent chairman must guide the board to the response that ultimately is best for shareholders — whether that response means adopting some of the activist’s suggestions, compromising on changes to the board or opposing the activist at every turn.

The board’s role in strategy also has been magnified recently by the sharp increase in merger and acquisition activity. According to Thomson Reuters, 40,298 transactions — worth nearly $3.5 trillion — were announced worldwide in 2014, the biggest increase in deals since 2007. A major move, like acquiring a competitor or a complementary business — or deciding how to respond if the company has become an acquisition target — requires independent directors who have done their homework and a chairman who can orchestrate a thorough discussion of the implications of any of these possibilities.

Cultivate a Culture of Trust and Enable Productive Group Dynamics

Much of a board’s effectiveness results from its culture and dynamics. No one is better positioned than the independent chairman to set the tone for both. Ideally, our interviewees agree, the chairman will establish an atmosphere of trust and openness, elicit conversations that are candid and constructive, and encourage diversity of ideas combined with uniform dedication to the best interests of the company.

Interviewees were highly specific about ways chairs can promote a healthy atmosphere and productive interactions. Prior to meetings, the chairman should speak with independent directors and management to get a “feel” for what is on their mind and set the agenda accordingly. However, as one director points out, “It is troublesome when information is shared selectively with some board members by the chairman but reaches other directors through a third party.” During meetings, the chairman should have the wisdom and judgment to enable effective decision making without dominating a discussion or being the first to offer a view. “The chairman must be attuned to being fair, objective and balanced,” is a typical observation among interviewees. “The chairman is a facilitator among equals,” says a retired chair of a publicly listed global enterprise. “If the chairman dominates, then the agenda of the meeting gets hijacked.” When there is disagreement around the table and an issue must be resolved, the chairman should strive to create genuine alignment rather than force grudging consensus.

Ultimately, says an independent director, the chairman should create an environment which “encourages participation and allows board members to derive meaning, inspiration and satisfaction from their work.”

Conclusion: It’s about Maintaining Balance

Through these in-depth conversations with independent chairmen and directors, there ran a common thread: Ensuring board effectiveness is about balance. Effective oversight requires the ability to balance short-term returns with the long-term health of the company. Effective board composition entails the right balance of competencies, knowledge, diversity and experience in sync with the company’s strategy. For their part, independent chairmen must maintain balance in the way they conduct the board’s business: encouraging discussions which are candid but constructive and enabling openness but moving issues toward resolution.

Ensuring board effectiveness is about balance.

The splitting of the chairman and CEO roles is itself part of the quest for balance; in this case, it’s between oversight and operational responsibilities. The independent chairman’s work with the CEO, if it is to be productive, also requires a careful equilibrium. The relationship should be collegial, but it also should remain at arm’s length: independent but not oppositional.

Balance in all of these senses is not an achieved state but a process which requires conscious attention and considered action. As our conversations with these independent chairmen and directors confirm, thoughtful board members and chairmen work continually to maintain that balance.

Access the full paper How Chairmen Enhance Board Effectiveness.