Private equity investment in pipelines, storage terminals, and other energy transportation assets more than doubled from $4.3 billion in 2015 to $9.4 billion in 2017.1 This level of deal flow has unleashed intense competition for chief executive officers and chief financial officers to lead and transform these portfolio companies.

Private equity firms in midstream energy face two significant challenges in filling these key positions. The first is that ideal candidates are generally viewed to be executives who have held those roles at other companies and thus have a demonstrated track record of success at that level. However, the pipeline of former CEOs and CFOs will always be very narrow due to the simple structural fact that any energy company will generally have only one CEO and one CFO at a time, and successful teams often re-up as 'repeat teams' with their sponsor making them unavailable for new roles. This means that very often, private equity firms will be evaluating candidates for these roles who have not held them before—and thus increasing the risk involved in the appointment.

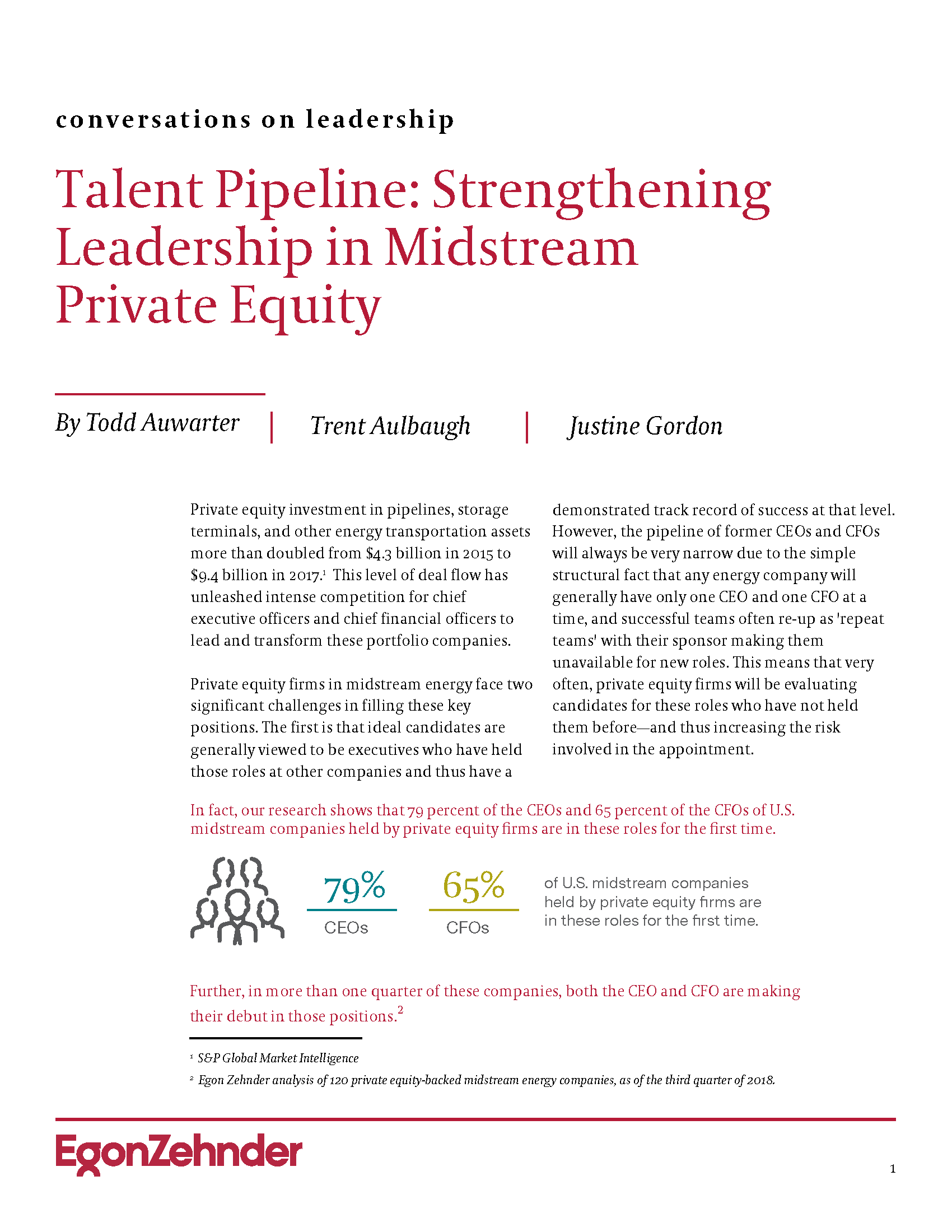

In fact, our research shows that 79 percent of the CEOs and 65 percent of the CFOs of U.S. midstream companies held by private equity firms are in these roles for the first time:

