Not since Chinese Explorer Zheng He traveled to Southeast Asia 600 years ago has the region received as much attention from China as it is right now. Chinese businesses are aggressively expanding into the area seeking new markets and investment opportunities, ranging from mining, consumer goods, electronics, real estate to digital services. The trend is becoming so hot that that in one recent week I got three calls from Chinese VCs asking for recommendation of Fintech startups to invest in, and in another week was contacted by two Chinese Real Estate companies expressing interest to develop massive properties in Indonesia, Vietnam and even Myanmar.

China’s “One Belt, One Road” policy certainly plays a role, but even without it, the country’s eye on Southeast Asia seems inevitable. Economists have “beautiful stories” to tell about the region. I, too, once contributed to those bullish statements when working with McKinsey publishing macro reports about the region. They included information about the young population, rise of the middle class, urbanization and fast technology adaption (i.e., mobile internet). Many Southeast Asian countries seem to be more open and foreign-capital friendly than China which has shifted to local protection and control. Equally importantly, Southeast Asia’s geographical proximity to China, sizable population of overseas Chinese and emerging market status provide a sense of familiarity and comfort to Chinese businesses.

Yet, the region is harder to conquer than it seems, as many Chinese businesses have learned.

First is that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is more a political concept than one unified market.

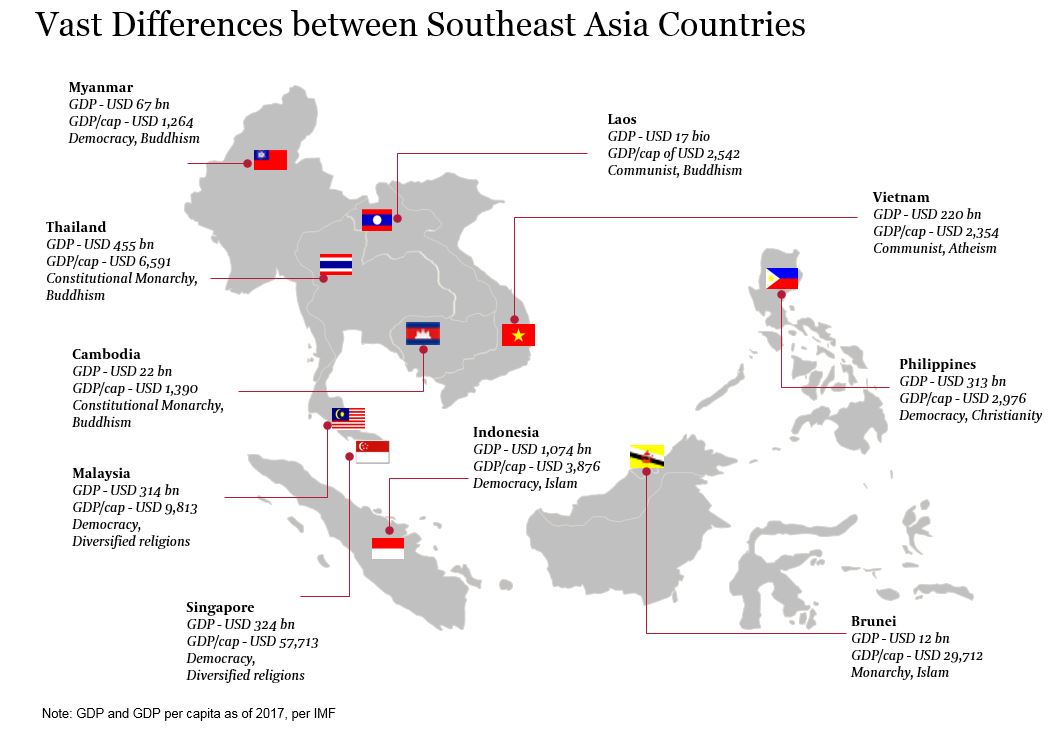

ASEAN is extremely diversified, with wealth levels ranging from the middle class (Malaysia) to impoverished (Myanmar and Vietnam); differing religions from Buddhism (Thailand) to Islam (Malaysia); and various governments from Democracies (Indonesia) to Communism (Vietnam). Even within one country, dramatic differences exist. For example, in Indonesia, there are nine sizable racial groups (all with more than five percent of the national population) living on 922 islands. This population stretches 5,120 kilometers from east to west, 1.5 times longer than the width of the United States, and similar to that of China, except that the Indonesian islands are connected by poor infrastructure, if connected at all.