of U.S. midstream companies held by private equity firms are in these roles for the first time.

Further, in more than one-quarter of these companies, both the CEO and CFO are making their debut in these positions.2

Most private equity firms approach the evaluation of first-time CEO and CFO candidates by acknowledging the stakes and devoting more time and care to the due diligence and deliberation given to the candidate’s track record. There is less tolerance of potential red flags and less willingness to make trade-offs in the fit with job specifications, effectively setting a higher bar for the candidate to clear. This approach to talent evaluation, however, essentially amounts to working harder rather than smarter. There is clear room for improvement.

The second fundamental talent challenge arises from the typical trajectory of the midstream energy portfolio company. In the pre-asset phase, a group of executives with a compelling investment thesis is funded and tasked with finding, evaluating and closing deals, building partnerships, and creating a vision for the new entity. Once those pieces are in place, however, the emphasis shifts to achieving operational excellence through implementing processes, building teams, and controlling costs. But few CEOs or CFOs have the range of experience and skills to lead in both environments. Most private equity firms thus assume that finding a new CEO and CFO is an unavoidable cost of moving to the asset phase. However, this process absorbs precious time and energy, given that most private equity firms seek to exit their investments after three to five years. Obviously, there would be very real bottom-line benefits to being able to keep the same leadership team from start to finish.

How far can the candidate grow?

The key to addressing these two talent challenges—evaluating the first-time CEO or CFO and being able to choose leaders who can shift from commercial to operational environments—is understanding that they both revolve around the same set of questions:

-

How agile is the candidate?

-

How able are they to adapt to unforeseen changes?

-

Even as they are leading the transformation of their organization, what is their capacity for self-transformation?

Indeed, self-transformation seems to be a key CEO competency regardless of the leader’s level of experience in the chief executive role. In our survey of more than 400 CEOs around the world, The CEO: A Personal Reflection, 79 percent said that the CEO role required them to be able to transform themselves to meet the position’s unique responsibilities.

Several years ago, we set out to answer these questions by analyzing our database of thousands of senior executive profiles. We found that traditional competencies and experience were of little help predicting which executives were best able to adapt to new and unforeseen challenges. This is because competencies that were useful in previous circumstances may have considerably less value—and may even be counterproductive—under radically different conditions. This is particularly the case in private equity, which is often premised on a significant transformation of the enterprise.

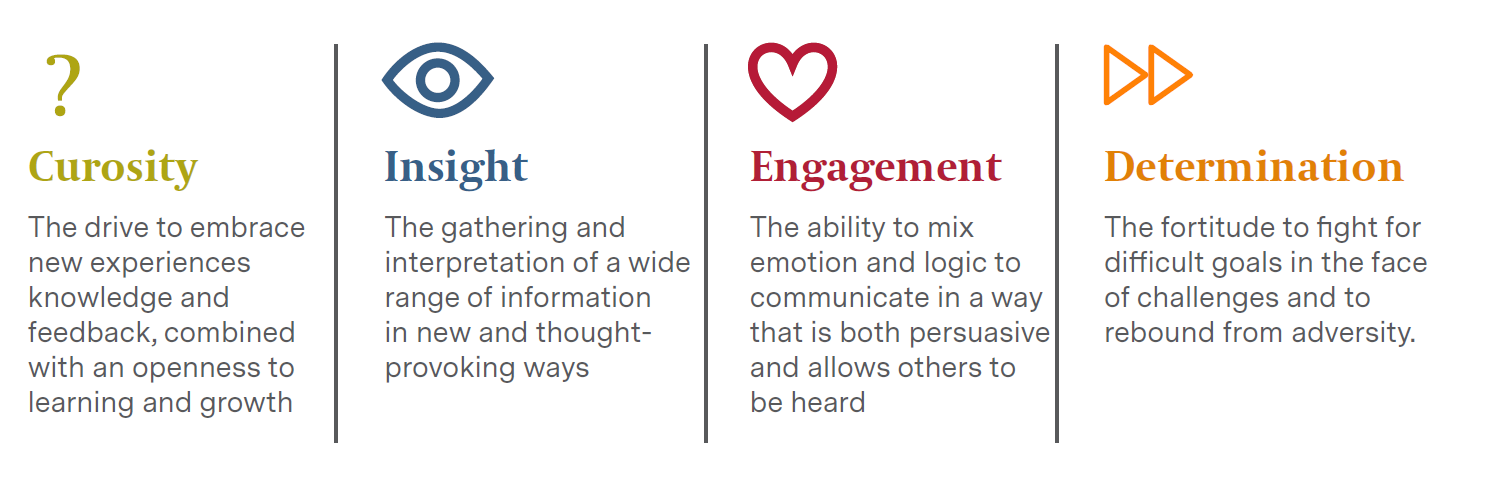

Instead, we found that executives with a high capacity for navigating change—a quality we call potential —consistently exhibited four personal qualities:

These attributes can be uncovered in structured interviews that focus on key transition points in an executive's career. Adding these findings to the traditional evaluation of a candidate's experience, competencies, and other elements results in a more complete view of the potential for professional growth.

Accelerating the growth process

A candidate who strongly exhibits the potential for self-transformation through his or her curiosity, insight, engagement, and determination is well-positioned to navigate sizable transitions—either to a first-time CEO or CFO role, or from a pre-asset, commercially-focused environment to an operational phase with an asset. But success is not guaranteed, and once the hire has been made, the private equity firm needs to continue to derisk the journey—especially since our research showed that nearly 60 percent of CEOs and CFOs in our study had not previously worked in a private equity environment. Private equity firms should thus take an active approach to the executive’s development through the following tactics:

-

Mentoring

The power of mentoring does not stop once an executive reaches the C-suite; indeed, both CEOs and CFOs can particularly benefit from having a more seasoned executive who can proactively offer advice and counsel. For the CEO, the board chair might seem like the obvious first choice, as the audit committee chair would for the CFO. But while it is important for those two pairs of executives to have strong relationships and solid communication, there is also an inescapable oversight element that may inhibit conversations that will often involve personal uncertainty and vulnerability. As a result, a different senior board member—particularly one who has held the CXO role in question may be better positioned to take on the mentoring task. -

Coaching

Unlike mentors, who provide ongoing, open-ended support, coaches are generally used to address specific development issues in a structured way. When the screening process identifies an executive who is an attractive candidate but who is susceptible to underperforming in certain circumstances, targeted coaching can be set up from day one as a preemptive measure. -

Team composition

A company’s C-suite and functional teams should operate as collective units rather than as a mere collection of individuals—allowing teams to be built with the deliberate goal of balancing each member’s strengths and weaknesses. This can be particularly effective when viewing the CEO and CFO as a pair; the midstream CEO with a strong commercial background can benefit from a CFO who has worked for companies with well-developed operations, while the operations-focused CEO will need a CFO with extensive experience in structuring deals and partnerships. Similarly, leadership roles within the finance function, like controller and treasurer, can be filled with an eye toward countering gaps in the CFO’s background.

In the world of private equity, time is of the essence. When done well, mentoring, coaching and team composition act as scaffolding rather than as a crutch, allowing the first-time CEO or CFO to grow into their roles more quickly and with greater confidence. Similarly, the right support can help the commercially-focused executive with the needed perspective and agility adapt to the different set of demands brought on in an operational environment.

Private equity firms are expert at identifying and mitigating risks in financial, operational, and market spheres. Broadening the overall derisking process to include talent management from the start is a logical extension of this inclination— and one that will pay important benefits at a time when the competition for transformative leadership has never been greater.