What truly frustrates many Chinese businesses is that several of the managerial practices which made them successful in China may not work here.

For example:

- Aggressiveness may not pay off. Few countries globally have the kind of growth China enjoyed in the past two decades when doubling market size every three years can be a norm. In a high-growth environment, companies and individuals who aim high and take chances usually win. Look at the automobile industry. There was a time in China when as long as you got a franchise from a reputable original equipment manufacturer (OEM) to build a dealership, business would automatically come to you. Many Chinese companies are entering Southeast Asia, investing aggressively, with high targets and deep pockets. However, it may not work. I have seen companies cutting prices with little effect on increasing sales; digital giants and well-funded startups pouring millions of dollars in user acquisition but losing nearly all customers as soon as heavy subsidies stop. When the market needs a bit longer to develop, pouring financial resources alone will not get the results. It will only lead to disappointment.

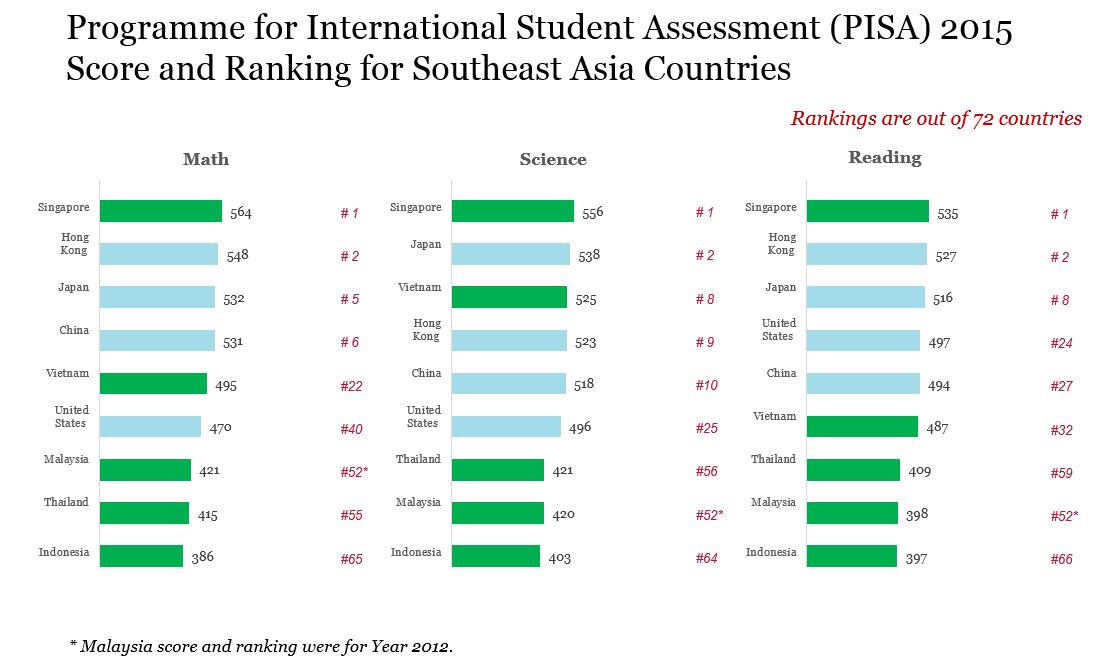

- Paying high does not always get a great team. Paying competitively is needed to attract talent. However, when the talent desired doesn’t exist, doubling the pay or giving a 100 percent bonus does not get you better results. “You cannot make the wrong people right by paying more,” as a wise colleague once said. In many Southeast Asian countries, a shortage of technical and managerial talent is very common, due to historical and educational issues. For example, the countries’ poor ranking on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) score league table accurately reflects the situation. (PISA is a global standard test that measures the math and science attainment of average students in a country. Except for Singapore and Vietnam, most Southeast Asian countries are among the bottom of the ~70 participating countries while China is always among the top).

Many Chinese companies are surprised to see the local employees much less hungry than the employees they are used to managing in China. Compared to the typical aspiring Chinese workers, in most Southeast Asian countries, people are more relaxed and content despite making less money. You can debate whether it is the influence of religion or culture, whether the attitude is good or bad, but the net effect is the same – you cannot expect to get work done faster and better just by paying more money.

- Many Chinese companies are uncomfortable managing people different from their own. When I was a strategy consultant years ago advising American, European, Japanese and Korean companies doing business in China, we often challenged them “have you localized your management team in accordance with your customer base?” Showing the pie charts of the two to highlight the gaps was one of our favorite exercises. Today, when it becomes our turn to go international, we only found our Chinese companies doing a much lesser job. Even Huawei, one of the most respected Chinese companies for its international success, often staffs its operations in a country with hundreds if not thousands of PRC Chinese, including even many of the assistants. Also, we used to laugh at the multinational corporations in China who had no choice but to limit their talent pool to English speakers and to paying a lot of money for them. Now, we see similar situations of Chinese companies coming to Southeast Asia seeking Mandarin speakers or overseas Chinese for the language and culture familiarity. Chinese companies are much less international in culture, organization and managerial practices than our products.

Yet, there is hope. We can gain confidence looking at the success stories of generations of Chinese who left China at times of war and despair and prospered elsewhere, building numerous businesses from nothing. Behind those successes, it was determination, resilience and willingness to adapt and learn. Today, we are in much better conditions with technology, capital, government support and acceptance by the locals.

However, significant changes in managerial styles are needed for Chinese businesses to be successful in Southeast Asian markets. Some practices that would work include:

- Appoint the adaptive ones. It starts when companies select internal Chinese executives to lead the expansion in Southeast Asia. When assessing internal candidates, it is important to appoint someone who is flexible, open-minded and fast in learning. When it comes to prior record, it is more important that a person has shown success and progress in diverse environments than the size of the success itself.

- Hire for fundamentals not experiences. When hiring local teams, companies will find it more beneficial to employ people based on fundamental qualities (e.g., intellect, drive, leadership capabilities) than whether they have done exactly the same job previously. Companies need to be more open-minded about the background of person as it is better to choose excellent people with little experience over mediocre people with a lot of experience. Then, companies need to be thoughtful and proactive in developing those people into the exact talent needed.

- Be the “micro-manager.” Operating in environments where capability levels are not as high as China, managers will have to be more hands-on. They often need to be very specific about what needs to be done and how to do it. They also must be rigorous in following up. The style that would be considered as non-inspirational micro-managing in markets where people are highly capable and proactive is often effective and even appreciated by employees – as they think the directions are clear and theyare helped.

- Balance between performance and community. There are many high-context countries in Southeast Asia, most notably Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines. In those countries, people build strong personal connections in the workplace. Management practices such as performance ratings, rewarding stars and weeding out low performers often backfires. Companies which do not manage the sensitivities properly end up seeing the whole team morale suffers when one team member is let go, or high performers having tremendous social pressure after being recognized with a big individual bonus. However, this does not mean that companies should give up on performance culture. They just need to execute it with more sensitivity and with a softer touch. For example, companies can adopt performance ratings but with less granularity, recognize star teams instead of star individuals or set aside some performance incentive for team events and family benefits.

- Most importantly, be patient and resilient. In any new market a company just entered, there will be a learning curve and there will be mistakes. Staying motivated and focused despite initial challenges will be critical for success. Sometimes, it will be most helpful to “forget about China”, especially “forget about how great we did in China,” as any comparison to its remarkable growth will make a Chinese company’s efforts in Southeast Asia look daunting and the prizes look small.

Yet, the opportunities are there and can be captured with patience and resilience. If you think about all those qualities, aren’t they exactly what is needed to lead any business in competitive and difficult situations? Being able to succeed in Southeast Asia may in the end be more than prospering in Southeast Asia. It can help Chinese companies to build a winning strategy that may last beyond the boom days.